The ascidian circuit in essay 30 had an interesting dopamine subcircuit that looks like an indirect search, where the ascidian coronet cells modulate the underlying phototaxis and geotaxis circuits. While the function of the coronet cells is unknown, if these cells are another seeking system like following an odor, then the coronet sub circuit follows odor by modulating different seek circuits: phototaxis and geotaxis.

Ascidian analogy

Tunicates are the closest non-vertebrate chordates evolutionarily, but they have developed in vastly different directions from the vertebrates, and likely very differently from the shared common ancestor [Holland 2015]. The ascidian tunicates, which are the most studied tunicates, live their asul life as sessile filter feeders like sponges. Their eggs hatch in only 20 hours and their brief tadpole form lasts only for a few hours, just enough to swim and disperse to find a likely permanent settlement place. Their locomotive strategy is to swim up using geotaxis in the morning and swim down using phototaxis in the afternoon. If they’re lucky enough to find a ledge, they swim up into the ledge’s shadow to settle because hanging like a bat from a ledge offers more protection from some predators than resting on the ocean floor [Zega et al 2006].

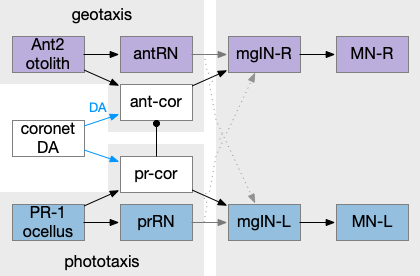

As would be expected from a 20-hour brain, the navigation circuit is fairly simple. There are two distinct action paths, one for geotaxis using a heavy pigment cell and one for phototaxis using photoreceptors and another pigment cell as a shadow to provide photo-directionality. The two action paths are connected, where dimming produces upward swimming [Bostwick et al 2020].

In the above diagram, the geotaxis action path starts from the otolith (“ear stone”) receptor ant2, which is functionally similar to the vestibular system (but not related), passes input to antenna relay neurons (antRN) and then to the right side motor neurons (mgIN-R and MN-r) [Ryan et al 2016]. Similarly, the phototaxis action path starts from the ocellus (eyespot) to the phototaxis relay (prRN) and to the left motor neurons, providing an opposing direction from geotaxis. Importantly for the following discussion, each path has a weak connection to the opposite direction, possibly to add some stochasticity to the movement to improve dispersion of the many tadpoles.

The function of the coronet cells is unknown, although they have some genetic connection the palp sensory cells [Cao et al 2019]. Other papers compare the corona cells to dopamine cells in the hypothalamus and Ob (olfactory bulb) [Horie et al 2018] or ancestral photo-hypothalamus and retina [Sharma et al 2019], possibly related to the fish saccus vasculosus area of the hypothalamus, responsible for some circadian behavior. However, the ascidian tadpole has lost circadian clock genes, which argues against circadian timing [Chung et al 2023]. The coronet cells can accumulate serotonin and the DA might promote onset of metamorphosis [Razy-Kraika et al 2012]. So, the coronet may be involved in triggering metamorphic changes at twilight, which causes the tadpole to dive to deeper waters [Lemaire et al 2021].

Whatever the source, the interesting thing about the circuit is that it’s an indirect modulation of underlying taxis action paths. The action of the coronet is gating or modulatory. While this coronet circuit is not homologous to the basal ganglia, using it as an analogy may be useful. For example, dopamine is a sleep / wake signal for the basal ganglia [Vetrivelan et al 2010]. Because low dopamine reduces basal ganglia activity both at the striatum input layer and the Snr (substantia nigra pars reticulata) output layer, it’s an effective sleep controller.

Indirect chemotaxis

Consider indirect chemotaxis, where the animal is seeking toward the odor, but the underlying action path is phototaxis or geotaxis, like the ascidian circuit above. If the animal detects an odor, it increases the current direction. In other words, the current direction is toward or near a food odor. This strategy is like the e. coli tumble-and-run strategy, where the bacteria runs further when the odor gradient is increasing.

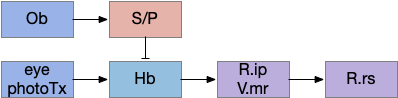

Consider the basal ganglia as an analogy. For example, Ob has some dopamine interneurons (Ob.sac – short axis cells) that project to S.ot (olfactory tubercle) [Burton 2017], a portion of the stratum focused on olfactory input. For the corollary of the phototaxis path, consider the Hb.m (medial habenula) phototaxis path [Zhang et al 2017].

When the odor is detected, Ob enables the basal ganglia, which enhances the phototaxis path. If the odor isn’t detected, the default semi-suppressed behavior means the direction is semi-random. This indirect control would allow for seeking odor when the underlying navigation is phototaxis and geotaxis.

Discussion

After writing this description. I think this model may be a bit sketch for something like chemotaxis, although it’s a reasonable model for sleep. Because I’m not sure the idea is likely to be productive, I’m holding off on doing any implementation, but writing down the description in case it makes sense later.

References

Bostwick M, Smith EL, Borba C, Newman-Smith E, Guleria I, Kourakis MJ, Smith WC. Antagonistic Inhibitory Circuits Integrate Visual and Gravitactic Behaviors. Curr Biol. 2020 Feb 24;30(4):600-609.e2.

Burton SD. Inhibitory circuits of the mammalian main olfactory bulb. J Neurophysiol. 2017 Oct 1;118(4):2034-2051.

Cao C, Lemaire LA, Wang W, Yoon PH, Choi YA, Parsons LR, Matese JC, Wang W, Levine M, Chen K. Comprehensive single-cell transcriptome lineages of a proto-vertebrate. Nature. 2019 Jul;571(7765):349-354.

Chung J, Newman-Smith E, Kourakis MJ, Miao Y, Borba C, Medina J, Laurent T, Gallean B, Faure E, Smith WC. A single oscillating proto-hypothalamic neuron gates taxis behavior in the primitive chordate Ciona. Curr Biol. 2023 Aug 21;33(16):3360-3370.e4.

Holland, L. Z. (2015). Genomics, evolution and development of amphioxus and tunicates: the Goldilocks principle. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution, 324(4), 342-352.

Horie T, Horie R, Chen K, Cao C, Nakagawa M, Kusakabe TG, Satoh N, Sasakura Y, Levine M. Regulatory cocktail for dopaminergic neurons in a protovertebrate identified by whole-embryo single-cell transcriptomics. Genes Dev. 2018 Oct 1;32(19-20):1297-1302.

Lemaire LA, Cao C, Yoon PH, Long J, Levine M. The hypothalamus predates the origin of vertebrates. Sci Adv. 2021 Apr 28;7(18):eabf7452.

Razy-Krajka F, Brown ER, Horie T, Callebert J, Sasakura Y, Joly JS, Kusakabe TG, Vernier P. Monoaminergic modulation of photoreception in ascidian: evidence for a proto-hypothalamo-retinal territory. BMC Biol. 2012 May 29;10:45.

Ryan K, Lu Z, Meinertzhagen IA. The CNS connectome of a tadpole larva of Ciona intestinalis (L.) highlights sidedness in the brain of a chordate sibling. Elife. 2016 Dec 6;5:e16962.

Sharma S, Wang W, Stolfi A. Single-cell transcriptome profiling of the Ciona larval brain. Dev Biol. 2019 Apr 15;448(2):226-236.

Vetrivelan R, Qiu MH, Chang C, Lu J. Role of Basal Ganglia in sleep-wake regulation: neural circuitry and clinical significance. Front Neuroanat. 2010 Nov 23;4:145.

Zega, G., Thorndyke, M. C., & Brown, E. R. (2006). Development of swimming behaviour in the larva of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Journal of experimental biology, 209(17), 3405-3412.

Zhang BB, Yao YY, Zhang HF, Kawakami K, Du JL. Left Habenula mediates light-preference behavior in Zebrafish via an asymmetrical visual pathway. Neuron. 2017;93:914–28.