As mentioned in the previous post, sleep is often divided into circadian sleep and homeostatic sleep, although this model is an oversimplification in part because of the metabolic cycles [Borbély et al 2016]. Despite the caveats, I think starting from circadian circuits is a good start.

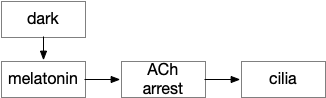

Also as mentioned previously, circadian cycles may have started as an oxidation-reduction cycle to project from oxygen’s toxicity after the Great Oxidation Event [Edgar et al 2012]. One of the early solutions is melatonin, a powerful natural antioxidant [Tosches et al 2014].

Melatonin

Melatonin exists in almost all animals except sponges. Along with its antioxidant properties, it signals for the zooplankton diel vertical migration, swimming toward the light at dusk and sinking at night [Tosches et al 2014].

In the migrating zooplankton, melatonin triggers ACh (acetylcholine) neurons, which rhythmically spike and these spikes disrupt the cilia, disorganizing them and allowing the plankton to sink.

Reptile and mammal complications

As a complication to understanding the vertebrate circuits, both reptiles and mammals have sleep requirements at odds with aquatic vertebrates. Because land temperatures change more than water temperatures, and reptiles are cold-blooded, their sleep and wake is necessarily strongly tied to temperature as well as the common light/dark connection [Rial et al 2022]. So, sleep and temperature are highly correlated, which makes the Poa (preoptic area) combination of temperature and sleep functions more reasonable than a seemingly random combination.

Mammals have the additional complication of the evolutionary nocturnal bottleneck [Rial et al 2022], meaning the simple heuristic of nighttime melatonin for sleep isn’t sufficient. The pineal melatonin is still at night for nocturnal animals [cite], and the light signaling needs to flip. Although diurnal mammals are no longer nocturnal, their clock circuitry retains the heritage of a nocturnal flip.

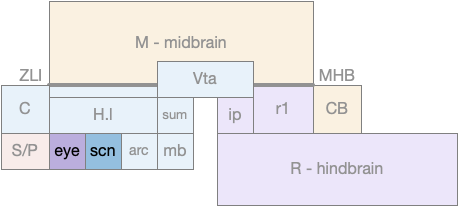

As a specific example, all non-mammalian vertebrates use the pineal gland as a circadian oscillator, not H.scn (subthalamic nucleus) [Vatine et al 2011].

Pineal gland and habenula

The pineal gland in the midbrain is the vertebrate’s main source of melatonin. Evolutionarily, the pineal gland is derived from photosensitive cells that directly convert light and dark into melatonin. In non-mammals, the pineal gland is still photosensitive. In the zebrafish, the pineal photoreceptor is still effect and entrains circadian cycles [Vatine et al 2011], and an analogous region in the non-vertebrate chordate Amphioxus provides a similar function, showing the pineal gland’s conserved function in vertebrates [Lacalli 2022].

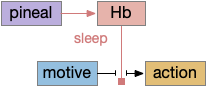

Hb.m and Hb.l (medial and lateral habenula) derive from the pineal complex, and may have originally been effectors of the pineal gland, serving a nervous function analogous to melatonin [Hikosaka 2010]. Hb.l in particular is well-suited to control neurotransmitters associated with wake, such as dopamine from Vta (ventral tegmental area), serotonin from V.dr and V.mr (dorsal and medial raphe), and norepinephrine from V.lc (locus coeruleus). Note that melatoninAs explored in essay 20, Hb.m is involved in primitive phototaxis and chemotaxis and is well-placed to inhibit those actions during sleep.

In the above diagram, a primitive habenula function is to suppress sensation, motivation and action for sleep by suppression wake-supporting neurotransmitters. Although the diagram illustrates the habenula as disconnecting motive from action, it could also disconnect sense from action, as in phototaxis or chemotaxis in Hb.m.

Hb.m includes an internal entrainable circadian clock, unlike Hb.l. The Hb.m clock is necessary for ultradian foraging. The foraging ultradian is around four hours, generally on waking. Both dopamine and NE (norepinephrine) are elevated [Wang et al 2023] and reciprocally the circadian clock is set by dopamine and NE [Salaberry and Mendoza 2022].

Some misc notes: Hb.l is required for some anesthesia (propofol) and stimulating Hb.l strongly induces NREM, and suppresses motor [Gelengen et al 2018]. Hb.l stimulus produces NREM [Goldstein 1983]. Hb.l is more active mid and late day and early night [Aizawa et al 2013] (possibly producing morning ultradian activity). Hb.l manipulation produces wake fragmentation in the wake period and sleep fragmentation in the sleep period via orexin in H.l [Gelengen et al 2018].

Cell clocks

As mentioned in the introduction, the oxidation-reduction protection may have led to the development of cellular clocks. Essentially all cells have circadian cycle in protein expression, including metabolic and detoxification cells in the liver, heart, kidneys and digestion [Dibner et al 2010], even including gut bioflora. The clocks are synchronized by multiple signals, including feeding patterns, but most studied by light.

For example, dopamine is under clock control and is modulated by melatonin [Ashton and Jagannath 2020]. In S.v (ventrial striatum aka nucleus accumbens) dopamine is at a daily low at night. DAT (dopamine transporter), affected by cocaine, is regulated by clock genes [Alsonso et al 2021], possibly under control of astrocytes. Dopamine is particularly tonically high in early morning before eating with an ultradian cycle of about four hours. Two four-ish hour dopamine cycles are known: the FEO (food entrainable oscillator), which produces pre-feeding activity [Dibner et al 2010], and MASCO (methamphetamine-sensitive circadian oscillatory) [Tataroglu et al 2006], which may be the same system.

The retina itself is under circadian control, modulated by dopamine and D2i (inhibitory Gi-coupled dopamine receptor) [Yujinovsky et al 2006], including in frogs [Cahill and Besharse 1991].

And astrocytes in S.v are under circadian cell clock control [Becker-Krail et al 2022]. Astrocytes are well-placed to manage sleep because they have widespread connections to many synapses and are connected to other astrocytes with gap junctions, allowing for integration over time and space and widespread broadcast signaling.

H.scn circadian entrainment

The circadian system has three distinct components that can either work on their own or work together:

- Cell clocks

- Light / dark photoreceptors or feeding signals and behavior

- Entraining the cell clock to the signal (zeitgeber)

If the eye area of the mollusk sea hare is lesioned, circadian entrainment is eliminated, but because of other photoreceptors, the animal still follows light and dark cycles as long as the light changes. The deficit is only exposed when the lesioned mollusks are placed under continual dark [Vorster et al 2014], [Newcomb et al 2014]. Similarly, in zebrafish many cells are photoreceptive without entraining the cellular clocks.

Mammals use H.scn (suprachiasmatic nucleus) to coordinate circadian cellular clocks. The H.scn name is important, but it’s located above the optic crossing (suprachiasmatic) and developmentally the retina develops from the hypothalamus adjacent to H.scn.

The diagram above shows the rough location of the retina development area and H.scn, which both develop from the hypothalamus. A primitive eye with only a few photoreceptors would have been part of the hypothalamus, and like the mollusk the photoreceptor would be near the clock entrainment circuit that became H.scn.

The H.scn clock signal is somewhat indirect, with an interim projection to H.scz to H.dm (dorsomedial hypothalamus) and finally to H.l (lateral hypothalamus) for wake and Po.vl (ventrolateral preoptic area) for sleep. H.scn uses dopamine from Vta as part of its synchronization [Grippo et al 2017].

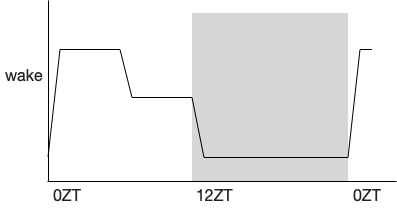

Ultradian DA – morning foraging

The sleep / wake cycle has an additional boost during normal foraging times such as immediately after waking. In the subjective morning (dark for rodents), wake is encouraged, homeostatic sleep is suppressed, and dopamine levels are higher. After the foraging boost ends, but still in the wake period, tonic dopamine levels drop and the animals take more frequent naps. This hut radian boost of about four hours affects learning and behavior as well as modulating drug abuse [Ruby et al 2013].

Because this ultradian foraging boots wake and suppresses sleep significantly, studies that stimulate or inhibit sleep and wake can specifically affect the ultradian boost without affecting other sleep / wake periods. So it’s very important to look at the hourly effects because the experimental modulation might reduce the foraging boost specifically, but a summary might show a general sleep increase.

H.scn circadian entrainment uses dopamine. DA from either Vta [Grippo et al 2017], [Tang et al 2022] and/or H.sum (supramammillary nucleus) [Luo et al 2018] can entrain food circadian cycles. Note that since the dopamine “A10” area extends beyond the Vta to include H.sum and M.pag.v on opposite ends of the Vta, these studies may be reporting the same area.

As mentioned above, there are also the food entrained oscillator [Liu et al 2012], [Gallardo et al 2014], [Pendergast and Yamazaki 2019], [Ashton and Jagannath 2020], and the meth-sensitive oscillator [Tataroglu et al 2006], which are also dopamine related and may be part of the same system.

Neurotransmitters and peptides

The inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA is associated with sleep, and many sleep drugs are GABA stimulants. GABA neurons in Snr (substantia nigra pars reticulata), H.zi (zona incerta), Vta, and Po.vl are all associated with sleep. As mentioned above GABA from mitochondria and in Hydra are used as a sleep promoting neurotransmitter.

While GABA is associated with sleep, other major neurotransmitters like NE, DA, 5HT (serotonin), ACh (acetylcholine) and histamine are associated with wake maintenance of the execution of wakefulness. As discussed in the previous post, ongoing actions need to suppress sleep. NE, DA, and 5HT are all maintain wake while the animal is active and drop when the animal is winding down activity to sleep. Cortical wake requires activity in ACh-rich area in Ppt (pedunculopontine nucleus), P.ldt (laterodorsal tegmental nucleus), and P.bf (basal forebrain).

Produced by H.l, orexin (aka hypocretin) appears to be a wake-maintenance peptide since removal of orexin produces narcolepsy. H.l orexin projects to essentially all of the other wake-maintaining neurotransmitters, including NE, DA, 5HT and ACh. Orexin is slow, waking after tens of seconds, while stimulating V.lc NE is around two seconds [Yamaguchi et al 2018]. On counterargument is that orexin can ramp later in the day [Grady et al 2006], [Mogavero et al 2023], which would suggest that it’s not part of the ultradian foraging system, although it’s also highly tied to foraging. (Suggesting I need to read more articles to see if the contradiction has been resolved.)

Although orexin is the most dramatic of H.l wake, H.l also includes wake and sleep producing GABA and glutamate neurons that may be even more important for wake, independent of the orexin function. Unfortunately, H.l is complex enough that the different functions haven’t been fully pulled apart.

Adenosine is a sleep-promoting molecule derived from the energy molecule ATP, and has extensive receptor throughout the brain, notable in the striatum. Because it’s a product of ATP, it measures local neural activity and possibly sleep need. Its measurement of global brain activity for homeostatic sleep seems more questionable, but adenosine does accumulate throughout the wake period in P.bf [Porkka-Heiskanan et al 2000].

Inflammation peptides like IL-1β are also sleep-promoting [Imeri and Opp 2009]. In addition to their inflammation-related sleep, they seem to be part of normal homeostatic sleep signaling. In Drosophila sleep-need astrocytes produce IL-1β as a signaling peptide [Blum et al 2021]. In zebrafish, sleep deprivation correlates with immune signaling [Williams et al 2007].

Next: ignition and maintenance circuits

After this general discussion on sleep wake, the next post will cover some of the specific sleep and wake circuits, particularly those associated with wake ignition, wake maintenance and sleep maintenance.

References

Aizawa H, Cui W, Tanaka K, Okamoto H. Hyperactivation of the habenula as a link between depression and sleep disturbance. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013 Dec 10;7:826.

Ashton A, Jagannath A. Disrupted Sleep and Circadian Rhythms in Schizophrenia and Their Interaction With Dopamine Signaling. Front Neurosci. 2020 Jun 23;14:636.

Becker-Krail DD, Walker WH 2nd, Nelson RJ. The Ventral Tegmental Area and Nucleus Accumbens as Circadian Oscillators: Implications for Drug Abuse and Substance Use Disorders. Front Physiol. 2022 Apr 27;13:886704.

Blum ID, Keleş MF, Baz ES, Han E, Park K, Luu S, Issa H, Brown M, Ho MCW, Tabuchi M, Liu S, Wu MN. Astroglial Calcium Signaling Encodes Sleep Need in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2021 Jan 11;31(1):150-162.e7.

Borbély AA, Daan S, Wirz-Justice A, Deboer T. The two-process model of sleep regulation: a reappraisal. J Sleep Res. 2016 Apr;25(2):131-43.

Cahill GM, Besharse JC. Resetting the circadian clock in cultured Xenopus eyecups: regulation of retinal melatonin rhythms by light and D2 dopamine receptors. J Neurosci. 1991 Oct;11(10):2959-71.

Dibner, C., Schibler, U., & Albrecht, U. (2010). The mammalian circadian timing system: organization and coordination of central and peripheral clocks. Annual review of physiology, 72, 517-549.

Edgar RS, Green EW, Zhao Y, van Ooijen G, Olmedo M, Qin X, Xu Y, Pan M, Valekunja UK, Feeney KA, Maywood ES, Hastings MH, Baliga NS, Merrow M, Millar AJ, Johnson CH, Kyriacou CP, O’Neill JS, Reddy AB. Peroxiredoxins are conserved markers of circadian rhythms. Nature. 2012 May 16;485(7399):459-64.

Gallardo CM, Darvas M, Oviatt M, Chang CH, Michalik M, Huddy TF, Meyer EE, Shuster SA, Aguayo A, Hill EM, Kiani K, Ikpeazu J, Martinez JS, Purpura M, Smit AN, Patton DF, Mistlberger RE, Palmiter RD, Steele AD. Dopamine receptor 1 neurons in the dorsal striatum regulate food anticipatory circadian activity rhythms in mice. Elife. 2014 Sep 12;3:e03781.

Gelegen C, Miracca G, Ran MZ, Harding EC, Ye Z, Yu X, Tossell K, Houston CM, Yustos R, Hawkins ED, Vyssotski AL, Dong HL, Wisden W, Franks NP. Excitatory Pathways from the Lateral Habenula Enable Propofol-Induced Sedation. Curr Biol. 2018 Feb 19;28(4):580-587.e5.

Goldstein, R. (1983). A GABAergic habenulo-raphe pathway mediation of the hypnogenic effects of vasotocin in cat. Neuroscience 10, 941–945.

Grady, S. P., Nishino, S., Czeisler, C. A., Hepner, D., & Scammell, T. E. (2006). Diurnal variation in CSF orexin-A in healthy male subjects. Sleep, 29(3), 295-297.

Grippo RM, Purohit AM, Zhang Q, Zweifel LS, Güler AD. Direct Midbrain Dopamine Input to the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus Accelerates Circadian Entrainment. Curr Biol. 2017 Aug 21;27(16):2465-2475.e3.

Hikosaka O. The habenula: from stress evasion to value-based decision-making. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010 Jul;11(7):503-13.

Lacalli T. An evolutionary perspective on chordate brain organization and function: insights from amphioxus, and the problem of sentience. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2022 Feb 14;377(1844):20200520.

Liu YY, Liu TY, Qu WM, Hong ZY, Urade Y, and Huang ZL (2012) Dopamine is involved in food-anticipatory activity in mice. J Biol Rhythms 27:398–409.

Luo YJ, Ge J, Chen ZK, Liu ZL, Lazarus M, Qu WM, Huang ZL, Li YD. Ventral pallidal glutamatergic neurons regulate wakefulness and emotion through separated projections. iScience. 2023 Aug 5;26(8):107385.

Mogavero MP, Godos J, Grosso G, Caraci F, Ferri R. Rethinking the Role of Orexin in the Regulation of REM Sleep and Appetite. Nutrients. 2023 Aug 22;15(17):3679.

Newcomb JM, Kirouac LE, Naimie AA, Bixby KA, Lee C, Malanga S, Raubach M, Watson WH 3rd. Circadian rhythms of crawling and swimming in the nudibranch mollusc Melibe leonina. Biol Bull. 2014 Dec;227(3):263-73.

Pendergast JS, Yamazaki S. The Mysterious Food-Entrainable Oscillator: Insights from Mutant and Engineered Mouse Models. J Biol Rhythms. 2018 Oct;33(5):458-474.

Porkka-Heiskanen T, Strecker RE, McCarley RW. Brain site-specificity of extracellular adenosine concentration changes during sleep deprivation and spontaneous sleep: an in vivo microdialysis study. Neuroscience. 2000;99(3):507-17.

Rial RV, Canellas F, Akaârir M, Rubiño JA, Barceló P, Martín A, Gamundí A, Nicolau MC. The Birth of the Mammalian Sleep. Biology (Basel). 2022 May 11;11(5):734. doi: 10.3390/biology11050734.

Ruby NF, Hwang CE, Wessells C, Fernandez F, Zhang P, Sapolsky R, Heller HC. Hippocampal-dependent learning requires a functional circadian system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Oct 7;105(40):15593-8.

Salaberry NL, Mendoza J. The circadian clock in the mouse habenula is set by catecholamines. Cell Tissue Res. 2022 Feb;387(2):261-274.

Tang Q, Assali DR, Güler AD, Steele AD. Dopamine systems and biological rhythms: Let’s get a move on. Front Integr Neurosci. 2022 Jul 27;16:957193.

Tataroglu O, Davidson AJ, Benvenuto LJ, Menaker M. The methamphetamine-sensitive circadian oscillator (MASCO) in mice. J Biol Rhythms. 2006 Jun;21(3):185-94.

Tosches MA, Bucher D, Vopalensky P, Arendt D. Melatonin signaling controls circadian swimming behavior in marine zooplankton. Cell. 2014 Sep 25;159(1):46-57.

Vatine G, Vallone D, Gothilf Y, Foulkes NS. It’s time to swim! Zebrafish and the circadian clock. FEBS Lett. 2011 May 20;585(10):1485-94.

Vorster AP, Krishnan HC, Cirelli C, Lyons LC. Characterization of sleep in Aplysia californica. Sleep. 2014 Sep 1;37(9):1453-63.

Wang F, Wang W, Gu S, Qi D, Smith NA, Peng W, Dong W, Yuan J, Zhao B, Mao Y, Cao P, Lu QR, Shapiro LA, Yi SS, Wu E, Huang JH. Distinct astrocytic modulatory roles in sensory transmission during sleep, wakefulness, and arousal states in freely moving mice. Nat Commun. 2023 Apr 17;14(1):2186.

Yamaguchi H, Hopf FW, Li SB, de Lecea L. In vivo cell type-specific CRISPR knockdown of dopamine beta hydroxylase reduces locus coeruleus evoked wakefulness. Nat Commun. 2018 Dec 6;9(1):5211.

Yujnovsky I, Hirayama J, Doi M, Borrelli E, Sassone-Corsi P. Signaling mediated by the dopamine D2 receptor potentiates circadian regulation by CLOCK:BMAL1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Apr 18;103(16):6386-91.

Williams JA, Sathyanarayanan S, Hendricks JC, Sehgal A. Interaction between sleep and the immune response in Drosophila: a role for the NFkappaB relish. Sleep. 2007 Apr;30(4):389-400.