I’m considering exploring Braitenberg’s vehicles [Braitenberg 1984] for essay 14 in combination with the ideas from the archaoslug. The vehicles are a simple almost trivial design with surprisingly useful behavior. Each vehicle has a combination of sensor-motor pairs, taking advantage of the physical layout for the motor and sensor behavior.

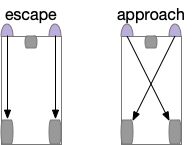

Here, the sensors detect light and directly drive the motor wheels. Vehicles with crossed signals approach the light, while vehicles with uncrossed signals avoid the light. Braitenberg also explores negative signals where the signals inhibit the motors, and additional signal-motor pairs for different senses. The value of the Braitenberg vehicles is showing how simple control circuits can form the basics of behavior.

Optic tectum as an example

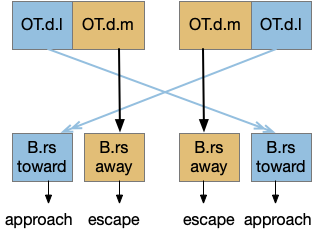

The optic tectum uses this dual-circuit architecture for approach and escape [Isa 2021]. The optic tectum is a midbrain optical and motor area responsible for much of vision in non-mammalian vertebrates and an understudied component of mammalian vision. In the OT, escape signals connect to ipsilateral (same side) motor neurons, and approach signals connect to a different set of motor neurons but crossing sides.

In the diagram, B.rs are reticulospinal motor neurons in the brainstem. OT.d.m is the medial optic tectum in the deep layers, and OT.d.l is the corresponding lateral. The OT shallow layers process optical information, and the deep layers drive motor actions. Stimulating the medial OT makes the animal escape and stimulating the lateral OT encourages approach. As a mnemonic, since approaching needs to aim at the target, its sensors need to be spread out (lateral), but escaping needs less precision and can rely on closer or merged (medial) sensors.

Because the Braitenberg architecture is so simple, I think it’s reasonable to imaging that primitive animals would quickly develop a similar pair of crossed and uncrossed systems as soon as neurons with specific connectivity were available, after the initial broadcast repeater nerved nets like in sea anemones (cnidaria). The dual systems mirrors the dual chemosensory and mechanosensory cell families in the archaoslug, which might have also encouraged split control.

Essay 14 pre-design

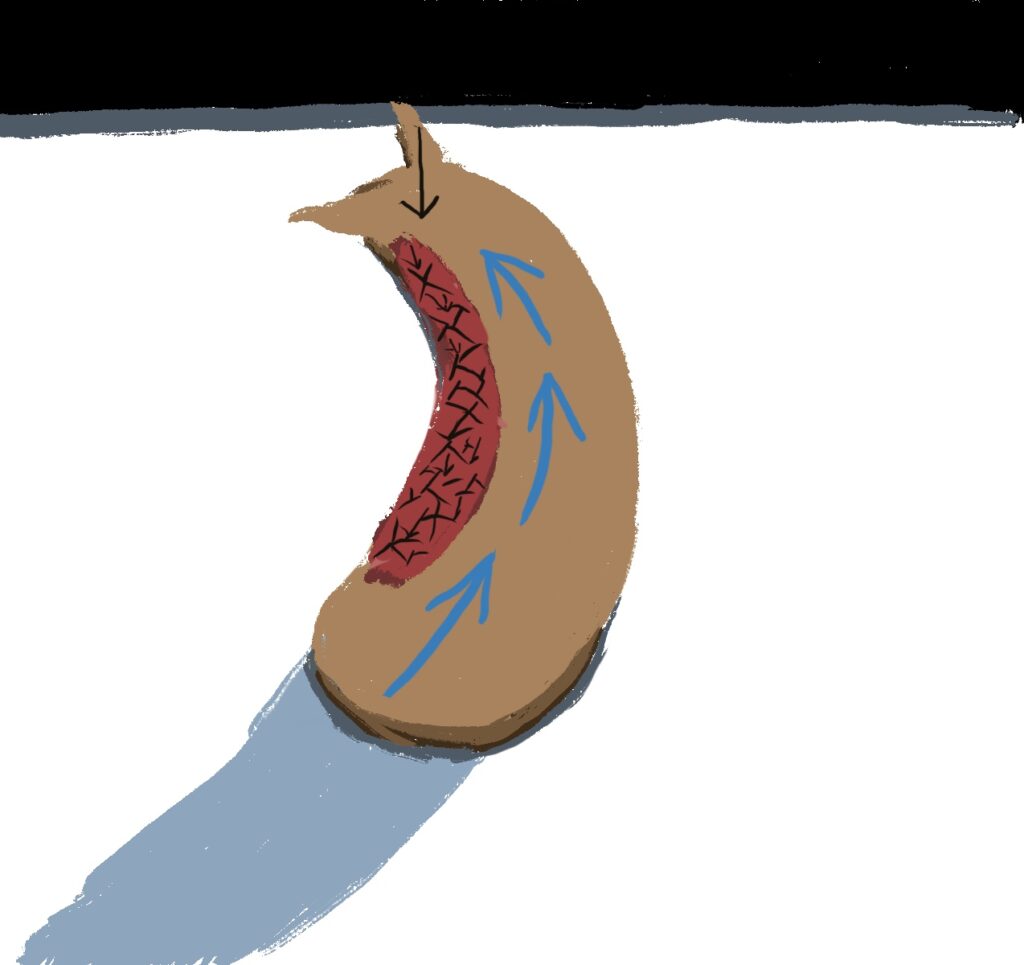

As a bilateral enhancement to the amoeboid archaoslug, I’m thinking of trying a ciliomotor slug with primitive obstacle avoidance but without any directed approach. Avoidance is a smaller evolutionary step because it can reuse the mechanosensory and nerve nets of the archaoslug, only adding a single crossed-pair of long-range neurons. After hitting an obstacle, muscle contractions turn the animal away from the obstacle.

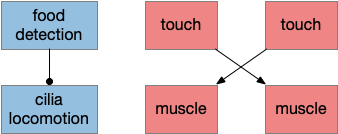

The mucociliary sole remains the main locomotion and food detection. The slug still searches for food by grazing randomly on algae or bacterial mats, relying on browning motion to find food. There’s no tracking or approach system.

As mentioned above, the control systems for grazing locomotion and for obstacle avoidance are independent. Cilia locomotion is automatic with no neural control until the slug detects that it’s above food, when it stops. The locomotion direction is semi-random.

If the slug hits a wall, it contracts the side opposite the touch. This circuit is flipped from the Braitenberg vehicle, which has uncrossed signals for avoidance. The touch sensor activates the contralateral nerve net to contract the side muscle, and the slug turns toward the contracted side, away from the obstacle.

On motivation

Even in this trivial example, I think it’s useful to consider motivation in contrast with stimulus/response behavior. Since the basis of the word motivation is “to move,” it’s reasonable to use motivation as meaning moving force. So, motivation is a source of action without needing external stimulus. In the Braitenberg slug, the motivation is in the mucociliary sole itself, because it moves without external stimulus. If so, the motivation isn’t even neural; it’s just started by evolution.

The distinction of motivated vs non-motivated action is important in understanding the system. Knowing the sources of intrinsic motivation allows for tracing action from the source to its final result. As a design principle, adding self-motivation is more stable, because the animal is less likely to get stuck waiting for external stimuli to get started.

References

Braitenberg, V. (1984). Vehicles: Experiments in synthetic psychology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. “Vehicles – the MIT Press”

Isa, Tadashi, et al. “The tectum/superior colliculus as the vertebrate solution for spatial sensory integration and action.” Current Biology 31.11 (2021): R741-R762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.04.001