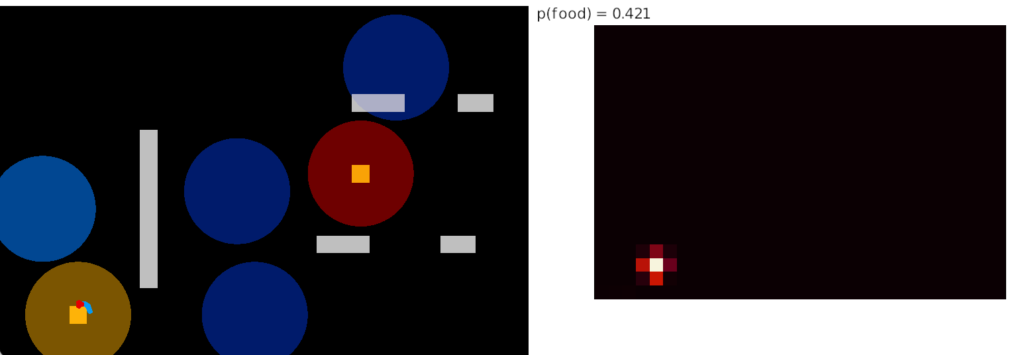

While implementing the basic model, some issues came up, including issues already solved in earlier essays.

What controls “give-up”?

The foraging task needs to give-up on a non-promising odor, ignore it, leave from the current place, and explore for a new odor. In an earlier essay, odor habituation implemented give-up. If the seek didn’t find the food within the habituation time, the sense would disappear, disabling the seek action.

The perseveration problem can be solved in many ways, including the goal give-up circuit in essay 17 and the odor habituation in an earlier essay. One approach cuts the sensor; the other disables the action. But two solutions raises the question of more possible solutions, any or all of which might affect the animal.

- Sense habituation (cutting sensor)

- Habenula give-up (inhibit action)

- Motivational state – hypothalamus hunger/satiety

- Circadian rhythm – foraging at twilight

- Global periodic reset – rest / sleep

Give-up or leave?

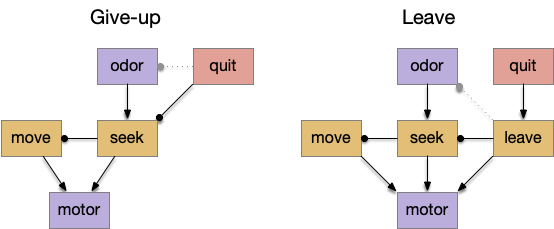

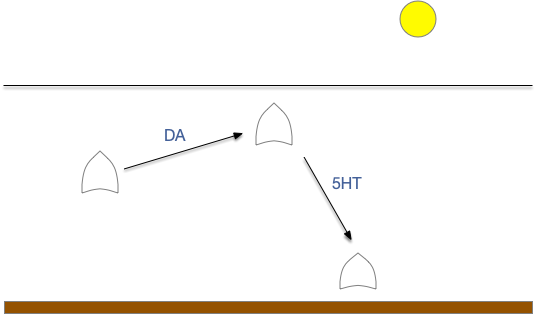

The distinction between giving-up and leaving is between abandoning the current action and switching to a new, overriding action. Although the effect is similar, the implementing circuit differs. In a leave circuit, after the give-up time, the animal would actively leave the current area (place avoidance). Assuming the leave action has a higher priority than seeking, then lateral inhibition would disable the seek action. In foraging vocabulary, does failure inhibit exploitation or does it encourage exploration?

As the diagram above shows, this distinction isn’t a semantic quibble, but represents different circuits. In the give-up circuit, the quit decision either inhibits the olfactory seek input and/or inhibits the seek action. With seek disable, the default action moves the animal away from the failed odor. In the leave circuit, the quit decision activates a leave action, which moves the animal away from the failed place, inhibiting the seek action laterally.

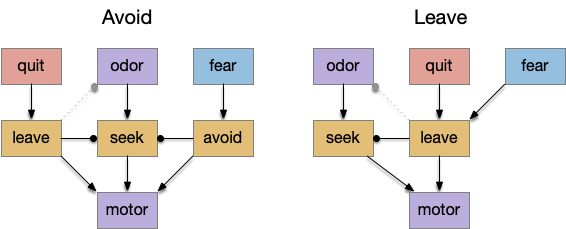

Leave or avoid?

Leaving an area is a primitive action and is a requirement for foraging. However, neuroscience papers don’t generally study foraging, they study place avoidance from aversive stimuli, which raises a question. Since the physical action of leaving and aversive place avoidance is identical, do the two actions share circuits or are they distinct?

In the avoid circuit, danger avoidance is distinct from food-seeking, only sharing at the lowest motor layers. In the leave circuit, exploration leaving and place avoidance share the same mid-locomotor action.

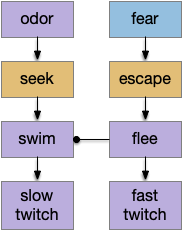

Slow and fast twitch swimming

[Lacalli 2012] explores the evolution of chordate swimming, inspired by a discovery of mid-Cambrian fossils, which suggest that fast-twitch muscles are a later addition to a more basal chordate swimming, possibly to escape from new Cambrian predators. The paper explores the non-vertebrate Amphioxus motor circuitry in like of the fossil, suggesting two distinct motor circuits: normal swimming and escape.

In this model, higher layers are independent paths that only resolve at the lowest motor command neuron level (such as B.rs). For the foraging tasks, this model that leaving an explored area would use a different system from leaving a noxious area (place aversion), despite being the same underlying motion.

Serotonin as muscle gain-control

In the zebrafish, [Wei et al. 2014] studied serotonin in V.dr (dorsal raphe) as gain-control for muscle output, amplifying the effect of glutamate signals. When they inhibited 5HT (serotonin), the muscle only produced 40% of its maximal strength. Serotonin acted as a gain-control, a multiplicative signal that amplified glutamate signals, allowing for a broader dynamic range.

[Kawashima et al. 2016] investigated 5HT in the context of task-learning for muscle effort, where 5HT caches the real-time adjustment by the cerebellum and pretectal areas. When 5HT is disabled, the real-time system still adjusts the muscle effort, but it doesn’t remember the adjustment for future bouts. That study considers the 5HT neurons as leaky integrators of motor-gated visual feedback, where zebrafish gauge the success of swimming effort by visual motion. Notably, the neurons only store visual information when the fish is actively swimming, as an action-outcome integrator.

The two studies focused on opposite muscle effects, both increasing effort and decreasing effort. 5HT can either inhibit or excite depending on the receptor type, suggesting that 5HT shouldn’t be interpreted as representing a specific value, either positive or negative, but instead possibly carrying either value.

Taking these studies as analogies, it seem reasonable to consider V.dr as an action-outcome accumulator for future effort in the 10-30 seconds range, not specific to either positive or negative amplification. Of course, because serotonin has diverse effects in multiple circuits, reality is likely more complicated.

Serotonin zooplankton dispersal and learning

Many aquatic animals have a larval zooplankton stage, where the larva disperses from its spawn point for several days or weeks, then descends to the sea floor for its adult life. A small number of serotonin neurons signal the switch to descend. Essentially, this is a single explore/exploit pair.

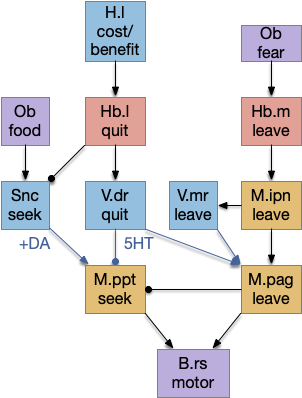

Habenula function circuit

Essay 17 is running with the model of the habenula as central to the give-up/move-on circuit. The following is a straw man model of the habenula based on the above discussion of quitting, leaving and avoiding circuits. Because essay 17 has no learning or higher areas like the striatum, the diagram ignores any learning functionality. This diagram is for a hypothetical pre-stratal habenular function.

Note, this locomotion only includes odor-based navigation. The audio-visual-touch locomotion uses a different system based on the optic tectum. This dual-locomotive system may be the result of a bilaterian chimaera brain [Tosches and Arendt 2013].

The habenula connectivity and avoidance path is loosely based on [Stephenson-Jones et al. 2012] on the lamprey habenula connectivity. The seek path is loosely based on [Derjean et al. 2010] for the zebrafish.

In this model, Hb.m (medial habenula) is primarily a danger-avoidance circuit, and M.ipn (interpeduncular nucleus) is a place avoidance locomotive region. Hb.l (lateral habenula) is a give-up circuit that both inhibits the seek function (giving up) and excites the shared leave locomotor region, implementing the foraging exploit to explore decision. Here, place avoidance and exploratory leaving are treated as equivalent. As mentioned above, this diagram is mean to be a straw man or a thought experiment, because it’s easier to work with a concrete model.

References

Derjean D, Moussaddy A, Atallah E, St-Pierre M, Auclair F, Chang S, Ren X, Zielinski B, Dubuc R. A novel neural substrate for the transformation of olfactory inputs into motor output. PLoS Biol. 2010 Dec 21

Kawashima T, Zwart MF, Yang CT, Mensh BD, Ahrens MB. The Serotonergic System Tracks the Outcomes of Actions to Mediate Short-Term Motor Learning. Cell. 2016 Nov 3

Lacalli, T. (2012). The Middle Cambrian fossil Pikaia and the evolution of chordate swimming. EvoDevo, 3(1), 1-6.

Stephenson-Jones M, Floros O, Robertson B, Grillner S. Evolutionary conservation of the habenular nuclei and their circuitry controlling the dopamine and 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HT) systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Jan 17

Tosches, Maria Antonietta, and Detlev Arendt. The bilaterian forebrain: an evolutionary chimaera. Current opinion in neurobiology 23.6 (2013): 1080-1089.

Wei, K., Glaser, J.I., Deng, L., Thompson, C.K., Stevenson, I.H., Wang, Q., Hornby, T.G., Heckman, C.J., and Kording, K.P. (2014). Serotonin affects movement gain control in the spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 34