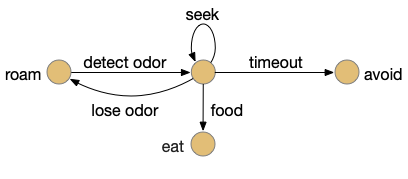

Let’s return to the task of essay 16 on give-up time in foraging, which covered food search with a timeout. At first the animal uses a general roaming search and if it smells a food odor, it switches to a targeted seek following the odor with chemotaxis. If the animal finds food in the odor plume, it eats the food, but if it doesn’t find food, it will eventually give up and avoid the local area before returning to the roaming search.

For another attempt at the problem, let’s take the striatum (basal ganglia) as implementing the timeout portion of this task using the neurotransmitter adenosine as a timeout signal and incorporating the multiple action path discussion from essay 30 on RTPA. Adenosine is a byproduct of ATP breakdown and is a measure of cellular activity. With sufficiently high adenosine, the striatum switches from the active seek path to an avoidance path. These circuits are where caffeine works to suppress the adenosine timeout, allowing for longer concentration.

Mollusk navigation

As mentioned in essay 30, the mollusk sea slug has a food search circuit with a similar logic to what we need here. The animal seeks food odors when it’s hungry, but it avoids food odors when it’s not hungry [Gillette and Brown 2015].

This essay uses the same idea but replaces the hunger modulation with a timeout. When the timeout occurs, the circuit switches from a food seek action path to a food avoid action path.

Odor action paths

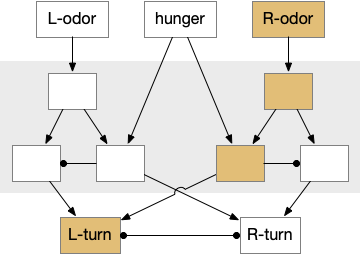

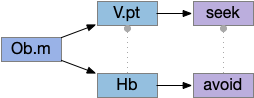

Two odor-following actions paths exist in the lamprey, one using Hb.m (medial habenula) and one using V.pt (posterior tuberculum). The Hb.m path is a chemotaxis path following a temporal gradient. The V.pt path projects to MLR (midbrain locomotor region), but The lamprey Ob.m (medial olfactory bulb) projects to both Hb.m (medial habenula) and to V.pt (posterior tuberculum), which each project to different locomotor paths [Derjean et all 2010], Hb.m to R.ip (interpeduncular nucleus) and V.pt to MLR (midbrain locomotor region). The zebrafish also has Ob projections to Hb and V.pt [Imamura et al 2020], [Kermen et al 2013].

Further complicating the paths, the Hb.m itself contains both an odor seeking path and an odor avoiding path [Beretta et al 2012], [Chen et al 2019]. Similarly Hb.m has dual action paths for social winning and losing [Okamoto et al 2021]. So, this essay could use the dual paths in Ob.m instead of contrasting Ob.m with V.pt, but the larger contract should make the simulation easier to follow.

This essay’s simulation makes some important simplifications. The Hb to R.ip path is a temporal gradient path used for chemotaxis, phototaxis and thermotaxis. In a real-world marine environment, odor diffusion and water turbulence is much more complicated, producing more clumps and making a simple gradient ascent more difficult [Hengenius et al 2012]. Because this essay is only focused on the switchboard effect, this simplification should be fine.

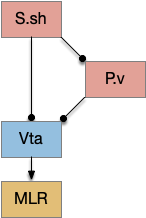

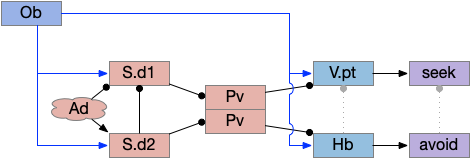

Striatum action paths with adenosine timeout

The timeout circuit uses the striatum, which has two paths: one selecting the main action, and the second either stopping the action, or selecting an opposing action [Zhai et al 2023]. The two paths are distinguished by their responsiveness to dopamine with S.d1 (striatal projection with D1 G-s stimulating) or S.d2 (striatal projection with D2 G-i inhibiting) marking the active and alternate paths respectively. This model is a simplification of the mammalian striatum where the two paths interact in a more complicated fashion [Cui et al 2013].

As mentioned, the two actions paths are the seek path from Ob to V.pt and the avoid path from Ob to Hb. For the timeout and switchboard, the Ob has a secondary projection to the striatum. Although this circuit is meant as a proto-vertebrate simplification, Ob does project to S.ot (olfactory tubercle) and to the equivalent in zebrafish [Kermen et al 2013].

The timeout is managed by adenosine, which is a neurotransmitter derived from ATP and a measure of neural activity. The striatum has three sub-circuits for this kind of functionality, which I’ll cover in order of complexity.

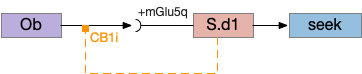

S.d1 and adenosine inhibition

The first circuit only uses the direct S.d1 path and adenosine as a timeout mechanism. When the animal follows an odor, the Ob to S.d1 signal enables the seek action. As a timeout, ATP from neural activity degrades to adenosine and the buildup of adenosine is a decent measure of activity over time. The longer the animal seeks, the more adenosine builds up. Of the Ob projection axis contains an A1i (adenosine G-i inhibitory) receptor, the adenosine will inhibit the release of glutamate from Ob, which will eventually self-disable the seek action.

In practice, the striatum uses astrocytes to manage the glutamate release. An astrocyte that envelops the synapse measures glutamate release with an mGlu5q (metabotropic glutamate with G-q/11 binding) receptor and accumulates internal calcium [Cavaccini et al 2020]. The astrocyte’s calcium triggers an adenosine release as a gliotransmitter, making the adenosine level a timeout measure of glutamate activity. The presynaptic A1i receptor then inhibits the Ob signal. The timeframe is on the order of 5 to 20 minutes with a recovery of about 60 minutes, although the precise timing is probably variable. Interestingly, the time-out is a log function instead of linear measure of activity [Ma et al 2022].

This circuit doesn’t depend on the postsynaptic S.d1 firing [Cavaccini et al 2020], which contrasts with the next LTD (long term depression) circuit which only inhibits the axon if the S.d1 projection neuron fires.

S.d1 presynaptic LTD using eCB

S.d1 self-activating LTD uses retrotransmission to inhibit its own input using eCB (endocannabiniods) as a neurotransmitter. Like the astrocyte in the previous circuit, S.d1 uses a mGlu5q receptor to trigger eCB release, but also require that S.d1 fire, as triggered by NMDA glutamate receptor. The axon receives the eCB retrotransmission with a CB1i (cannabinoid G-i inhibitory) receptor and trigger presynaptic LTD [Shen et al 2008], [Wu et al 2015]. Like the previous circuit, the timeframe seems to be on the order of 10 minutes, lasting for 30 to 60 minutes.

This circuit inhibits itself over time without using adenosine or astrocytes. In the full striatum circuit, high dopamine levels suppress this LTD suppression, meaning that dopamine inhibits the timeout [Shen et al 2008].

The next circuit adds the S.d2 path, which uses adenosine and self-activity to trigger postsynaptic LTD.

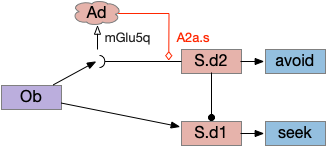

S.d2 postsynaptic LTP via A2a.s

Consider a third circuit that has the benefits of both previous circuits because it uses adenosine as a timer managed by astrocytes and is also specific to postsynaptic activity. In addition, it allows for a second action path, changing the circuit from a Go/NoGo system to a Go/Avoid action pair. This circuit uses LTP (long term potentiation) on the S.d2 striatum neurons.

When the odor first arrives, Ob activates the S.d1 path, seeking toward the odor. S.d1 is activated instead of S.d2 because of dopamine. In this simple model, the Ob itself could provide the initial dopamine like c. elegans odor-detecting neurons or the tunicate’s coronal cells or the dual glutamate and dopamine neurons in Vta (ventral tegmental area).

As time goes on, adenosine from the astrocyte builds up, which activates the S.d2 A2s.a (adenosine G-s stimulatory receptor) until it overcomes dopamine suppression and increases the S.d2 activity with LTP [Shen et al 2008]. Once S.d2 activates, it suppresses S.d1 [Chen et al 2023] and drives the avoid path.

The combination of these circuits looks like it’s precisely what the essay needs.

Simulation

In the simulation, when the animal is hunting food and finds a food odor plume, it directly seeks toward the center and eats if it find food. In the screenshot below, the animal is eating.

Satiation disables the food seek. This might sound obvious, but hunger gating of food seeking requires specific satiety circuits to any seek path that’s food specific, which means the involvement of H.l (lateral hypothalamus) and related areas like H.arc (arcuate hypothalamus) and H.pv (periventricular hypothalamus). And, of course, the simulation requires simulation code to only enable food odor seek when the animal is searching for food.

The next screenshot shows the central problem of the essay, when the animal seeks a food odor but there’s no food at the center.

Without a timeout, the animal circles the center of the food odor plume endlessly. After a timeout, the animal actively leaves the plume and avoid that specific odor until the timeout decays.

This system is somewhat complex because of the need for hysteresis. A too-simple solution with a single threshold can oscillate, because as soon as the animal starts leaving the timeout decays, which then re-enables the food-seek, which then quickly times out, repeating. Instead, the system needs to make re-enabling of the food seek more difficult after a timeout.

But that adds a secondary issue because if food seek is a lower threshold, then the sustain of seek needs to raise the threshold while the seek occurs. So, the sustain of seek needs a lower threshold than starting seek. This hysteresis and seek sustain presumably needs to be handled by the actual striatum circuit.

Discussion

I think this essay shows that using the stratum for an action timeout for food seek is a plausible application. The circuit is relatively simple and is effective, improving search by avoiding failed areas.

However, the simulation does raise some issues, particularly hysteresis problem. If the striatum does provide a timeout along these lines, it must somehow solve the hysteresis problem. While the animal is seeking, the ongoing LTP/LTD inhibition should use a high threshold to stop seeking, but once avoidance starts, there needs to be a high threshold to return to seeking to avoid oscillations between the two action paths.

Because LTD/LTP is a relatively long chemical process (minutes) internal to the neurons, as opposed to an instant switch in the simulation, the delay itself might be sufficient to solve the oscillation problem. It’s also possible that some of the more complicated parts of the circuit, such as P.ge (globus pallidus) and its feedback to the striatum or H.stn (subthalamic nucleus) might affect the sustain of seek or breaking it and so control the hysteresis problem.

The simulation also reinforced the absolute requirement that action paths need to be modulated by internal state like hunger. For the seek paths, both Hb.m and V.pt are heavily modulated by H.l and other hypothalamic hunger and satiety signals.

As expected, the simulation also illustrated the need for context information separate from the target odor. While the food odor is timed out, the animal can’t search the other odor plume because this essay’s animal can’t distinguish between the odor plumes, and therefore avoids both odors. With a long timeout and many odor plumes, this delays the food search. A future enhancement is to add context to the timeout. If the animal can timeout a specific odor plume, it can search alternatives even if the food odor itself is identical.

References

Beretta CA, Dross N, Guiterrez-Triana JA, Ryu S, Carl M. Habenula circuit development: past, present, and future. Front Neurosci. 2012 Apr 23;6:51.

Cavaccini A, Durkee C, Kofuji P, Tonini R, Araque A. Astrocyte Signaling Gates Long-Term Depression at Corticostriatal Synapses of the Direct Pathway. J Neurosci. 2020 Jul 22;40(30):5757-5768.

Chen JF, Choi DS, Cunha RA. Striatopallidal adenosine A2A receptor modulation of goal-directed behavior: Homeostatic control with cognitive flexibility. Neuropharmacology. 2023 Mar 15;226:109421.

Chen WY, Peng XL, Deng QS, Chen MJ, Du JL, Zhang BB. Role of Olfactorily Responsive Neurons in the Right Dorsal Habenula-Ventral Interpeduncular Nucleus Pathway in Food-Seeking Behaviors of Larval Zebrafish. Neuroscience. 2019 Apr 15;404:259-267.

Cui G, Jun SB, Jin X, Pham MD, Vogel SS, Lovinger DM, Costa RM. Concurrent activation of striatal direct and indirect pathways during action initiation. Nature. 2013 Feb 14;494(7436):238-42.

Derjean D, Moussaddy A, Atallah E, St-Pierre M, Auclair F, Chang S, Ren X, Zielinski B, Dubuc R. A novel neural substrate for the transformation of olfactory inputs into motor output. PLoS Biol. 2010 Dec 21;8(12):e1000567.

Gillette R, Brown JW. The Sea Slug, Pleurobranchaea californica: A Signpost Species in the Evolution of Complex Nervous Systems and Behavior. Integr Comp Biol. 2015 Dec;55(6):1058-69.

Hengenius JB, Connor EG, Crimaldi JP, Urban NN, Ermentrout GB. Olfactory navigation in the real world: Simple local search strategies for turbulent environments. J Theor Biol. 2021 May 7;516:110607.

Imamura F, Ito A, LaFever BJ. Subpopulations of Projection Neurons in the Olfactory Bulb. Front Neural Circuits. 2020 Aug 28;14:561822.

Kermen F, Franco LM, Wyatt C, Yaksi E. Neural circuits mediating olfactory-driven behavior in fish. Front Neural Circuits. 2013 Apr 11;7:62.

Ma L, Day-Cooney J, Benavides OJ, Muniak MA, Qin M, Ding JB, Mao T, Zhong H. Locomotion activates PKA through dopamine and adenosine in striatal neurons. Nature. 2022 Nov;611(7937):762-768.

Okamoto H, Cherng BW, Nakajo H, Chou MY, Kinoshita M. Habenula as the experience-dependent controlling switchboard of behavior and attention in social conflict and learning. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2021 Jun;68:36-43.

Shen W, Flajolet M, Greengard P, Surmeier DJ. Dichotomous dopaminergic control of striatal synaptic plasticity. Science. 2008 Aug 8;321(5890):848-51.

Wu YW, Kim JI, Tawfik VL, Lalchandani RR, Scherrer G, Ding JB. Input- and cell-type-specific endocannabinoid-dependent LTD in the striatum. Cell Rep. 2015 Jan 6;10(1):75-87.

Zhai S, Cui Q, Simmons DV, Surmeier DJ. Distributed dopaminergic signaling in the basal ganglia and its relationship to motor disability in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2023 Dec;83:102798.