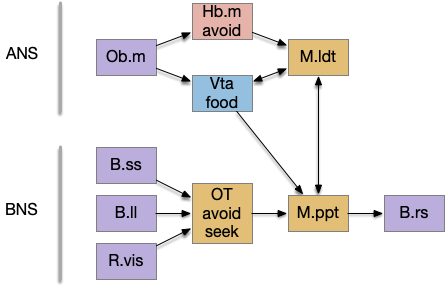

The essay 22 simulation explored a striatum model where the two decision paths competed: odor seeking vs random exploration, using dopamine to bias between exploration and seeking. This model resembled striatum theories like [Bariselli et al. 2020] that consider the stratum’s direct and indirect paths as competing between approach and avoidant actions.

Issues in essay 22 include both neuroscience divergence and simulation problems. Although the simulation is a loose functional model, that laxity isn’t infinite and it may have gone too far from the neuroscience.

Adenosine and perseveration

Seeking and foraging have a perseveration problem: the animal must eventually give up on a failed cue, or it will remain stuck forever. The give-up circuit in essay 22 uses the lateral habenula (Hb.l) to integrate search time until it reaches a threshold to give up. An alternative circuit in the stratum itself involves the indirect path (S.d2), the D2 dopamine receptor and adenosine, with a behaviorally relevant time scale.

When fast neurotransmitters are on the order of 10 milliseconds, creating a timeout on the order of a few minutes is a challenge. Two possible solutions in that timescale are long term potentiation (LTP) where “long” means about 20 minutes, and astrocyte calcium accumulation, which is also about 10 to 20 minutes.

Adenosine receptors (A2r) in the striatum indirect path (S.d2) measure broad neural activity from ATP byproducts that accumulate in the intercellular space. Over 10 minutes those A2r can produce internal calcium ion (Ca) in the astrocytes or via LTP to enhance the indirect path. Enhancing the indirect path (exploration), eventually causes a switch from the direct path (seeking) to exploration, essentially giving-up on the seeking.

Ventral striatum

Although the essay models the dorsal striatum (S.d), the ventral striatum (S.v aka nucleus accumbens) is more associated with exploration and food seeking. In particularly, the olfactory path for food seeking goes through S.v, while midbrain motor actions use S.d. In salamanders, the striatum only processes midbrain (“collo-“) thalamic inputs, while olfactory and direct senses (“lemno-“) go to the cortex [Butler 2008]. Assuming the salamander path is more primitive, the essay’s use of S.d in the model is a likely mistake.

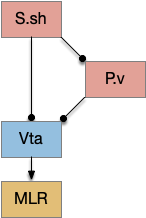

But S.v raises a new issue because S.v doesn’t use the subthalamus (H.stn) [Humphries and Prescott 2009]. Although, that model only applies to the S.v shell (S.sh) not the S.v core (S.core).

In the above diagram of a striatum shell circuit, an odor-seek path is possible through the ventral tegmental area (Vta) but there is no space for an alternate explore path.

Low dopamine and perseveration

[Rutledge et al. 2009] investigates dopamine in the context of Parkinson’s disease (PD), which exhibits perseveration as a symptom. In contrast to the essay, PD is a low dopamine condition, and adding dopamine resolves the perseveration. But that resolve is the opposite of essay 22’s dopamine model, where low dopamine resolved perseveration.

Now, it’s possible that give-up perseveration and Parkinson’s perseveration are two different symptoms, or it’s possible that the complete absence of dopamine differs from low tonic dopamine, but in either case, the essay 22 model is too simple to explain the striatum’s dopamine use.

Dopamine burst vs tonic

Dopamine in the striatum has two modes: burst and tonic. Essay 22 uses a tonic dopamine, not phasic. The striatum uses phasic dopamine to switch attention to orient to a new salient stimulus. The phasic dopamine circuit is more complicated than the tonic system because it requires coordination with acetylcholine (ACh) from the midbrain laterodorsal tegmentum (V.ldt) and pedunculopontine (V.ppt) nuclei.

A question for the essays is whether that phasic burst is primitive to the striatum, or a later addition, possibly adding an interrupt for orientation to an earlier non-interruptible striatum.

Explore semantics

The word “explore” is used differently by behavioral ecology and in reinforcement learning, despite both using foraging-like tasks. These essays have been using explore in the behavioral ecology meaning, which may cause confusion on the reinforcement learning sense. The different centers on a fixed strategy (policy) compared with changing strategies.

In behavioral ecology, foraging is literal foraging, animals browsing or hunting in a place and moving on (giving up) if the place doesn’t have food [Owen-Smith et al. 2010]. “Exploring” is moving on from an unproductive place, but the policy (strategy) remains constant because moving on is part of the strategy. The policy for when to stay and when to go [Headon et al. 1982] often follows the marginal value theorem [Charnov 1976], which specifies when the animal should move on.

In contract, reinforcement learning (RL) uses “explore” to mean changing the policy (strategy). For example, in a two-armed bandit situation (two slot machines), the RL policy is either using machine A or using machine B, or a fixed probabilistic ratio, not a timeout and give-up policy. In that context, exploring means changing the policy not merely switching machines.

[Kacelnick et al. 2011] points out that the two-choice economic model doesn’t match vertebrate animal behavior, because vertebrates use an accept-reject decision [Cisek and Hayden 2022]. So, while the two-armed bandit may be useful in economics, it’s not a natural decision model for vertebrates.

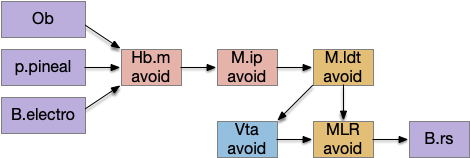

Avoidance (nicotinic receptors in M.ip)

The simulation uncovered a foraging problem, where the animal remained around an odor patch it had given up on, because the give-up strategy reverts to random search. Instead, the animal should leave the current place and only resume search when its far away.

In the diagram above, the animal remains near the abandoned food odor. The tight circles are the earlier seek before giving up, and the random path afterwards is the continued search. A better strategy would leave the green odor plume and explore other areas of the space.

As a possible circuit, the habenula (Hb.m) projects to the interpeduncular nucleus (M.ip) uses both glutamate and ACh as neurotransmitters, where ACh amplifies neural output. For low signals without ACh, the animal approaches the object, but high signals with ACh switch approach to avoidance. This avoidance switching is managed by the nicotine receptor (each) which is studied for nicotine addiction [Lee et al. 2019].

An interesting future essay might explore using nicotinic aversion to improve foraging by leaving an abandoned odor plume.

References

Bariselli S, Fobbs WC, Creed MC, Kravitz AV. A competitive model for striatal action selection. Brain Res. 2019 Jun 15;1713:70-79.

Butler, Ann. (2008). Evolution of the thalamus: A morphological and functional review. Thalamus & Related Systems. 4. 35 – 58.

Charnov, Eric L. Optimal foraging, the marginal value theorem. Theoretical population biology 9.2 (1976): 129-136.

Cisek P, Hayden BY. Neuroscience needs evolution. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2022 Feb 14;377(1844):20200518.

Headon T, Jones M, Simonon P, Strummer J (1982) Should I Stay or Should I Go. On Combat Rock. CBS Epic.

Humphries MD, Prescott TJ. The ventral basal ganglia, a selection mechanism at the crossroads of space, strategy, and reward. Prog Neurobiol. 2010 Apr;90(4):385-417.

Kacelnik A, Vasconcelos M, Monteiro T, Aw J. 2011. Darwin’s ‘tug-of-war’ vs. starlings’ ‘horse-racing’: how adaptations for sequential encounters drive simultaneous choice. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 65, 547-558.

Lee HW, Yang SH, Kim JY, Kim H. The Role of the Medial Habenula Cholinergic System in Addiction and Emotion-Associated Behaviors. Front Psychiatry. 2019 Feb 28

Owen-Smith N, Fryxell JM, Merrill EH. Foraging theory upscaled: the behavioural ecology of herbivore movement. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010 Jul 27;365(1550):2267-78.

Rutledge RB, Lazzaro SC, Lau B, Myers CE, Gluck MA, Glimcher PW. Dopaminergic drugs modulate learning rates and perseveration in Parkinson’s patients in a dynamic foraging task. J Neurosci. 2009 Dec 2