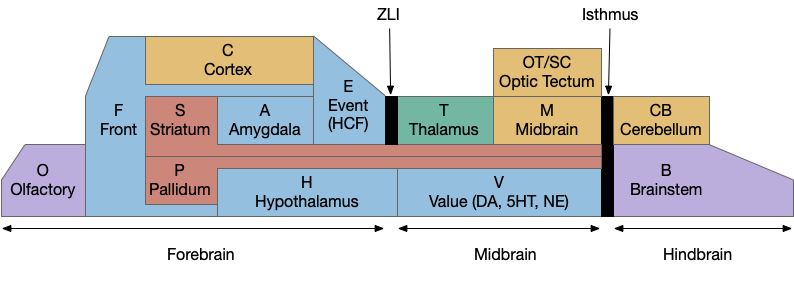

Because learning and remembering the vast number of vertebrate brain nuclei and areas and connections is a daunting task, I’ve needed to use a simplified mnemonic model to make some sense of the whole and show how individual pieces with together. The following is a simplified model of the brain, emphasizing subcortical areas, and with distinct initial letters so a quick scan of an abbreviation is pre-categorized in its general location.

Disclaimer: this is a personal model and may not accurately reflect any current consensus of neuroscience. Specifically, the abbreviations are different from the common neuroscience appreciations.

A key decision of the model is to use consistent single-letter prefixes. Some of these letters are clear, like “H” for hypothalamus, “A” for amygdala, and “T” for thalamus, but others are a bigger stretch. The “V” for monoamines (dopamine, serotonin, norepineprine) and acetylcholine (ACh) is meant to indicate “value” reflecting their roles in providing operating current values. The hippocampal formation, which is a center of episodic memory, uses “E” for event or episodic because “H” for hypothalamus is already taken.

Not every area fits cleanly in a box, partly because evolution fails to follow clear, human-friendly boundaries. But also because several areas are intrinsically liminal: their function depends on manipulating data from multiple areas. For example, the cingulate cortex (C.cc or F.ac), which has functions related to attention and conflict detection, is often placed with the frontal area as part of the prefrontal cortex (PFC, or F.pfc), but also ranges along the cortex to the hippocampus. The zona incerta (H.zi), which is also attention-related, is strongly related to the midbrain motor areas and the optic tectum, despite being physically adjacent to, or possibly part of the hypothalamus. The pre optic areas (P.poa or H.poa), which are related to exploration, reproductive behavior, and aggression, have traditionally been grouped with the hypothalamus (H), but more recently grouped with pallidal (P) areas.

The bilaterian chimeral brain (“H” and “OT”)

The bilaterian chimeral forebrain theory [Tosches and Arendt, 2013] is an interesting organizational principle that the mnemonic model uses to place the hypothalamus (H) firmly in the forebrain as a central organizing pole and the midbrain motor areas centered around the optic tectum/superior colliculus (OT). The coloring scheme of blue and brown is meant to group areas with their primary pole, motivational and limit areas with the hypothalamus and motor and habit cortex with the midbrain and optic tectum.

The chimeral model itself suggests that the bilaterian brain, including insects and vertebrates, is derived from two ancestral sources, the forebrain from the larval apical tuft and the midbrain/hindbrain from the adult motor areas. Larvae from mollusks and annelids still show the ancestral apical areas. The apical tuft is a chemosensory area that communicates using broadcast neuropeptides, while the bilaterian motor areas use connected neurons and neurotransmitters. The hypothalamus with its melange of over 100 neuropeptides, internal chemical sensing, and connections with visceral and olfactory areas is a descendent of the apical tuft. Contrariwise, the central pattern generators of the spinal cord, hindbrain and midbrain would be descendants of the adult motor areas.

The diencephalon and prosomeric model (“H” and “T”)

The mnemonic model groups everything between the zona limitans intrathalamica (ZLI) and the isthmus organizer into the midbrain and everything rostral to it into the forebrain, including the hypothalamus, the zona incerta (H.zi) and the pre-thalamic eminence (P.em), while leaving the thalamic reticular nucleus (T.r) with the thalamus, but that entire region is currently under debate by neuroscientists (and the model doesn’t reflect any of the theories directly.)

The diencephalon is an older anatomical term that groups the pre-tectal areas (M.pt), the thalamus (T), the hypothalamus (H) and the zone between H and T (the “pre-thalamus”) into a single region. The diversity of function and of developmental gene expression have raised the question of the usefulness of that grouping, in particular putting the hypothalamus and thalamus into a shared group.

The prosomeric model [Puelles and Rubinstein, 1993] instead splits the hypothalamus and thalamus into two regions made of five sub-regions, p1-p3 representing the pre-tectal, thalamic, pre-thalamic areas, and hy1 and hy2 representing two regions of the hypothalamus. p3 includes interesting liminal areas zona incerta (H.zi), pre-thalamic eminence (P.em), and T.r.

But critics of the prosomeric model like [Bedont, 2015] have argued that some areas of the pre-thalamus (prosomeric p3) are closely genetically and developmentally tied with the hypothalamus, not the thalamus, questioning whether prosomere is a useful organizing principle.

That area of the brain has an unusual genetic and chemical marker at the ZLI, where the Shh gene expression rises from its usual basal location to the top of the embryo, creating a thin chemical boundary between the thalamus and pre-thalamus [Kiecker and Lumsden, 2004]. The ZLI splits both the diencephalon model and the prosomeric model in two.

For simplicity, the mnemonic model uses ZLI as a dividing line and since the model is not detailed enough to give p3 its own box, it can remain neutral on the neuroscience debate, although it does follow the prosomeric model enough to strongly split the hypothalamus from the thalamus and also put H with the forebrain.

Striatum and pallidum (“S” and “P”)

All areas with striatal or pallidal structure are grouped together, essentially everything in the sub-pallium derived from the median ganglionic eminence (MGE) and lateral ganglionic eminence (LGE), following the model of [Swanson 2000.]

The stratum and pallidum (S/P, basal ganglia or sub-pallium) are interested because they’re key components of conditioned stimuli, conditioned responses, conditioned values, reinforcement learning, feedbacks loop in the cortex, and communication between the cortex and the midbrain motor areas (M and OT) and motivational areas (H and V) as well as combining episodic context (E.hc, hippocampus) and motivational context (A, amygdala). As well as communicating between areas, the striatum (S/P) is a key component of communication within the cortex and frontal areas with cortical intratelencephalic neurons (IT, C.5a) strongly connecting to the striatum.

The grand simplification lumps many areas into one naming group. In the traditional striatum, the caudate and putamen becomes S.cp (or. S.d for dorsal striatum). The nucleus accumbens becomes S.v or S.nac, and if greater detail is needed, medial shell (S.msh) and core (S.core).

The traditional pallidum becomes P.ge and P.gi for internal and external globus pallidus, but can be more specific for the habenular-projecting neurons (P.h), and the endopeduncular nucleus, which is a habenular-projecting area for mice becomes (P.epn). The ventral pallidum is P.v (or P.si if the distinction is needed.)

Since the septum also derives primarily from subpallial sources, it becomes S.e and P.e (S/P related to “E” hippocampus) or S.ls and P.ms for lateral and medial septum (as well as P.ts, P.sf, and P.bac for posterior septum and P.db or P.msdb for the diagonal band.)

Since the extended amygdala includes striatal and pallidal components, becomes S.a and P.a for the amygdala S/P (or S.cea, P.bst for central amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminals.)

If the pre-optic areas (H.poa) are instead grouped with the pallidum, they become P.poa (or more specifically P.mpo, P.lpo.)

And, since the pre-thalamic eminence is the major source for pallidal cells projecting to the habenula (P.h to Hb), it receives an honorary P.em despite not technically belonging to the telencephalon.

In theory, following the mnemonic model would put the output of the basal ganglia as M.snr and V.snc because the substantia nigra pars reticulara is both in the midbrain motor area (M) and projects to it and the substantia nigra pars compacta is part of the dopamine circuit in the V area, but the initial S gives a natural give S.nr and S.nc.

If there is anyone who has read all through that list, I hope there’s some understanding of why it’s useful to initially lump all the above into S and P groups in the process of learning all the names.

Hippocampal formation (“E”)

Although the initial letter “E” is the least effective, grouping hippocampal formation areas is helpful despite the problems. The hippocampus itself becomes E.hc, dentate gyrus E.dg, ca1 is E.ca1, the subiculum is E.sub, the lateral and medial entorhinal cortices become E.lec and E.mec, and the prerhinal and parahippocampal are E.pr and E.phc (or E.por for the equivalent postrhinal cortex in rodents.)

Thalamus (collo- and lemno-)

One interesting division in the thalamus that the model does not portray is the [Butler 2008] distinction between collothalamic and lemnothalamic areas, where “collo” refers to the superior and inferior colliculi, essentially the optic tectal (OT) area, and “lemno” are direct sensory inputs that bypass the midbrain. The collo- and lemno- receiving areas appear to be evolutionary distinct with unique functions. For example, the extrastriatal visual cortex is a lemno- receiving area, processing visual data from the OT. But because the thalamus also includes areas for the cortex to talk to itself (T.a from the hippocampus to the cortex, T.md for input to the frontal (F) areas, T.re for frontal to hippocampal, T.va and T.vl for internal motor planning), as well as a distinction between direct signal information (“core”) and diffuse context data (“matrix”), it may be best that the model doesn’t try to overcomplicate all those differences.

Frontal and Cortical (“F” and “C”)

The idea between splitting the cortex into frontal and cortical is due to the different connectivity. The frontal areas (F) are more strongly connected with the hypothalamus (H) and its areas, while the other cortical areas (C) either directly control midbrain motor (M) or provide context to areas like the optic tectum (OT).

So, the ventral-medial prefrontal cortex (F.vm) is in the frontal area, as well as the orbital-frontal (F.ofc) and possibly the insular and parts of the cingulate cortex (F.ai, F.i, F.ac), but the dividing lines don’t appear to be particularly clear-cut. The dorsal-lateral PFC (F.dl) seems to be motor based, but “C.dl” makes no sense.

Because it’s the primary olfactory cortex, the piriform is O.pir.

The mnemonic model has been a personal help also in trying to understand the connectivity of regions. As well as grouping similar inputs and outputs (for example areas that project too many hypothalamic nuclei: H.vm, H.dm, H.l, H.pm, etc.), the naming also helps distinguish areas that stand out. For example, areas that come directly from the hindbrain/brainstem like B.pb (parabrachial nucleus) are interesting inputs to areas like the amygdala that mostly receive indirect input. And output areas that project to brainstem areas (B.ret to use the archaic, lazy reticular instead of specific B.xx areas) stand out as actual motor outputs instead of endless internal processing.

References

Bedont, Joseph L., Elizabeth A. Newman, and Seth Blackshaw. “Patterning, specification, and differentiation in the developing hypothalamus.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Developmental Biology 4.5 (2015): 445-468.

Butler, Ann. (2008). Evolution of the thalamus: A morphological and functional review. Thalamus & Related Systems. 4. 35 – 58. 10.1017/S1472928808000356.

Kiecker C, Lumsden A. Hedgehog signaling from the ZLI regulates diencephalic regional identity. Nat Neurosci. 2004 Nov;7(11):1242-9. doi: 10.1038/nn1338. Epub 2004 Oct 24. PMID: 15494730.

Puelles, Luis, and John LR Rubenstein. “Expression patterns of homeobox and other putative regulatory genes in the embryonic mouse forebrain suggest a neuromeric organization.” Trends in neurosciences 16.11 (1993): 472-479

Swanson LW. Cerebral hemisphere regulation of motivated behavior. Brain Res. 2000 Dec 15;886(1-2):113-164. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02905-x. PMID: 11119693.

Tosches, Maria Antonietta, and Detlev Arendt. “The bilaterian forebrain: an evolutionary chimaera.” Current opinion in neurobiology 23.6 (2013): 1080-1089.