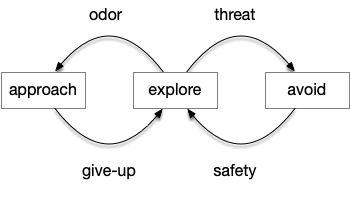

After essay 21 changed the animal’s default movement to a Lévy exploration, it’s immediate to ask whether that random search is a full action, just like a seek turn or an avoid turn. An if exploration is a controlled action, then the model needs to treat exploration as a full action, like approach or avoid.

[Cisek 2020] identifies a vertebrate system for exploration, including the hippocampus (E.hc) and its associated nuclei such as the retromammilary hypothalamus (H.rm aka supramammilary). Essay 22 considers the idea of treating the subthalamic nucleus (H.stn) as part of the exploration circuit.

Subthalamic nucleus

H.stn is a hypothalamic nucleus from the same area as H.rm, which is part of the hippocampal theta circuit, which synchronizes exploration and spatial memory and learning. However, H.stn is part of the basal ganglia and not directly connected with the exploration system.

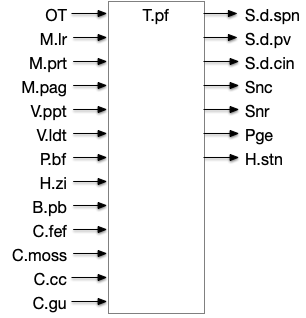

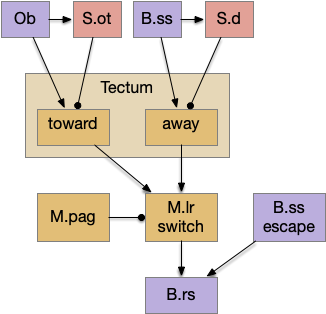

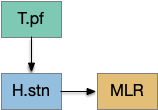

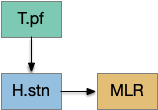

[Watson et al. 2021] finds a locomotive function of H.stn, where specific stimulation by the parafascicular thalamus (T.pf) to H.stn starts locomotion. If the stimulation is one-sided, the animal moves forward with a wide turn to the contralateral side. T.pf includes efference copies of motor actions from the MLR as well as from other midbrain actions.

For essay 22, let’s consider the H.stn locomotion as exploration. Since H.stn is part of the basal ganglia, the bulk of essay 22 is considering how exploration might fit into the proto-striatum model of essay 18.

Striatal attention and persistence

Since the current essay simulation animal is an early Cambrian proto-vertebrate, it doesn’t have a full basal ganglia. Evolutionarily, the full basal ganglia architecture could not have sprung into being fully formed; it must have developed in smaller step. Following a hypothetical evolutionary path, the essays are only implementing a simplified striatal model, adding features step-by-step. Unfortunately, because there’s no living species with a partial basal ganglia — all vertebrates have the full system — the essay’s steps are pure invention.

The initial striatum of essay 18 was a partial solution to a simulation problem: persistence. When the animal hit a wall head on, activating both touch sensors, it would choose randomly left or right, but because the simulation is real-time not turn-based, at the next tick both sensors remained active and the animal would choose randomly again, jittering at the wall until enough turns of the same direction escaped the barrier.

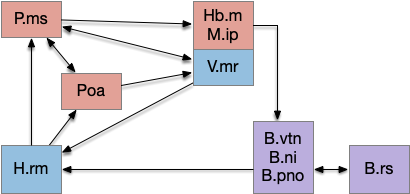

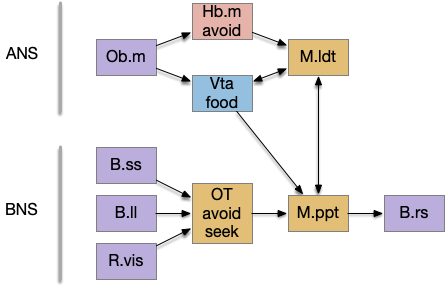

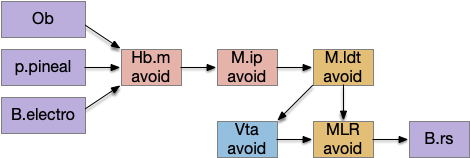

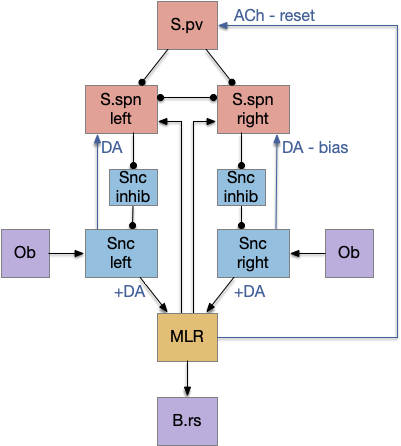

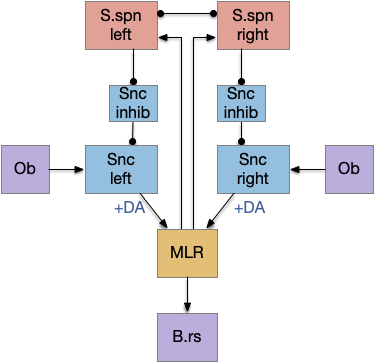

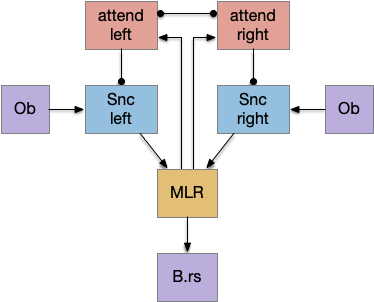

The main sense-to-action path is from the olfactory bulb (O.b) through the substantia nigra (Snc aka posterior tuberculum in zebrafish) to the midbrain locomotor region (MLR) and to the reticulospinal motor command neurons (B.rs), following the tracing and locomotive study of [Derjean et al. 2010] in zebrafish and Vta/Snc control of locomotion in [Ryczko et al. 2017]. The proto-striatum circuit is built around that olfactory-seeking circuit, acting persistent attention.

The proto-striatal model uses an efference copy of the last action from the MLR to bias the choice of the next action via a MLR to T.pf to striatum path. The model biases the choice through removing inhibition of the odor to action path. If the last action as left, the left odor is disinhibited, making it more likely to win.

The striatal system uses disinhibition for noise reasons. [Cohen et al. 2009] studied attention in the visual system and found that attention removed coherent noise by removing inhibition. By removing inhibition, the attended circuit is less affected by the controlling circuit’s noise.

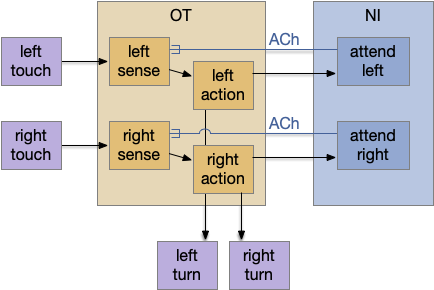

Note: essay 19 considered an alternative solution to the attention issue by following the nucleus isthmi system in zebrafish as studied in [Grubert et al. 2006], where the attention to the win-stay odor used acetylcholine (ACh) amplification to bias the choice.

Striatal columns: approach and avoid

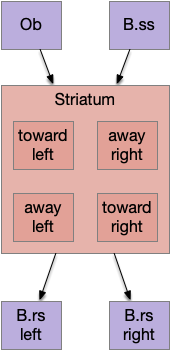

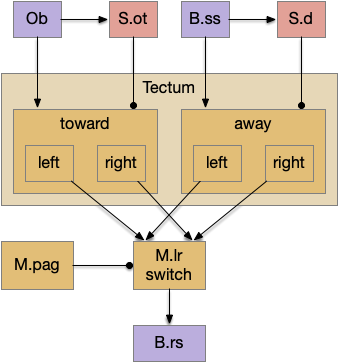

An immediate difficulty with the simple proto-striatal model is the lack of priority. Although left vs right have equal priority, avoiding a predator is more important than seeking a potential food source. Unfortunately, the proto-striatum treats all options equally. As a solution, essay 18 split the striatum into columns, where each column resolves an internal conflict without priority (“within-system”) and the columns are compared separately (“between-systems”), where “within-system” and “between-system” are from [Cisek 2019].

Subthalamic nucleus and exploration

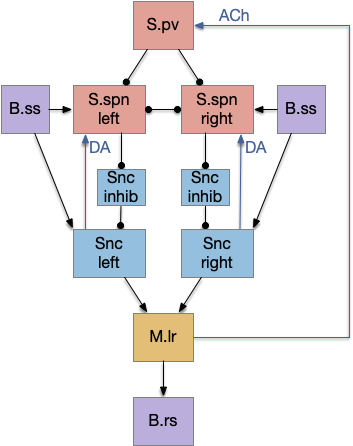

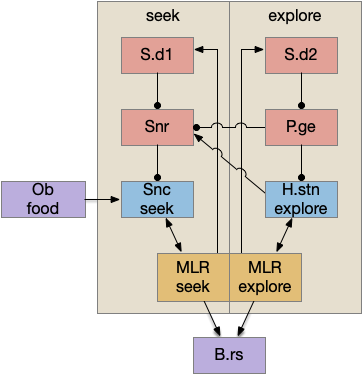

If we now treat exploration as a distinct action system, then it needs its own control system and column in the proto-striatum. The within-system choice for exploration is the left and right turns for a random walk, and the between-system choices are between the exploration system and the odor-seeking system.

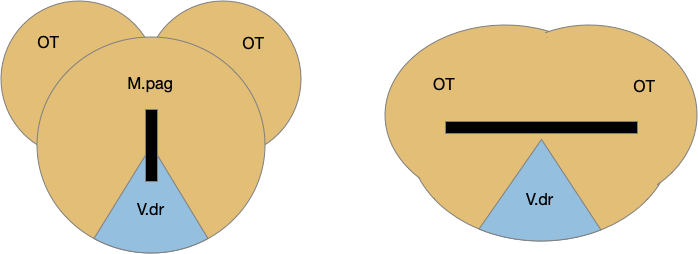

As a possible neural correlate of exploration, consider the sub thalamic nucleus (H.stn). The sub thalamic nucleus is derived from the hypothalamus, specifically from the same area as the retromammilary area (H.rm aka supramammilary), which is highly correlated with hippocamptal theta, locomotion and exploration.

[Watson et al. 2021] finds a locomotive function of H.stn, where specific stimulation by the parafascicular thalamus (T.pf) produces locomotion via the midbrain locomotive region (MLR). T.pf includes efference copies of motor actions from the MLR as well as other midbrain action efference copies. In the proto-striatum model, the feedback from MLR to striatum uses T.pf.

Seek and explore with dual striatal columns

Suppose the striatum manages both odor seeking (chemotaxis) and default exploration (Lévy walk). The two actions are conflicting with a complex priority system. When a food odor first appears, the animal should seek toward it (priority to seek), but if no food exists the animal should resume exploration (priority to explore). To resolve the between-system conflict, the two strategies need to columns with lateral inhibition to ensure that only one is selected.

Selecting the seek column enables the odor sense to MLR path, seeking the potential food odor. Selecting the explore column enables the H.stn to MLR path, randomly searching for food.

Note: the double inversion in both paths is to reduce neuron noise [Cohen et al. 2009]. Removing inhibition reduces noise, where adding excitation would add noise. In the essay stimulation, this double negation isn’t necessary.

Striatum with dopamine/habenula control

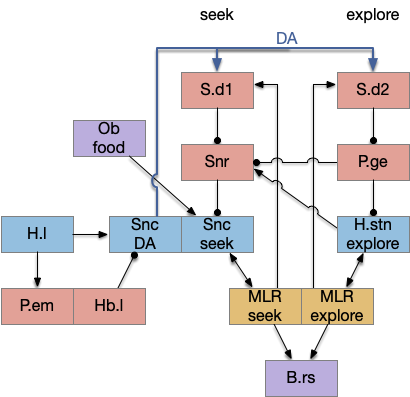

The previous dual column circuit isn’t sufficient for the problem, because it lacks a control signal to switch between exploit (seek) and explore. The striatum dopamine circuit might help this problem by bringing in the foraging implementation from essay 17.

A major problem in essay 17 was the tradeoff between persistence and perseverance in seeking an odor. Persistence ensures that seeking an odor will continue even when the intermittent. Perseverance is a failure mode where the animal never gives up, like a moth to a flame. As a model, consider using dopamine in the striatum as persistence or effort [Salamone et al. 2007], and control of dopamine by the habenula as solving perseverance with a give-up circuit.

The striatum uses two opposing dopamine receptors named D1 and D2. D1 is a stimulating modulator though a G.s protein path, and D2 is an inhibiting modulator through a G.i protein path. In the above diagram, high dopamine will activate the seek column via D1 and inhibiting the explore column via D2. Low dopamine inhibits the seek column and enables the explore column. So dopamine becomes an exploit vs explore controller.

In many primitive animals, dopamine is a food signal. In c.elegans the dopamine neuron is a food-detecting sensory neuron. In vertebrates, the hunger and food-seeking areas like the lateral hypothalamus (H.l) strongly influence midbrain dopamine neurons both directly and indirectly. Indirectly, H.l to lateral habenula (Hb.l) causes non-reward aversion [Lazaridis et al. 2019].

For the essay, I’m taking H.l as multiple roles (H.l is a composite area with at least nine sub-areas [Diaz et al. 2023]), both calculating potential reward (odor) via the H.l to Vta/Snc connection, and cost (exhaustion of seek task without success) via the H.l to Hb.l to Vta/Snc connection.

References

Cisek P. Resynthesizing behavior through phylogenetic refinement. Atten Percept Psychophys. 2019 Oct

Cisek P. Evolution of behavioural control from chordates to primates. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2022 Feb 14

Cohen MR, Maunsell JH. Attention improves performance primarily by reducing interneuronal correlations. Nat Neurosci. 2009 Dec;12(12):1594-600.

Derjean D, Moussaddy A, Atallah E, St-Pierre M, Auclair F, Chang S, Ren X, Zielinski B, Dubuc R. A novel neural substrate for the transformation of olfactory inputs into motor output. PLoS Biol. 2010 Dec 21

Diaz, C., de la Torre, M.M., Rubenstein, J.L.R. et al. Dorsoventral Arrangement of Lateral Hypothalamus Populations in the Mouse Hypothalamus: a Prosomeric Genoarchitectonic Analysis. Mol Neurobiol 60, 687–731 (2023).

Gruberg E., Dudkin E., Wang Y., Marín G., Salas C., Sentis E., Letelier J., Mpodozis J., Malpeli J., Cui H. Influencing and interpreting visual input: the role of a visual feedback system. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:10368–10371

Lazaridis I, Tzortzi O, Weglage M, Märtin A, Xuan Y, Parent M, Johansson Y, Fuzik J, Fürth D, Fenno LE, Ramakrishnan C, Silberberg G, Deisseroth K, Carlén M, Meletis K. A hypothalamus-habenula circuit controls aversion. Mol Psychiatry. 2019 Sep

Ryczko D, Grätsch S, Schläger L, Keuyalian A, Boukhatem Z, Garcia C, Auclair F, Büschges A, Dubuc R. Nigral Glutamatergic Neurons Control the Speed of Locomotion. J Neurosci. 2017 Oct 4

Salamone JD, Correa M, Nunes EJ, Randall PA, Pardo M. The behavioral pharmacology of effort-related choice behavior: dopamine, adenosine and beyond. J Exp Anal Behav. 2012 Jan

Watson GDR, Hughes RN, Petter EA, Fallon IP, Kim N, Severino FPU, Yin HH. Thalamic projections to the subthalamic nucleus contribute to movement initiation and rescue of parkinsonian symptoms. Sci Adv. 2021 Feb 5