Essay 16 extends the odor seeking (chemotaxis) of essay 15 by adding a single memory item. The memory caches a failed odor search, avoiding the cost of searching for false odors. The neuroscience source is the fruit fly Drosophila. The simulation is still based on a Braitenberg slug with distinct circuits for chemotaxis and for obstacle avoidance.

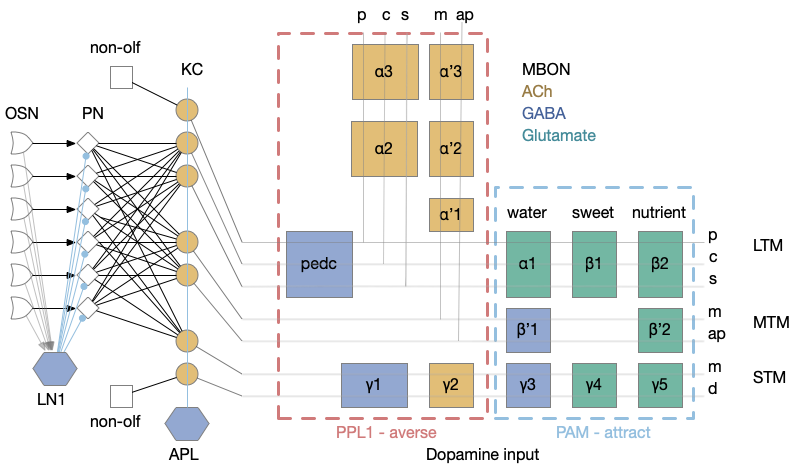

Mushroom body model

The fruit fly mushroom body (MB) is the learning center. MB is a modulating system: if it’s knocked out, the fruit fly behaves normally, although with only intrinsic, unlearned behavior. Essay 16 focuses on a single MBON short term memory (STM) output neuron, which may specifically be the γ2 neuron.

For simplicity and focus, essay 16 isn’t implementing the KC yet. Instead, the γ2 MBON receives its input directly from a small number of odor projection neurons (PN) that was implemented in essay 15. Essentially, the input is a small set of primitive odors, where the full KC is a massive combinatorial odor spectrum.

Candidate odors from evolution

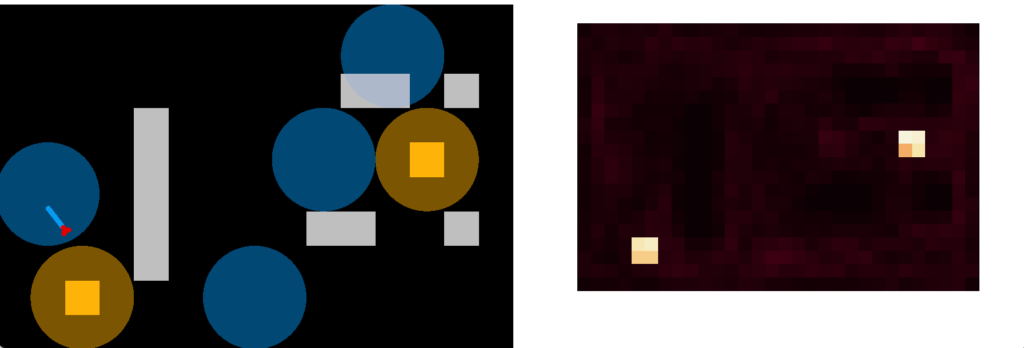

To motivate why evolution might develop learning, consider the food-seeking slug from essay 15. Since the food odor in essay 15 perfectly predicted food, there was no reason to learn anything about food. The simulation’s “evolution” has perfectly solved the artificially perfect world, selecting exactly those odors needed to find food.

Choosing the right set of candidate odors is a dilemma for evolution. Too many candidates means wasted search time. Too few candidates avoids wasted time, but misses out on opportunities, which may be a smaller problem than too many candidates because the animal can fall back to random, brownian-motion search. This beast against including semi-predictive odors might mean that early Precambrian evolution might only favor the highest predictors and skip semi-productive odors.

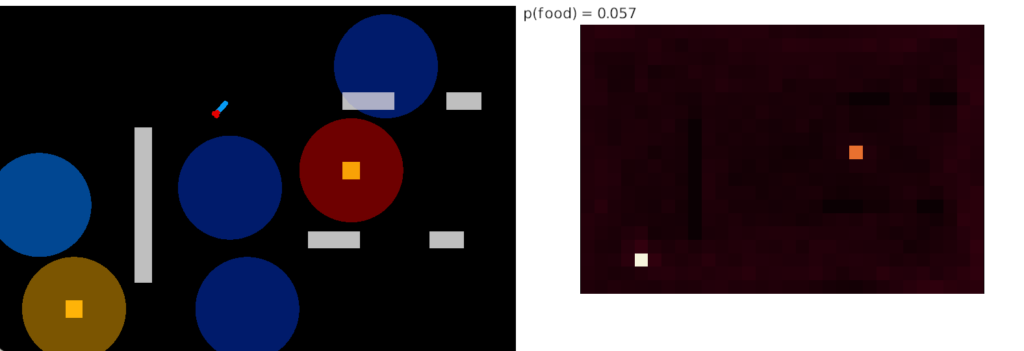

The preceding image represents odors potentially available to the slug from an evolutionary design perspective. If the beige color is the only candidate for food, the slug will ignore the blue-ish colors because it never senses the odor. There’s no need for a circuit or behavior to distinguish the two. For the animal, those odors don’t exist.

Food odors don’t perfectly predict food, either because of lingering odors or simply candidate odors that aren’t always from nutritious food. For example, the fruit fly can taste sweet and it can also sense nutrition from a rest in blood sugar. That distinction between sweet and nutritious is reflected in the mushroom body with specific neurons for each [Owald et al. 2015].

Classical association

For this essay, let’s explore what could be the most trivial memory, in the context of the fruit fly MB. The MB output has only 24 neurons in 15 distinct compartments per hemisphere. Each compartment appears to have specialized roles, such as short term memory (STM) vs long term memory (LTM) [Bouzaiane et al. 2015], and water seeking compared to sugar seeking [Owald et al. 2015].

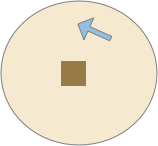

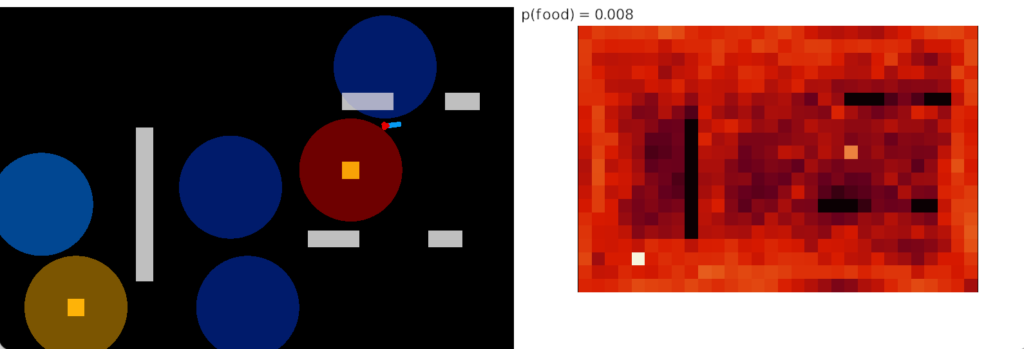

Although learning studies typically use classical association (Pavlovian) terminology, where a conditioned stimulus (CS) like the food odor becomes associated with an unconditioned stimulus (US) like consuming food, I don’t think that framing is useful for the odor-seeking behavior of the simulated slug.

In the diagram above, which follows the classical model, the animal (arrow) missing the food (brown square) despite being in the candidate odor’s plume because it hasn’t learned the associate the odor (CS) with the food (US). It only learns the association if it finds the food through brownian random search. Even then, if it randomly hits another food source with a different odor, it will forget the first, limiting the gain from this learning.

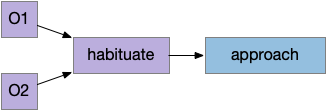

Even the non-learning algorithm of essay 14 performs better, because naive searching of all candidate odors is relatively successful, even if slightly time inefficient. Behaviorally, the difference is between default-approach or default-ignore. Default-approach needs to learn to ignore and default-ignore needs to learn to approach.

Learning to ignore

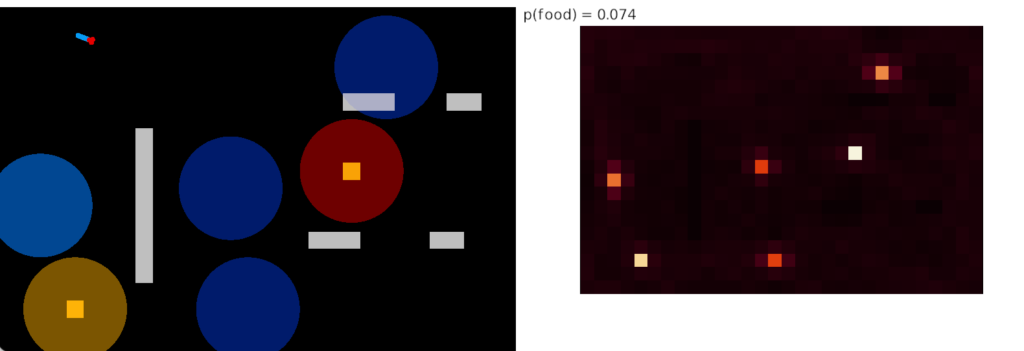

Learning to ignore is an alternative to the classical associative way of looking at the problem. It’s not an argument against classical conditioning in total, but it is a different perspective that highlights different features of the problem.

The diagram above shows a successful approach to food and an unsuccessful approach. Both candidate odors potentially signal food because evolution ignores useless odors, but in this neighborhood the reddish odor is a non-food signal. As in essay 14, habituation will rescue the animal from perseveration, spending infinite time exploring a useless odor, but once an odor is found useless, ignoring it from the start would improve search efficiency.

Since odors in a neighborhood are likely similar, the animal is likely to encounter the useless odor soon. So, remembering a single item, like a single item cache, will improve the search by avoiding cost, until the animal reaches an area that does have nutritious food. The single-item cache lets the animal ignore patches of non-predictive odors.

Single item cache (short term memory)

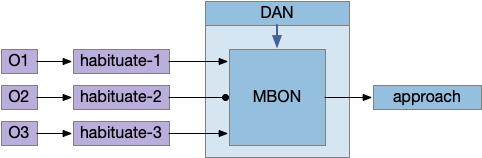

A single mushroom body output neuron (MBON) and its associated dopamine neuron (DAN) can implement a single item cache by changing the weights of the KC to MBON synapses with long-term depression (LTD). Following the previous discussion, since it’s more efficient to remember the last failure than the last success, the learning is LTD at the synapse between the odor and the MBON. In fruit flies, short term memory (STM) is on the order of 2h. (For a fuller discussion between “short” and “long” term see [Sossin 2008].)

In the above diagram, the O2 synapse with a ball represents the LTD cache item. If the animal senses odors for either O1 or O3, it approaches the odor. If it senses O2, it ignores the odor because of the LTD at the synapse. (The colors follow the mnemonic model. Purple represents primary sensor/odor, and blue represents apical/limbic/odor and motivation areas.)

The DAN needs to implement a failure signal to implement LTD, which is actually relatively complicated. Unlike success, which has an obvious direct stimulus when finding food, failure is ambiguous. How long the animal should persist before giving up is a difficult problem, and at very least requires a timer even for the simplest strategy. Because habituation already implements a timeout, an easy solution is to copy the circuit or possibly use its output. So, if the animal exists the odor plume because of habituation, the DAN might signal failure.

Another possibly strategy is for the DAN to continuously degrade the active signal as in habituation, and only rescue the synapse when discovering food. Results from [Berry et al. 2018] show the needed degrading over time (ramping LTD) in their study of MBON-γ2, although that study didn’t explore the rescuing of approach by finding food that we seed.

So, the second strategy might require a second, opposing neuron, which I’ll probably explore later. For this essay, the DAN will produce a failure signal on timeout and a success signal on finding food, something like a reward prediction error signal from reinforcement learning [Sutton and Barto 2018], but without using a reinforcement learning architecture.

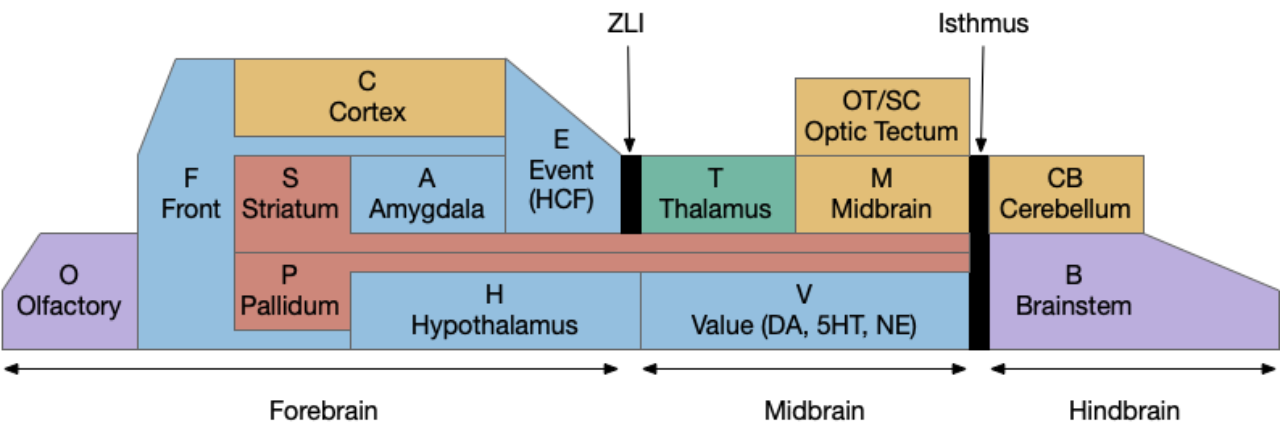

Mammalian correlates

In mammals, the KC/MBON synapse with DAN modulation circuit functionally resembles the hippocampus CA3 to CA1 synapse (E.hc, E.ca1, E.ca3) with locus coerulus (V.lc). In mammals, V.lc is known as the primary source of noradrenaline, associated with surprise and orientation, but it also contains dopamine neurons, and strongly innervates the hippocampus.

[Aston-Jones and Cohen 2005] discuss the locus coeruleus involvement in decision-making, specifically in explore vs exploit decision. If time passes and exploitation continues to fail by not finding food, V.lc signaling encourages moving on and exploring different options, a behavior similar to ours.

The E.ca3 to E.ca1 connection (and E.ec, entorhinal cortex) is believed to detect novelty, and V.lc is active during exploration, Like the fruit fly MBON, the hippocampus uses LTD to learn a new place, using V.lc signal [Lemon et al. 2012] like the DAN.

In contrast with my simulated slug, since the E.hc novelty output doesn’t directly drive food approach, because the mammalian brain is far more complex and abstract, the comparison isn’t exact, but it is an interesting similarity.

Simulation: shared habituation

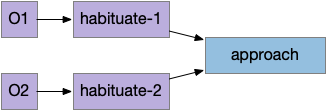

In essay 15, the simulated slug approached an intrinsically attractive odor to find food, but needed a habituation circuit to avoid perseveration. The fruit fly LN1 neurons between the ~50 main olfactory sensory neurons (ORN) and the ~150 olfactory projection neurons (PN) implement primary olfactory habituation. In this essay, I’m essentially adding a second odor to the system. Although the fruit fly has separate habituation circuits for each of the 50 primary odors, it’s interesting to see what a shared habituation circuit might look like in the simulation.

The simulation heat map shows the animal spends much of its time between the odor plumes because the habituation timeout keeps refreshing, despite encountering different odors. While habituation is active, the animal doesn’t approach either odor plume, but mostly moves in the default semi-random pattern. Only when habituation times out will it approach a new odor.

Split habituation

The fruit fly has a split habituation unlike the previous simulation. Each primary odor has an independent habituation circuit, which is synapse specific.

In the simulation of split habituation, the animal spends more time investigating the odors because each new odor has its own habituation timeout. It can move from a failed odor and immediately explore a new odor.

Although the animal spends much of its time exploring the distractor candidate odors, it’s still a big improvement over random search, because it’s more likely to find food instead of a near miss.

Single distractor

Since a single distractor exactly fits the single item cache, it’s unsurprising that adding the cache immediately solves the distractor problem. In the following heat map, the animal only explores the successful candidate odor and ignores the distractor.

Multiple odors and distractors

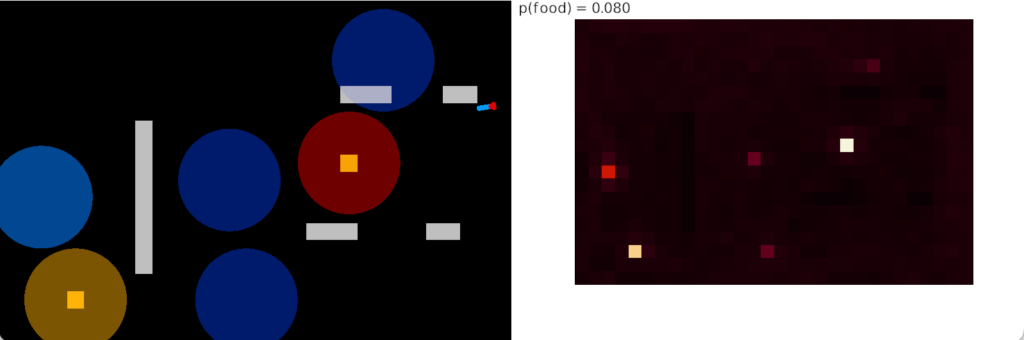

Multiple distractor odors is more interesting for a single item cache because it introduces miss-rate as a prominent issue and allows comparison between negative caching and positive caching (classical association). The table below is a summary of feeding time as a success metric for each strategy.

| Algorithm | Feeding time |

| No odor approach | 0.8% |

| No learning | 7.4% |

| LTD (cache) | 8.0% |

| LTP (classical) | 5.7% |

No odor approach

As a baseline, the first simulation disables all odor approach. The animal only reaches food when it runs into it randomly. While it’s above the food, the animal will slow, improving its efficiency somewhat. This strategy was explored in essay 14, and resembles the feeding of Trichoplax in [Smith et al. 2015].

As the heat map shows, this strategy is pretty terrible. Because the animal only finds food by randomly crossing it, its success rate is purely a matter of the area covered by food. Although this strategy may have been effective with Precambrian bacteria mats, where finding food isn’t an issue, it’s a problem when finding food is a necessary task.

No learning

Intrinsic chemotaxis is important as a baseline for the learning strategies. In the fruit fly intrinsic odor approach behavior is in the lateral horn. When the MB is disabled, the lateral horn continues to approach odors.

As the above heat map shows, intrinsic odor approach is a vast improvement over non-chemotaxis, improving food time from 0.8% to 7.4% in this environment.

Negative caching (LTD)

The single item caching that’s the focus of this post improves the food time from 7.4% to 8% by avoiding some of the time spent on non-food odors. The difference isn’t as dramatic as adding odor approach itself, but it’s an improvement.

In this strategy, the animal remembers the last failure odor, and ignores the odor plume the next time it reaches it. The animal explores all other odors, including failure odors. On a cache miss (failure), the animal remembers the new failure and forgets the old one.

Classical conditioning (LTP)

The next strategy tries to simulate what classical conditioning might look like if it was used for behavior. In this simulation, the animal only follows the odor after it’s associated with food, which means the animal needs to randomly discover the food first.

This strategy is actually worse than the non-learning case, because it only finds one food source at a time. Although the heat map shows both being visited, the areas are actually alternating. One source is the only found food for a long time until the other is randomly discovered, when the roles switch and the first is now ignored.

Simulation limitations

I think it’s important to point out some simulation limitations, particularly since I’ve added performance numbers for comparison. The simulation environment and timings can affect the numbers dramatically. For example, the odor plume size dramatically affects the classical conditioning algorithm. If finding food without following the odor is difficult, the classical conditioning animal will have great difficulty finding a new odor.

Specifically, if the gain from following the odor is large, then classical conditioning will always have a penalty, because it loses out on that gain until it makes its association. In contrast an explore-first strategy will always gain the odor-exploring advantage. If the gain of explore-first outweighs its cost, then a non-learning explore-first will win against associative learning.

cost_cache = p_miss * cost_miss + (1 - p_miss) * cost_hit

cost = cost_cache + cost_noncacheConsider the rough cache cost model above to see some of the issues with the negative cache. If the non-cacheable cost greatly outweighs the cache miss cost, then it doesn’t matter if the animal learns to avoid irrelevant odors. Contrariwise, if the miss cost is very large, then the miss rate is critical.

In addition, the miss rate is highly dependent on spatial and temporal locality. If similar odors are tightly grouped, even a small cache will have a low miss rate. But if there are many different distractor types spread randomly, the cache will miss most of the time.

Links

- Essay 16a: What is “Short Term Memory” for Neurons

- Essay 16b: Classical Conditioning and Negative Learning

- Essay 16c: Give-Up Time in Foraging

- Essay 17: Proto-Vertebrate Locomotion

- Essay 31: Odor Seek with Striatum Timeout

References

Aso Y, Hattori D, Yu Y, Johnston RM, Iyer NA, Ngo TT, Dionne H, Abbott LF, Axel R, Tanimoto H, Rubin GM. “The neuronal architecture of the mushroom body provides a logic for associative learning.” Elife. 2014

Aston-Jones, Gary, and Jonathan D. Cohen. “An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance.” Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 28 (2005): 403-450.

Berry JA, Phan A, Davis RL. “Dopamine Neurons Mediate Learning and Forgetting through Bidirectional Modulation of a Memory Trace.” Cell Rep. 2018

Bouzaiane E, Trannoy S, Scheunemann L, Plaçais PY, Preat T. “Two independent mushroom body output circuits retrieve the six discrete components of Drosophila aversive memory.” Cell Rep. 2015 May 26;11(8):1280-92.

Lemon N, Denise Manahan-Vaughan, “Dopamine D1/D5 Receptors Contribute to De Novo Hippocampal LTD Mediated by Novel Spatial Exploration or Locus Coeruleus Activity, Cerebral Cortex,” Volume 22, Issue 9, September 2012, Pages 2131–2138.

Owald D, Felsenberg J, Talbot CB, Das G, Perisse E, Huetteroth W, Waddell S. “Activity of defined mushroom body output neurons underlies learned olfactory behavior in Drosophila“. Neuron. 2015 Apr 22

Smith CL, Pivovarova N, Reese TS. “Coordinated Feeding Behavior in Trichoplax, an Animal without Synapses.” PLoS One. 2015 Sep 2

Sossin, Wayne S. “Defining memories by their distinct molecular traces.” Trends in neurosciences 31.4 (2008): 170-175.

Sutton, R. S., & Barto, A. G. (2018). Reinforcement learning: An introduction. MIT press.