A problem with essay 17 was the lack of action stickiness, which became a problem for avoiding obstacles. When the animal hits an obstacle head-on, both touch sensors fire and the animal chooses a direction randomly. Because the decision repeats every tick (30ms) and chooses randomly to break ties, the animal flutters between both choices and remains stuck until enough random choices are in the same direction to escape the obstacle. What’s needed is a stick choice system to keep a direction once it’s selected. In some decision studies, this is a “win-stay” capability.

A previous essay solved this issue with muscle-based timing or a dopamine-based system, but some of the theories of the striatum function suggest it might solve the problem. The core idea uses the dopamine as a feedback enhancer to sway choice to “stay.”

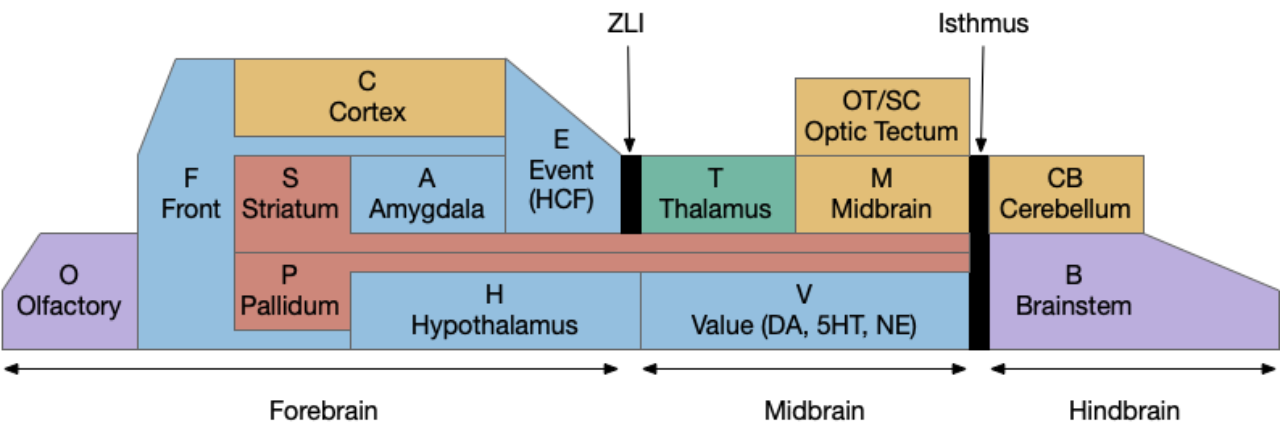

The circuit is intended not as the full vertebrate basal ganglia, but a possible core function for a pre-vertebrate animal in the early Cambrian. The circuit here represents only the direct path and specifically only the striostome (patch) circuit, and only represents the downstream connections, and ignores the efferent copy and upstream enhancements. Despite being simplified, I think it’s still to complicated as a single evolutionary step.

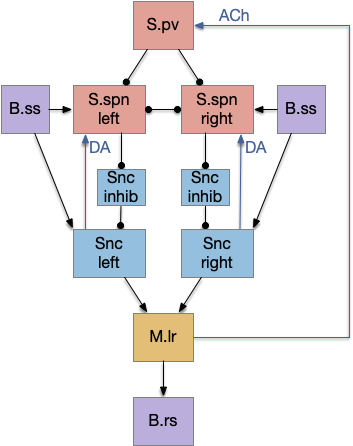

Simplified proto-circuit

If that simplified striatal circuit is too complicated for an evolutionary step, but lateral inhibition is a reasonable circuit.

The above simplified circuit is a simple lateral inhibition circuit with an added reset function from the motor region.

The main path is through the somatosensory touch (B.ss), through the substantia nigra pars compacta (Snc – posterior tubuculum in zebrafish) to the midbrain locomotive region (M.lr). [Derjean et al. 2010] traced a similar path for olfactory information. I’m just replacing odor with touch.

The reset function might be a simple efferent copy from the central pattern generator for timing. In a swimming animal like an eel, the spinal cord controls the oscillation of body undulation, moving the animal forward. Because the cycle is periodic, when the motor system fires at a specific phase such as an initial-segment muscle twitch, it can send a copy of the motor signal upstream as an efferent copy. That signal is periodic, clock-like, something like the theta oscillation in vertebrates, and upper layers can use that clock.

Zebrafish larva swim in discrete bouts, each on the order of 500ms to 2sec. Since the specific mechanism that organizes bouts isn’t known, any model is just a guess, but might motivate some of the striatal circuitry. Specifically, the acetylcholine (ACh) path in the striatum. The motor swimming clock could break movement into bouts with a reset signal.

Since the sense to Snc to M.lr is a known circuit [Derjean et al. 2010], lateral inhibition is a common circuit, and motor efferent copy of central pattern oscillation is also common, this simplified circuit seems like a plausible evolutionary step.

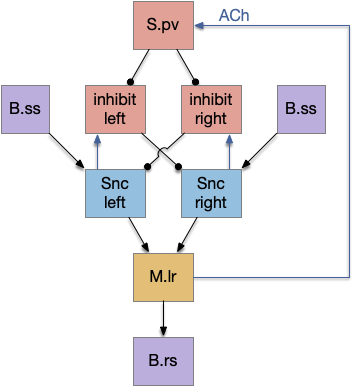

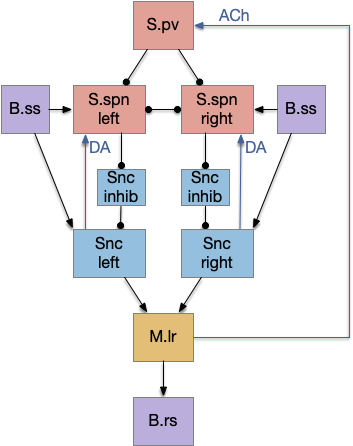

Improved circuit

Some problems in the simplified circuit lead to improvements in the full circuit. The simplified circuit is susceptible to noise, leading to twitchy behavior, because sensors and nerves are noisy. Secondly, when two options compete, a weaker signal might win the competition if it arrives first. An accumulator system that averages the signals will give better comparisons.

To improve the decisions, the new circuit adds a single pair of inhibition neurons, specializes the existing neurons, and changes the connections.

To improve decision making, the S.spn neurons are now accumulators, averaging inputs over 100ms or so, just long enough to reduce noise without harming response time too much. As an implementation detail, the S.spn neurons might either accumulate calcium (Ca) itself, or a partner astrocyte might accumulate Ca.

To improve noise behavior, the added Snc inhibition neurons tonically inhibit the Snc neurons, so a stray signal from B.ss to Snc won’t inadvertently trigger the action before the decision. The dual inhibition is a slightly complicated circuit which reduces noise because an active path (disinhibited) has only sense inputs; the modulatory signals are taken away.

The dopamine feedback has the benefit of being a modulator instead of a pure feedback signal. Because it’s a multiplicative modulator, dopamine doesn’t trigger the cycle itself. When the signal ends, the dopamine feedback doesn’t continue a ghost reverberation signal.

Choice decisions: drift diffusion

Psychologists, economists, and neuroscientists have several useful models for decision making, primarily deriving from the drift diffusion model [Ratcliff and McKoon 2008], which extends a random walk model to decision-making. While most of the research appears to be centered on visual choice in the cortical (C) visual system, such as the lateral intraparietal area (C.lip), the concepts are general and the circuits simple, which could apply to many neural circuits, even outside of the mammalian cortex.

Drift-diffusion is a variation of a random walk. Each new datum adds a vector to an accumulator, walking a step, until the result crosses a threshold.

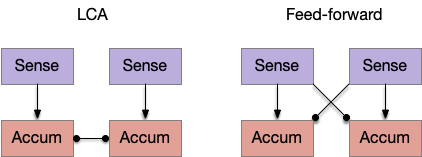

One simple model is the leaky competing accumulator (LCA) of [Usher and McClelland 2001], where each choice has an accumulator, and the accumulators inhibit each other laterally. Another model use feedforward inhibition instead of lateral inhibition, where each sense inhibits its competitors. For this essay, these models seem a good, simple options for the simulation.

In the context of the striatum, [Bogacz and Gurney 2007] analyze the basal ganglia and cortex as a choice-based decision system. They interpret the direct path (S.d1) as the primary accumulator, and the indirect path (S.d2 / P.ge / H.stn) as feed-forward inhibition. They suggest that the basal ganglia could produce near-optimal decision in the two-choice task.

References

Bogacz R, Gurney K. The basal ganglia and cortex implement optimal decision making between alternative actions. Neural Comput. 2007;19:442–477

Derjean D, Moussaddy A, Atallah E, St-Pierre M, Auclair F, Chang S, Ren X, Zielinski B, Dubuc R. A novel neural substrate for the transformation of olfactory inputs into motor output. PLoS Biol. 2010 Dec 21

Ratcliff, R., & Childers, R. (2015). Individual differences and fitting methods for the two-choice diffusion model of decision making. Decision, 2(4), 237.

Usher, M., & McClelland, J. L. (2001). On the time course of perceptual choice: The leaky competing accumulator model. Psychological Review, 108, 550–592.

Wang, X.-J. (2002). Probabilistic decision making by slow reverberation in cortical circuits. Neuron, 36, 1–20.