The feeding essay introduced a number of issues both uncovered by the simulation and problems with the neuroscience. The simulation emphasized issues with the timing of the dwell state, where dwelling at the wrong time can inhibit search. Another issue as a bug was getting stuck switching states where roaming didn’t restart. The biggest neuroscience problem is a possible/likely massive misinterpretation of H.pstn (presubthalamic nucleus).

Dwell timing

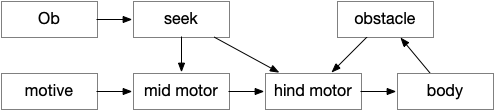

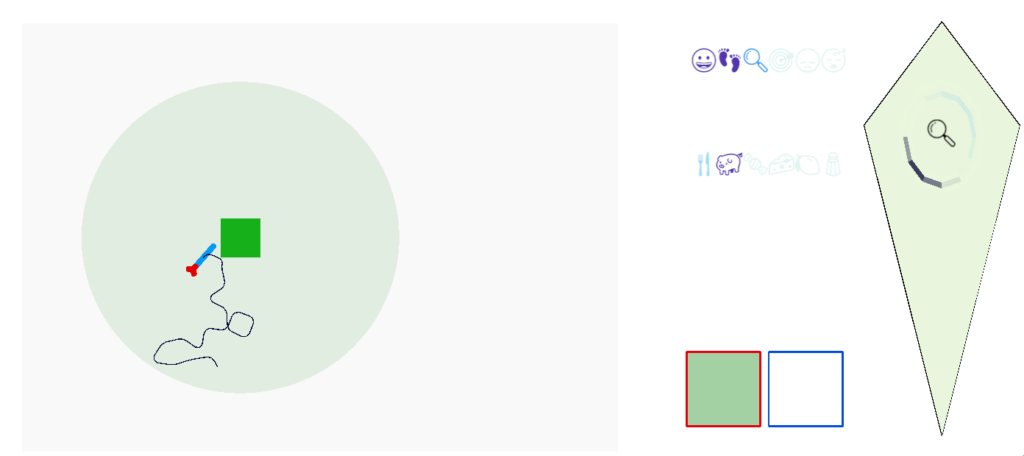

The initial trigger for a dwell state varies between species [Dorfman et al 2020]. The simulation quickly showed why. In the current simulation, since food is a single item in the center of an odor plume, dwell could either trigger on entering the odor plume or after eating food.

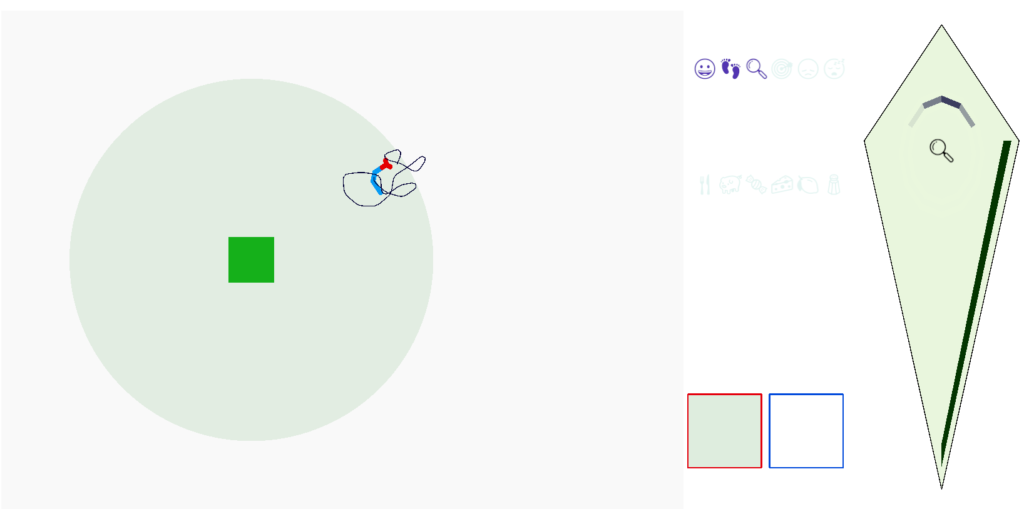

As the screenshot shows, the dwell search is counterproductive because it’s too far from the food. When dwell triggers from eating, like ladybugs eating aphids [Dorfman et al 2020], the area restricted search is more effective.

Getting stuck in a state

One programming bug happened after the animal ate, leaving the eating state, but it didn’t start the roaming state, instead remaining stuck. The roaming state didn’t recover after the eating state.

Which raises a question about a state machine model, which I’m already skeptical about as a good model of the mind. In programming, state machines can be useful because the states and transitions are enumerable, which makes them testable, because humans are good at working through lists and cases. But evolution can’t work through a list of cases, and neural circuits are not well suited to complicated mutually-exclusive state transitions.

For example, imagine a neural state machine, and consider when evolution adds a new state or a new state transition? In theory, it needs to update all the circuits for the other states to consider the new cases for the new state and new transition. Since state machines are combinatorial, each new state or transition increases complexity based on the current complexity of the state machine. Adding a state or transition to a 2-state machine is relatively simple, but adding a state or transition to a 10-state machine is much more complicated. In programming, you can work through all the new combinations and handle each case, but evolution would require new mutations for each case. It’s not impossible but becomes less likely as complexity arises.

H.pstn as misinterpreted in the essay

Essay 27 used a hypothetical H.pstn (presubthalamic nucleus) as the eating analog to H.stn (subthalamic nucleus), where each can pause actions to manage state transitions. That model treated H.pstn and H.stn as parallel modules laterally inhibiting each other. But H.pstn research has mostly found H.pstn as an inhibitory module, pausing eating for external threads or for sickness or bitterness, not as a driving force [Barbier et al 2020].

But it’s possible that H.pstn research may be preliminary, and other regions had also found negative, aversive functions to areas that later were found to have mixed function, including H.stn itself [Watson et al 2021]. Early research had assigned negative “fear”, freezing, or stopping behavior to entire regions like H.stn, M.pag.vl (periaqueductal gray, ventral-lateral), and S.a (central amygdala), but later research found a more varied behavior. These areas only appeared to be negative because a small sub-area implemented avoidance or freezing [La-Vu et al 2020]. So, it’s possible that H.pstn might have non-avoidant function, but it seems more likely that H.pstn is not an exact parallel to H.stn for eating.

H.stn is topographically ordered by motor areas and includes mouth and facial motor areas. If H.stn does perform a sustain and transition function, it might sustain and transition many/most motor areas, without a specific carve-out for feeding.

Eating-triggered dwell vs reward

A behaviorist might describe the essay, as saying that dwell is triggered by reward. I’ve been deliberately avoiding using the term reward for eating, for several reasons including those given by [Salamone and Correa 2012]. Two reasons are that the essays don’t yet have reinforcement and the meaning of “reward” is highly tied to reinforcement. A second is that reward implicitly assumes a common currency for valence, but the implementation of a common currency requires circuitry to create that currency.

Another reason raised by this essay is that eating-triggered behavior does not necessarily follow the behaviorist reward model, and specifically this essay’s eating-dependent behavior isn’t associative learning.

Suppose I use “reward-triggered dwell” instead of “eating-triggered dwell.” First, the term would be incorrect because the simulation doesn’t have an erased-source common currency “reward”. It specifically triggers from eating. Second, “reward” implies that there’s either a hedonic component (“liking”), which the simulation doesn’t have, or a motivational component, which is more complicated, because the “dwell” state is motivational.

References

Barbier, Marie, et al. A basal ganglia-like cortical–amygdalar–hypothalamic network mediates feeding behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117.27 (2020): 15967-15976.

Dorfman A, Hills TT, Scharf I. A guide to area-restricted search: a foundational foraging behaviour. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2022 Dec;97(6):2076-2089.

La-Vu MQ, Sethi E, Maesta-Pereira S, Schuette PJ, Tobias BC, Reis FMCV, Wang W, Torossian A, Bishop A, Leonard SJ, Lin L, Cahill CM, Adhikari A. Sparse genetically defined neurons refine the canonical role of periaqueductal gray columnar organization. Elife. 2022 Jun 8;11:e77115.

Salamone JD, Correa M. The mysterious motivational functions of mesolimbic dopamine. Neuron. 2012 Nov 8;76(3):470-85.

Watson GDR, Hughes RN, Petter EA, Fallon IP, Kim N, Severino FPU, Yin HH. Thalamic projections to the subthalamic nucleus contribute to movement initiation and rescue of parkinsonian symptoms. Sci Adv. 2021 Feb 5