Because sleep is a global state that suppresses senses and actions, its control circuitry affects essentially all neural systems. For example, an article on dopamine and S.v (ventral striatum aka nucleus accumbens) suggested that dopamine acts more like a wake signal than an abstract reward signal [Kazmierczak and Nicola 2022]. If that explanation is accurate, then understanding the sleep system is a prerequisite for understanding the whole system.

From the study, low dopamine caused the rodents to either fall asleep normally or collapse in cataplexy, depending on whether D1s (stimulating Gs-coupled dopamine receptor) or D2i (inhibitory Gi-coupled dopamine receptor) were disabled. Many studies omit qualitative behavior like animals falling asleep, reporting only statistical summaries of success or failure.

The Great Oxidation Event

Sleep exists for essentially all animals including primitive animals like hydra and even single celled eukaryotes. Beyond sleep, oxidation-reduction cycles exist even for bacteria. 2.5 billion years ago in the Great Oxidation Event when photosynthesis created the toxin oxygen, most life died except for like that developed defenses against oxidation and ROS (reductive oxygen species). One of these cellular defenses was an oxidation-reduction cycle to spend time repairing oxygen damage. Cellular clocks developed around these primitive, conserved oxidation-reduction cycles [Edgar et al 2012].

Mitochondria in eukaryotes produce additional toxic oxygen ROS. One general sleep theory proposes that mitochondria force sleep on their hosts to allow for repair [Hartman and Kempf 2023]. In essentially all cells the cell clock and the mitochondrial clock are in sync [Scrima et al 2016]. In this model, sleep repairs oxidation damage in a quiet, low energy mode. Mitochondria produce GABA to signal to the host cell for its sleep need [Adams and O’Brien 2023]. GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter, possibly directly inhibiting the containing neuron.

In the cortex a more sophisticated system passes damaged mitochondria from neurons to astrocytes, when then modulate sleep [Haydon 2017]. Astrocytes strong coupling between sleep and neural activity is important in many brain areas. In particular, astrocytes emit sleep transmitters adenosine and GABA, and connect to neighboring astrocytes with gap junctions to integrate sleep pressure spatially and temporally. Astrocyte can emit adenosine and GABA, both sleep signals. So, sleep can’t be treated as a straight neural circuit without considering the actions of astrocytes.

Beyond the brain, metabolic cells such as the liver and even gut microflora have circadian cycles and these metabolic cycles work best when synchronized with sleep [Borbély et al 2016].

Sleep basics

While sleep in mammals can be detected by slow waves in the cortex, a more general criteria is necessary to cover insects like Drosophila and worms like C. elegans. The following properties are generally used to identify sleep:

- Behavioral quiescence

- Sensory inhibition

- Sleep position

From an implementation perspective, sleep has a global coordination problem because all processes need to sleep simultaneously. In contrast, waking processes such as foraging only needs to activate task-relevant areas, and other areas can rest outside of a general sleep state. Columns in the cortex, for example, can fall into a slow wave state while the animal is awake. Although no lesion of the brain produces a wake-only state [Krueger et al 2013], so there is no single sleep center, sleep requires global coordination.

- Inhibit the link from stimulus to response

- Inhibit intrinsic motivation

- Inhibit cognitive processes

Two process model of sleep

The two process model of sleep considers circadian and homeostatic as two separate processes driving sleep. In addition, the animal’s activity can postpone sleep [Yamagata et al 2021]. Circadian sleep handles the major daily sleep need while homeostatic sleep covers local sleep needs.

Criticisms of this model point out metabolic anabolic and catabolic cycles are more related to feeding cycles than light cycles [Borbély et al 2016]. The presence of cell clocks in most cells suggests that circadian isn’t a global requirement. In addition, ultradian (4h) feeding cycles cause food anticipatory activity [Dibner et al 2010].

As a specific counterexample, the snail sleep can be model well by simple stochastic oscillator between wake and quiescence [Stephenson 2011]. In contrast zooplankton follow a clear circadian migration between light and dark [Tosches et al 2014].

From a circuit perspective, the two process model has value because some areas like Hb (habenula), Po.vl (ventrolateral preoptic area), and H.scn (suprachiasmatic nucleus) are more easily understandable from a circadian perspective.

Bistable sleep and wake

Although it might sound obvious that sleep and wake are distinct states, implementing this bistable system requires coordination. Violations of this bistability are unusual, like sleepwalking. As in essay 27, where the state transition between seeking food and eating required a circuit using H.stn (subthalamic nucleus) and Snr (substantia nigra pars reticulata), the sleep and wake circuits need circuits to manage their distinction and transition.

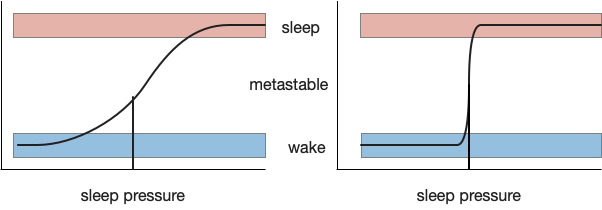

Clear state transitions try to avoid metastability, a transitional non-state between the target states. Metastability always exists, but can be minimized by increasing the feedback gain between the states. A high gain, tight transition minimizes the probability of a metastable state. In the mammalian brain, positive feedback and lateral inhibition in Po.vl (ventrolateral preoptic area) and H.l.ox (orexin area of lateral hypothalamus) help make the switch tighter. [Saper et al 2001] calls this a flip-flop with the similarity to bistable electrical latches, where a high gain to avoid metastability is also very important to maintain binary values with a continuous voltage.

While high gain and lateral inhibition is important for sleep, an additional concept called hysteresis is also important to create long continuous sleep bouts and avoid sleep fragmentation.

Hysteresis: sticky switches

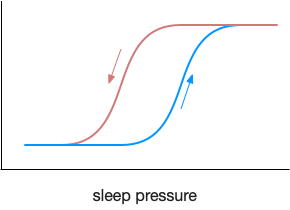

In a naive implementation of homeostatic sleep, the animal sleeps when sleep pressure rises past a threshold, and wakes when the pressure drops. Unfortunately, this system could quickly oscillate, where a short nap of a few seconds crosses the threshold and wakes the animal, which quickly tires and takes a new nap. To avoid this fragmented sleep, the threshold needs to be sticky: it’s harder to wake when the animal sleeps, and harder to sleep when the animal wakes.

This kind of sticky switch is called hysteresis. The threshold for switching states depends on the current state.

Since sleep inhibits sensory input, noises that would keep an animal awake are ignored. Since sleep inhibits actions, the animal is unlikely to run into a situation that requires action. On the other side, any ongoing action will maintain wake. The transition to sleep needs to be slow to ensure that all actions have completed. In addition, long lasting peptides like orexin from H.l can maintain wake for minutes, ensuring a minimum wake bout length.

Note that circadian sleep process is another solution to the sleep oscillation problem. Because time is inexorable, circadian sleep time also shifts the sleep threshold, making it increasingly difficult to sustain wake.

Sleep and wake asymmetry

Sleep and wake are asymmetrical, unlike a symmetrical flip-flop. Any ongoing action needs to maintain wake, and falling asleep is a slow, decaying process, but waking needs to be fast when responding to an alarm. This asymmetrical slow drop to sleep and quick rise to wake is reflected in neurotransmitter levels like dopamine [Zhang et al 2023].

In terms of circuitry, an area around R.pb (parabrachial nucleus) is required for wake. If that area is lesioned, the animal remains in a coma [Fuller et al 2011]. There is no equivalent sleep area that produces a wake-only state when lesioned [Krueger et al 2013].

Next: circadian

After the general discussion of sleep, I think exploring the circadian aspect of sleep is a good direct. Circadian sleep is an ancient system, existing in zooplankton and preexisting more complicated sleep systems.

References

Adams GJ, O’Brien PA. The unified theory of sleep: Eukaryotes endosymbiotic relationship with mitochondria and REM the push-back response for awakening. Neurobiol Sleep Circadian Rhythms. 2023 Jul 6;15:100100.

Borbély AA, Daan S, Wirz-Justice A, Deboer T. The two-process model of sleep regulation: a reappraisal. J Sleep Res. 2016 Apr;25(2):131-43.

Dibner, C., Schibler, U., & Albrecht, U. (2010). The mammalian circadian timing system: organization and coordination of central and peripheral clocks. Annual review of physiology, 72, 517-549.

Edgar RS, Green EW, Zhao Y, van Ooijen G, Olmedo M, Qin X, Xu Y, Pan M, Valekunja UK, Feeney KA, Maywood ES, Hastings MH, Baliga NS, Merrow M, Millar AJ, Johnson CH, Kyriacou CP, O’Neill JS, Reddy AB. Peroxiredoxins are conserved markers of circadian rhythms. Nature. 2012 May 16;485(7399):459-64.

Hartmann C, Kempf A. Mitochondrial control of sleep. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2023 Aug;81:102733.

Haydon PG. Astrocytes and the modulation of sleep. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2017 Jun;44:28-33.

Kaźmierczak M, Nicola SM. The Arousal-motor Hypothesis of Dopamine Function: Evidence that Dopamine Facilitates Reward Seeking in Part by Maintaining Arousal. Neuroscience. 2022 Sep 1;499:64-103.

Krueger JM, Huang YH, Rector DM, Buysse DJ. Sleep: a synchrony of cell activity-driven small network states. Eur J Neurosci. 2013 Jul;38(2):2199-209.

Saper, C. B., Chou, T. C., & Scammell, T. E. (2001). The sleep switch: hypothalamic control of sleep and wakefulness. Trends in neurosciences, 24(12), 726-731.

Scrima R, Cela O, Merla G, Augello B, Rubino R, Quarato G, Fugetto S, Menga M, Fuhr L, Relógio A, Piccoli C, Mazzoccoli G, Capitanio N. Clock-genes and mitochondrial respiratory activity: Evidence of a reciprocal interplay. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016 Aug;1857(8):1344-1351.

Stephenson R. Sleep homeostasis: Progress at a snail’s pace. Commun Integr Biol. 2011 Jul;4(4):446-9.

Tosches MA, Bucher D, Vopalensky P, Arendt D. Melatonin signaling controls circadian swimming behavior in marine zooplankton. Cell. 2014 Sep 25;159(1):46-57.

Yamagata T, Kahn MC, Prius-Mengual J, Meijer E, Šabanović M, Guillaumin MCC, van der Vinne V, Huang YG, McKillop LE, Jagannath A, Peirson SN, Mann EO, Foster RG, Vyazovskiy VV. The hypothalamic link between arousal and sleep homeostasis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Dec 21;118(51):e2101580118.

Zhang J, Peng Y, Liu C, Zhang Y, Liang X, Yuan C, Shi W, Zhang Y. Dopamine D1-receptor-expressing pathway from the nucleus accumbens to ventral pallidum-mediated sevoflurane anesthesia in mice. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2023 Nov;29(11):3364-3377.