Although the touch sense is a baseline implementation of obstacle avoidance, the essay’s animal should avoid obstacles before bumping into them, but it needs a new, ranged sense. The aquatic vertebrate lateral line senses obstacles, peer, predators, and prey at a distance of around the animal’s length. The lateral line is a basal vertebrate sense, lost in land vertebrates that’s a twin sense to weak electro sensation. Adding a lateral line sense to the toy model will let the simulated animal avoid walls before bumping into them.

Lateral line sense

The lateral line is an aquatic-only primitive vertebrate sense lost in terrestrial animals. Like mouse whisker, inner ear hearing and vestibular sensing, it’s a hair-based object-distance sensor that senses obstacles, peers, predators, and prey with a distance of about the animal’s length. Unlike mouse whiskers but like hearing and vestibular, the lateral line doesn’t touch the obstacle directly, but senses water movement, and from that motion can infer the presence of obstacles. The lateral line sensors are hair-like neuromasts that line the animal’s body along the entire length [Braun and Coombs 2000], [Chagnaud et al 2017].

Although the diagram above implies that the lateral line sense is a simple distance measurement, the actual sense is a complicated measurement of fluid dynamics and how water flow changes near obstacles. To further complicate the sense, the animal’s own motion changes the water flow. All vertebrates with the lateral line have a cerebellum-like nucleus to cancel out self motion called MON (medial octavolateral nucleus). Electrosensing fish have another cerebellum-like nucleus to cancel its own electric field called DON (dorsal octavolateral nucleus) [Bell et al. 2008]. For this essay I’m completely ignoring all these real complications and will simply use lateral line as a distance measurement.

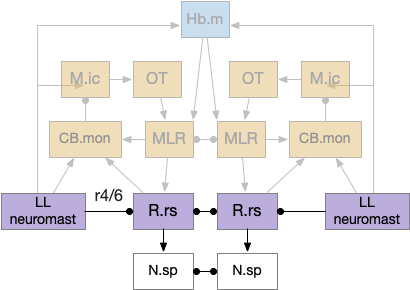

The LL (lateral line) divides into two disjoint circuits, LL.a (anterior lateral line) covering the head before the ear, and LL.p (posterior lateral line) covering the trunk and tail behind the ear. LL.a connects to the hindbrain at R4 and LL.p connects at R6 [Chagnaud et al 2017]. The lateral line directly innervates the R.rs (reticulospinal) fast escape motor control neurons, including the paired giant Mauthner cells in R4 which trigger fast escape [Mirjany et al 2011].

Although hearing, vestibular, and lateral line use hair sensor sells, they are evolutionary independent [Chagnaud et al 2017]. Because both hearing and LL sense water oscillations, their signals overlap in frequency [Braun and Coombs 2000], with hearing sensing frequencies over 50Hz and LL sensing frequencies below 50Hz.

Lateral line circuits

Because this essay only uses LL for obstacle avoidance, it only implements the direct LL to R.rs connection, inhibiting movement toward an obstacle. The full LL circuit includes input to M.ic (inferior colliculus, hearing) and OT (optic tectum, blindsight) for higher-level navigation. The LL output to Hb.m (medial habenula) exists in the lamprey [Stephenson-Jones et al 2012] although possibly only the electrosensory LL and is used for thigmotaxis (wall hugging).

To break down the circuit, first consider the fast escape Mauthner cell in r4 (hindbrain rhombomere 4), which connects directly to fast-twitch muscles. For an early vertebrate, a nearby predator could trigger the lateral line, which then triggered the Mauthner cell for a fast escape. The essay’s simulation uses the same circuit, but for obstacle avoidance instead of escape because I haven’t added any predators yet.

Next consider the thigmotaxis circuit using Hb.m (medial habenula) for gradient descent, where LL replaces the phototaxis light/dark gradient in essay 24 or chemotaxis odor gradient in essay 26. The lateral line gradient of water movement as the animal nears an obstacle drives Hb.m to balance wall avoidance with wall hugging. Note that the nAChR (nicotinic receptor) from R.ip (interpeduncular nucleus) to P.ldt (laterodorsal tegmental nucleus) is a goldilocks attract / avoid circuit [Wolfman et al 2018], which is the diagram’s Hb.m to MLR connection. At a distance, the weak glutamate-only R.ip to P.ldt signal is attractive, but nearby the stronger ACh amplification switches to aversion. The “nicotinic” is important here, because nicotine as a drug acts here for both nicotine’s attraction at low doses and its aversion at high doses. (Note: in this case “gradient descent” is the correct term, because the animal has a target distance so either too close or too far forms a signed error.)

Next consider the unmodulated LL to M.ic (inferior colliculus / torus semicircularis) to OT (optic tectum) circuit. Even ignoring optic input, OT has an egocentric map of sensory input, including the lateral line. Since the lateral line neuromasts are distributed across the animal’s body and head, each neuromast can give location-specific information about the distance to the obstacle or threat. The LL data becomes a marker on the OT map, enabling a more sophisticated OT navigation, where all the obstacles are marked on the map.

Finally consider the adaptive filter improvement from CB.mon (medial octavolateral nucleus) as a noise-cancelling system, where the noise is self-generated motion affecting the LL signal. CB.mon uses motor efference copies from MLR and B.rs and LL sensor input to predict the self-motion effect on LL. It sends the self-motion prediction to M.ic allowing M.ic to both filter out the self-motion, but also retain the unfiltered input. After filtering out self-motion, the remaining signal better represents the obstacles or threats. Although this signal could be called a prediction error, I think using filtered signal is a clearer and more useful description because the prediction itself is merely instrumental in producing a useful signal.

Cerebellum-like circuits

CB.mon (medial octavolateral nucleus) in the diagram above is a cerebellum-like system [Bell et al 2008], [Montgomery et al 2012]. Cerebellum-like systems are adaptive filters that remove predictable self-generated signals from self-motion. Because LL measures water motion but swimming also produces water motion, LL will primarily measure the animal’s own motion, unless the animal has paused. Since the self-motion would swamp the signal from obstacle, predators, or prey, CB.mon cleans up the signal by filtering out self-motion.

Social lateral line modulation

Modern fish are far more advanced animals than the simulation and famously swim in schools. The proximity of peer fish adds complexity to the lateral line. The fish needs to allow the peer to come nearer than a predator or even an obstacle.

Since lateral line is old, it’s unsurprising that schooling behavior is peptide-modulated. In zebrafish the neuropeptide pth2 reduces lateral line sensitivity and allows for closer schooling [Anneser et al 2020]. This effect is modulated by fish models of social anxiety, where anxious fish use larger distancing [Anneser et al 2022].

References

Anneser L, Alcantara IC, Gemmer A, Mirkes K, Ryu S, Schuman EM. The neuropeptide Pth2 dynamically senses others via mechanosensation. Nature. 2020 Dec;588(7839):653-657.

Anneser L, Gemmer A, Eilers T, Alcantara IC, Loos AY, Ryu S, Schuman EM. The neuropeptide Pth2 modulates social behavior and anxiety in zebrafish. iScience. 2022 Feb 4;25(3):103868.

Bell, Curtis C., Victor Han, and Nathaniel B. Sawtell. Cerebellum-like structures and their implications for cerebellar function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 31 (2008): 1-24.

Braun CB, Coombs S. The overlapping roles of the inner ear and lateral line: the active space of dipole source detection. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2000 Sep 29;355(1401):1115-9.

Chagnaud BP, Engelmann J, Fritzsch B, Glover JC, Straka H. Sensing External and Self-Motion with Hair Cells: A Comparison of the Lateral Line and Vestibular Systems from a Developmental and Evolutionary Perspective. Brain Behav Evol. 2017;90(2):98-116.

Mirjany M, Preuss T, Faber DS. Role of the lateral line mechanosensory system in directionality of goldfish auditory evoked escape response. J Exp Biol. 2011 Oct 15;214(Pt 20):3358-67.

Montgomery, John C., David Bodznick, and Kara E. Yopak. The cerebellum and cerebellum-like structures of cartilaginous fishes. Brain, behavior and evolution 80.2 (2012): 152-165.

Stephenson-Jones M, Floros O, Robertson B, Grillner S. Evolutionary conservation of the habenular nuclei and their circuitry controlling the dopamine and 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HT) systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Jan 17;109(3):E164-73.

Wolfman SL, Gill DF, Bogdanic F, Long K, Al-Hasani R, McCall JG, Bruchas MR, McGehee DS. Nicotine aversion is mediated by GABAergic interpeduncular nucleus inputs to laterodorsal tegmentum. Nat Commun. 2018 Jul 13;9(1):2710.