Unsurprisingly since essay 26 was a first cut at selective attention, it exposed a number of problems with both the neuroscience and the simulation model itself.

Specific give up

The current give up circuit is a global circuit, which doesn’t depend on the current stimulus. For this essay, the animal has two potential and because the give up is global, when the animal gives up, it gives up on both odors.

An improvement would be a cue-specific give up capability. When the animal gives up on odor A, it should investigate odor B. Instead it gives up on both. I need to add some mechanism to create a cue-specific give up capability.

As a possible neural analog, the adenosine receptor can work as a local give-up circuit by integrating neural activity. Since adenosine is essentially a waste produce from neural activity, long activity will accumulate adenosine. The A1 adenosine receptor detects the adenosine and inhibits activity, since it’s a Gi receptor.

Olfactory complexity and attention

The essay’s odor model is extremely oversimplified, because odor receptors are feature detectors, not molecule receptors, and odors are combinations of molecules. Since a specific odor is a combination of features, P.bf (basal forebrain) can’t be a simple winner-take-all inhibitory circuit as implemented in this essay. Instead, attention needs to be a set of features that excludes the distractor odor’s features.

Olfactory gamma and beta

Although the essay treats the olfactory bulb data as direct signals, oscillations are a major feature of the olfactory bulb. Strong odors trigger gamma (40-100Hz) signals in Omt (mitral/tufted output cells), enhanced by ACh (acetylcholine) from P.bf. Feedback from O.pir (olfactory piriform cortex) triggers beta (15-30Hz) oscillations. In addition, interactions with breathing in mammals synchronized with theta (4-10Hz). Although, in the last case, since the simulation animal is aquatic, breathing isn’t an appropriate synchronizer.

Temporal gradient seek issues

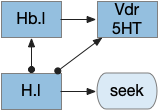

Odor seeking in essay 26 uses temporal gradient descent modulated by head direction in Hb.m (medial habenula) and B.ip (interpeduncular nucleus). The animal combines its head direction with the temporal gradient to estimate the odor direction, and it saves the result as a goal vector. As the animal turns, it can improve the direct estimate. In the phototaxis example of essay 25, the saved goal vector direction helped with intermittent data, where it could remember the light location for a few seconds.

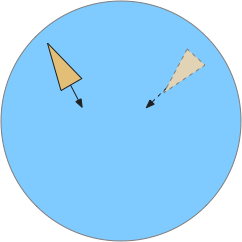

However, the system as implemented in the model is extremely limited. It can’t truly triangulate to locate the odor, but can only improve the single direction. In the diagram above, the animal can only select one of the two vectors as an estimate. It can’t combine the two into a better estimate of the center. Also, in the diagram, the earlier estimate is no longer useful because the animal has moved.

Now, the issue might be purely in the simulation. If B.ip and Vdr (dorsal raphe serotonin) are calculating this kind of estimate, it’s likely their computation is better than the current simulation.

The selection is a trade off where a stronger gradient is likely a better estimate, but if the animal moves too far from the earlier sample, the old direction is no longer relevant. Since the animal lacks the sophistication of an allocentric map to resolve the discrepancy, it discards the old value.

The current implementation decays the old estimate to allow newer estimates to overwrite it even if the later gradient is weaker. Essentially the memory is like a leaky integrator, as is appropriate for placing it in the serotonin neurons and/or associate glia with short term (5s) memory as in simple zebrafish motor memory [Dragomir et al 2020].

Bayesian updates

In a future essay, it might be interesting to explore this issue to see if a simple Bayesian system could be implemented in low-complexity circuits, where stronger data would update the current model more than the current model.

Self motion and gradient vectors

When the animal is turning, the running average no longer represents a straight line. For the gradient vector, the system assumes the recent average was measured along the current head direction, but turns violate this assumption. To avoid miscalculating gradient vectors, the animal should suppress measurement during turns.

Swimming and theta

The gradient seek issues above are compounded with swimming with a fixed head. Early vertebrates would have had a fixed head like sharks, meaning that each swimming stroke would move the head from side to side. That sideways movement would affect the odor gradient and head direction.

A simplistic fix would take an odor gradient sample only on each swim stroke, only reporting at the stroke end for consistency and to average from the beginning of the stroke to the end. That solution would give a consistent measurement in a reasonably consistent direction, as opposed to sampling randomly in a cycle.

Log encoding vs linear encoding

For simplicity, I’e used linear encoding for signals in the essays, because the basic functional architecture remains the same, and the simulation isn’t precise enough to need more complexity. But for odors, the dynamic range between a single molecule detection and an overpowering odor doesn’t scale well with a linear representation.

In particular, the odor weight from the simple distance gradient, together with above mentioned temporal gradient issues might be better modeled with a log signal. Basically, the issue I raised above with gradient vector sampling might be more tractable with a different encoding, and log encoding might make the actual neural circuit less finicky than the current linear model.

Seek mode switching

The essay’s simulation lacks a specific mode switching circuit. In vertebrates the peptide core (hypothalamus, PAG, B.pb area) switches action modes from roaming to seek to eating to rest and sleep. These modes are motivated and depend on internal needs and scheduling impulses programmed by evolution.

References

Dragomir EI, Štih V, Portugues R. Evidence accumulation during a sensorimotor decision task revealed by whole-brain imaging. Nat Neurosci. 2020 Jan;23(1):85-93.