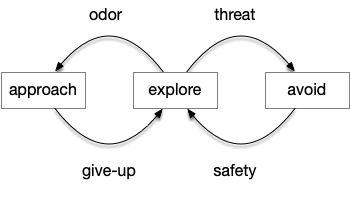

The original impetus for this sleep essay was the idea that the basal ganglia could best be understood as a sleep and wake circuit [Kazmierczak and Nicola 2022]. After reviewing the rest of the brainstem sleep circuitry, it’s time to tackle the original problem.

Snr as a sleep/wake gate

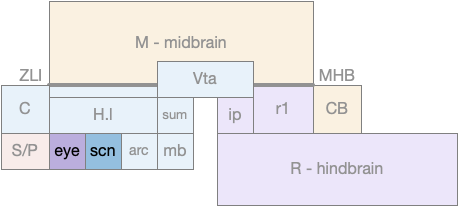

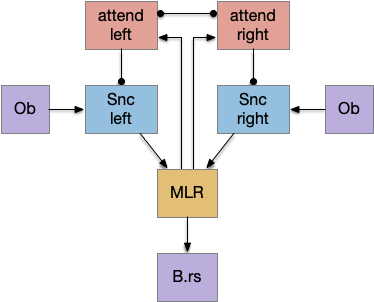

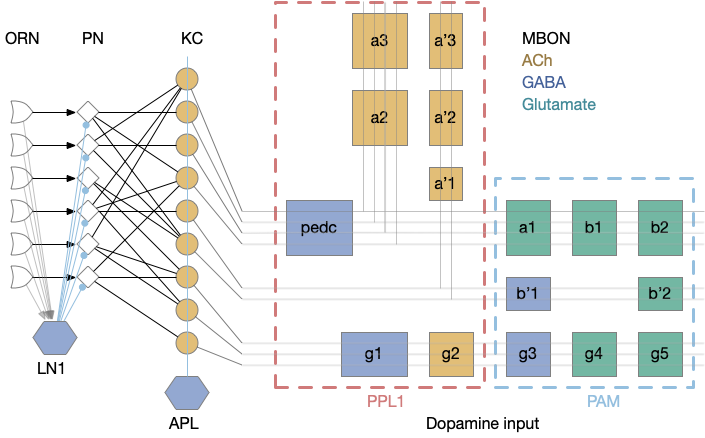

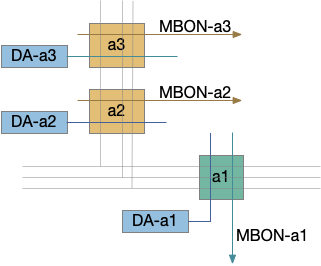

Snr (substantia nigra pars reticulata) is the output node of the basal ganglia. It’s a set of GABA neurons that tonically suppress the majority of all brainstem motor areas including MLR (midbrain locomotor region), OT (optic tectum), and R.rs (hindbrain reticulospinal motor command) with corollary discharge to the thalamus. Snr can inhibit initiation of eating and motion [Rossi et al 2016], but don’t disrupt ongoing actions [Liu et al 2018]. Disruption of Snr can cause hyperactivity and insomnia [Geraschenko et al 2006]. The caudal Snr derives from hindbrain r1 (rhombomere r1 near the midbrain-hindbrain boundary) [Achim et al 2012], [Lahti et al 2015], [Partanen and Achim 2022], suggesting it may be evolutionarily old, possibly older than other basal ganglia regions.

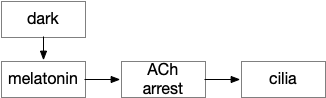

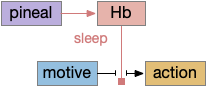

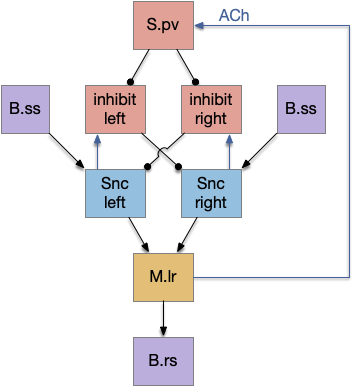

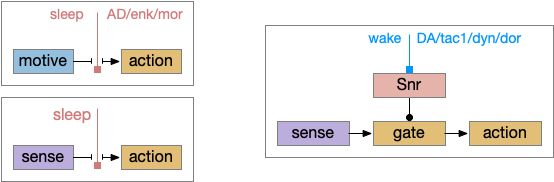

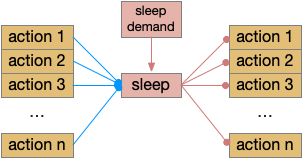

As described in part 1 this essay, sleep suppresses senses, motivation and action. To implement this suppression, sleep could disconnect senses and motivation neurons from action neurons. In the above diagram, the gate is conceptual. The circuit could also inhibit the sense or action nodes directly instead of requiring specific gating neurons. This gating architecture has the advantage of simplicity because the sleep circuit can be localized in the gate, while the senses and actions can be mostly free of sleep circuitry.

As a preview, sleep neurotransmitters and peptides in BG (basal ganglia) include AD (adenosine), enk (enkephalin), MOR (μ-opioid receptor), and wake neurotransmitters include DA (dopamine), tac1 (tachykinin 1 aka neurokinin 1 aka substance P), dyn (dynorphin), and DOR (δ-opioid receptor).

If the vertebrate brain follows this architecture, Snr is well-placed to control that gate. Snr.m (medial Snr) projections have many collaterals to distinct motor areas and suppressing the wake-promoting areas covered earlier in this essay, which suggests widespread suppression as opposed to fine-grained control.

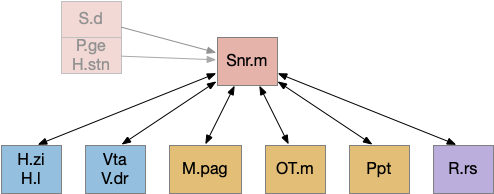

As the above diagram illustrates, despite its description as basal ganglia output, 60% of the gad2 (genetic marker), Snr.m inputs are outside of the basal ganglia, particularly from the midbrain (30%) and hypothalamus (10%) [Liu et al 2020]. Snr.m has two independent neuron types marked by gad2 and pv (parvalbumin), which are topographically organized with gad2 in Snr.m and pv in Snr.l (lateral Snr). While Snr.l.pv seems to be strictly motor related, Snr.m.gad2 are sleep related [Liu et al 2020]. However, [Lai et al 2021] reports Snr.l as sleep related.

Snr’s widespread motor and motivation connectivity suggests a possible primitive role in sleep. Sleep needs to suppress all actions, but any ongoing action needs to suppress sleep, because an animal shouldn’t fall asleep while eating or moving. It seems plausible that a primitive proto-vertebrate could have used Snr for sleep regulation without needing the rest of the basal ganglia.

Because astrocytes can integrate inputs spatially and temporally and are associated with sleep, it’s plausible that Snr astrocyte would be involved in this circuit. Interestingly Snr astrocytes are sensitive to dopamine and become hyperactive in the absence of dopamine [Bosson et al 2015] and are sensitive to glutamate from H.stn [Barat et al 2015].

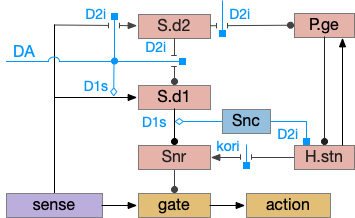

Dopamine D2.i sleep / wake circuit

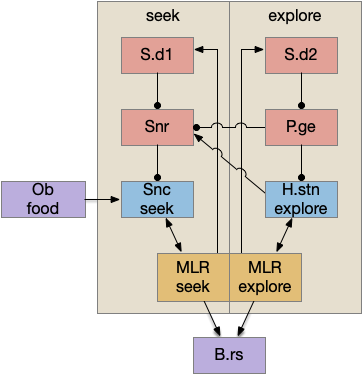

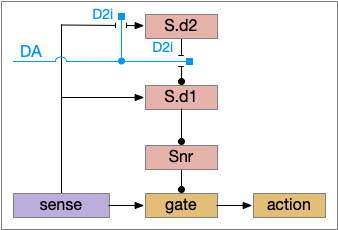

Although the independent Snr circuit is a functional sleep / wake gating circuit, it tonically inhibits the sense to action circuit, adding noise. An improvement to the circuit enables the gate when a signal is available, using the striatum to selectively open the gate. This circuit uses dopamine to open and close the gate. High dopamine is a wake signal and low dopamine is a sleep signal.

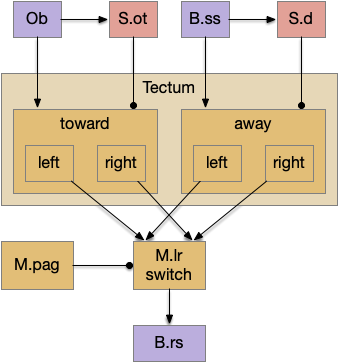

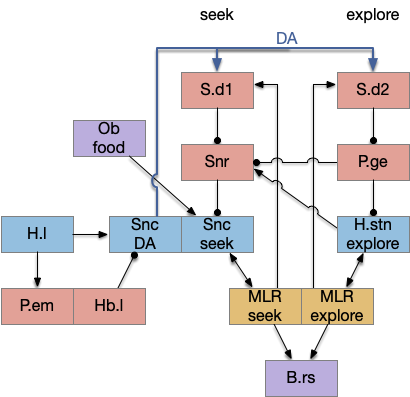

In the above diagram, Snr and S.d2 (D2.i associated striatum projection neurons) are sleep-promoting regions and S.d1 (D1.s associated striatum projection neurons) is a wake-promoting region. D2.i (inhibitory Gi-protein dopamine receptor) disconnects inputs, as opposed to inhibiting a neuron directly. When DA is available, S.d2 is disconnected, and S.d1 inhibits Snr, opening the gate. When DA is low, S.d2 is active, which inhibits S.d1, disinhibiting Snr, closing the gate and producing sleep. The D2i between S.d2 and S.d1 is from [Dobbs et al 2016].

The idea of the circuit is that the sense signal disinhibits itself during wake, but sleep prevents sense from disinhibiting itself. The minimal system only requires D2i circuits [Oishi et al 2017]. Wake enables the gate, and sleep disables the gate. Although I’ll cover D1s later, D2i is more fundamental because disabling D1s can be reversed by sufficient arousal, but disabling D2i can’t [Kazmierczak and Nicola 2022].

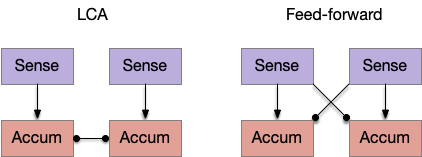

Note the diagram is somewhat incorrect, because direct S.d2 to S.d1 connection is weak [Tepper 2008]. Instead, S.d2 GABA inhibits S.d1 input at distal dendrites as opposed to inhibiting the neuron soma itself.

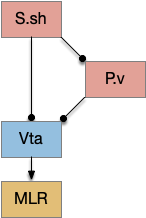

P.v ventral pallidum and S.core

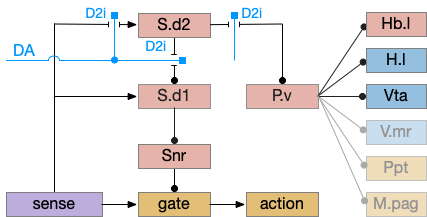

While S.d2 neurons in model above suppresses motor for sleep, S.d2 in S.core (ventral striatum core aka nucleus accumbens) can produce sleep pressure by inhibiting the wake supporting P.v (ventral pallidum) [Oishi et al 2017]. P.v is a tonically active, wake-promoting nucleus, primarily inhibiting sleep areas or disinhibiting wake areas.

P.v fill a similar wake-promoting role as S.d1, but unlike S.d1 it’s tonically active and affects the motivation loop of H.l, Hb.l, and Vta instead of gating sense from action. Where P.v supports general wake, S.d1 supports specific wake for an action. Like the previous basal ganglia sub-circuit, this sub-circuit only requires D2i receptors.

P.v promotes wake by inhibiting Hb.l sleep-producing system [Li et al 2023]. It also promotes wake through Vta by disinhibiting GABA interneurons [Li et al 2021]. (It could also disinhibit H.l orexin but I don’t have a reference).

In the model above, stimulating S.d2 inhibits wake-producing P.v, which disinhibits sleep-producing areas like Hb.l and inhibits wake-producing areas like H.l and Vta through GABA interneurons. Conversely, stimulating the D2i receptor by high DA inhibits S.d2, which disinhibits Pv, allowing it so promote wake. Disabling the D2i receptor activates S.d2, promoting sleep even with high dopamine [Qu et al 2010].

Note that S.d1 also connects to P.v and can produce wake [Zhang et al 2023]. P.v has multiple sub-populations with opposing functions. For example, it has both a hedonic hot spot for liked food and a cold spot for disliked food [Castro et al 2015]. For the sake of simplicity the diagram only shows a sleep-promoting path through S.d2, but there may be a wake-promoting path through S.d2 to an opposing P.v subpopulation.

D1s – stimulator dopamine receptors

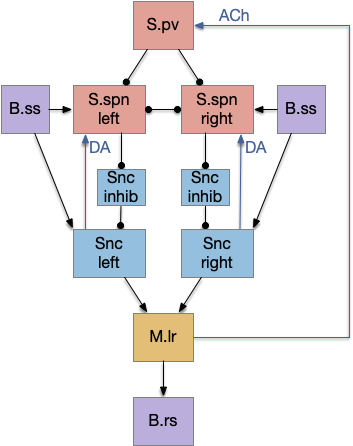

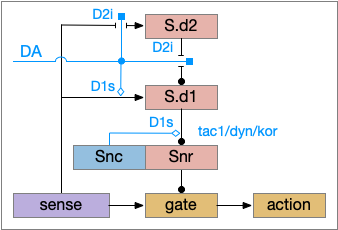

Although using only D2i as a mode switch to the sleep path is functional, it can be improved by also enhancing the wake path with D1s (stimulatory Gs-coupled dopamine receptor).

The improved circuit works exactly like the D2i-only circuit but enhances the wake path when DA is available. Dopamine boosts both the signals from the sense to S.d1 and the signal from S.d1 to Snr [Salvatore 2024], [Kliem 2007], [Rice and Patel 2015]. When dopamine is available, it boots the sense to S.d1 signal with D1s, which more strongly disinhibits the gate by inhibiting Snr, which is also boosted by D1s.

The D1s in Snr and dopamine may be more important for motor suppression than dopamine in the striatum [Salvatore 2024]. In Parkinson’s disease and also normal aging, bradykinesia (slow movement) correlates with dopamine in Snr more closely than dopamine in the striatum. Motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease don’t generally occur until striatal dopamine is reduced by 80%, but the effect on Snr is more immediate with only a small drop of dopamine.

Note that the Snc (substantia nigra pars compacta) to Snr dopamine comes from somatodendritic broadcast, not from an axon synapse. Snc dendrites in Snr produce dopamine to enhance the S.d1 to Snr connection.

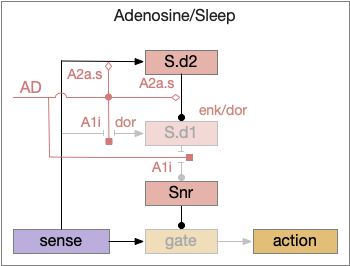

Although the previous diagrams show the basic logic of the circuit, the basal ganglia use adenosine as a sleep-producing neurotransmitter, competing with dopamine.

Adenosine in striatum sleep

Adenosine is a product of the energy molecule ATP and is produced by neural activity, and also as a astrocyte transmission molecule. Although adenosine can accumulate in a circadian manner, particularly in P.bf (basal forebrain), it’s typically a shorter term sleep pressure. Caffeine is wake promoting by suppressing adenosine receptors.

Dopamine and adenosine are paired, opposing neurotransmitters in the basal ganglia: dopamine produces wake and adenosine promotes sleep. As an opposing signal to dopamine, the adenosine circuit is a flip version of the dopamine circuit.

When adenosine is active in the above circuit, it cuts off S.d1 input and output and enhances S.d2’s suppression of S.d1. With S.d2 fully suppressed, Snr is free to suppress the gate and therefore suppress sleeping action.

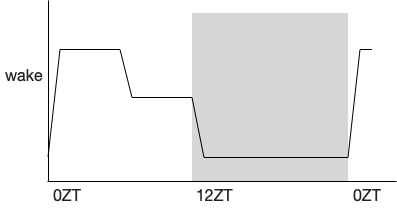

Since adenosine is low in the morning, sleep is suppressed, which is enhanced by high ultradian morning dopamine. If A2a.s (stimulating Gs-coupled adenosine receptor) are stimulated in the striatum, the animal is more likely to sleep even in the morning [Yuan et al 2017], specifically in S.core not S.sh (ventral striatum shell aka nucleus accumbens) [Oishi et al 2017].

The dual signal system allows for interesting combinations at the boundary between sleep and wake. If adenosine is high with sleep pressing, then a large amount of dopamine motivation is required to continue wake. In fact, sleep deprivation down regulates D2i receptors, moving from the neuron membrane to the interior [Volkow et al 2012], which tips the balance toward sleep by diminishing the D2i-mediated wake signal. Caffeine inhibits both the A1i (inhibitory Gi-coupled adenosine receptor) and A2a.s receptors, tipping the balance to dopamine wake.

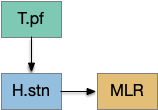

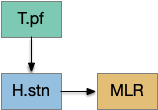

Dorsal striatum indirect path

The full S.d (dorsal striatum) path includes an indirect path, but this path may be more related to pure motor control, not sleep. As mentioned above, Snr divides into two populations Snr.l with pv neurons and Snr.m with gad2 neurons, and the Snr.l neurons are motor related, not sleep related [Liu et al 2020]. Similarly, the indirect path including P.ge (external globus pallidus) and H.stn (sub thalamic nucleus) may not be sleep related. Nevertheless, I’ll include it here, in case it is sleep related.

Note that both P.ge and H.stn are tonically active, and they oscillate together at beta frequencies (roughly 10hz), which suppresses action. An excessive beta oscillation in this P.ge and H.stn circuit is a Parkinson’s disease symptom that suppresses motion and can also interrupt sleep. D2i receptors in H.stn mean that dopamine suppresses H.stn output [Shen et al 2012].

One significant experiment showed that lesioning P.ge increased wake by 40%, particularly eliminating normal circadian night-time sleep, replacing it with day-time like napping [Qiu et al 2016], which would suggest that P.ge is a major sleep center like Po.vl (ventrolateral preoptic area) [Vetrivelan et al 2010]. Note that this analysis would suggest that my basal ganglia sleep diagram is entirely wrong, because P.ge as a sleep center is basically incompatible with its position in the circuit.

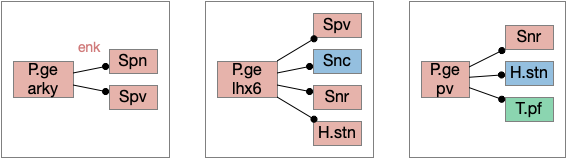

P.ge – external globus pallidus

Lesioning P.ge increases wake by 40%, almost entirely eliminating circadian sleep [Qiu et al 2016]. However, this produces hyperactive chewing, weight loss, abnormal motor behavior and death in 3-4 weeks [Vetrivelan et al 2010]. Other manipulations of P.ge produce hyperactivity, abnormal movement, and odd stereotypical behavior [Gittis et al 2014]. So, it’s unclear to me that P.ge is a sleep center, but removing P.ge produces excessive action which then suppresses sleep.

In addition, P.ge is a heterogenous area with at least three major cell types with distinct projections and roles. Arkypallidal neurons project strongly and exclusively to the striatum. Lhx6 neurons project strongly to Snc and to some areas of H.stn, excluding the center. Pv neurons project to all of H.stn and also to T.pf (parafascical thalamus) [Gittis et al 2014].

With three projection types, it’s possible that they have entirely separate functions. For example, the lhx6 projections are functionally compatible with a sleep promoting role, and lhx6 neurons in H.zi (zona incerta) are sleep promoting [Liu et al 2017].

References

Achim K, Peltopuro P, Lahti L, Li J, Salminen M, Partanen J. Distinct developmental origins and regulatory mechanisms for GABAergic neurons associated with dopaminergic nuclei in the ventral mesodiencephalic region. Development. 2012 Jul;139(13):2360-70.

Barat E, Boisseau S, Bouyssières C, Appaix F, Savasta M, Albrieux M. Subthalamic nucleus electrical stimulation modulates calcium activity of nigral astrocytes. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e41793.

Bosson A, Boisseau S, Buisson A, Savasta M, Albrieux M. Disruption of dopaminergic transmission remodels tripartite synapse morphology and astrocytic calcium activity within substantia nigra pars reticulata. Glia. 2015 Apr;63(4):673-83.

Castro DC, Cole SL, Berridge KC. Lateral hypothalamus, nucleus accumbens, and ventral pallidum roles in eating and hunger: interactions between homeostatic and reward circuitry. Front Syst Neurosci. 2015 Jun 15;9:90.

Dobbs LK, Kaplan AR, Lemos JC, Matsui A, Rubinstein M, Alvarez VA. Dopamine Regulation of Lateral Inhibition between Striatal Neurons Gates the Stimulant Actions of Cocaine. Neuron. 2016 Jun 1;90(5):1100-13.

Gerashchenko D, Blanco-Centurion CA, Miller JD, Shiromani PJ. Insomnia following hypocretin2-saporin lesions of the substantia nigra. Neuroscience. 2006;137(1):29-36.

Gittis AH, Berke JD, Bevan MD, Chan CS, Mallet N, Morrow MM, Schmidt R. New roles for the external globus pallidus in basal ganglia circuits and behavior. J Neurosci. 2014 Nov 12;34(46):15178-83.

Kaźmierczak M, Nicola SM. The Arousal-motor Hypothesis of Dopamine Function: Evidence that Dopamine Facilitates Reward Seeking in Part by Maintaining Arousal. Neuroscience. 2022 Sep 1;499:64-103.

Kliem MA, Maidment NT, Ackerson LC, Chen S, Smith Y, Wichmann T. Activation of nigral and pallidal dopamine D1-like receptors modulates basal ganglia outflow in monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 2007 Sep;98(3):1489-500.

Lahti L, Haugas M, Tikker L, Airavaara M, Voutilainen MH, Anttila J, Kumar S, Inkinen C, Salminen M, Partanen J. Differentiation and molecular heterogeneity of inhibitory and excitatory neurons associated with midbrain dopaminergic nuclei. Development. 2016 Feb 1;143(3):516-29.

Lai YY, Kodama T, Hsieh KC, Nguyen D, Siegel JM. Substantia nigra pars reticulata-mediated sleep and motor activity regulation. Sleep. 2021 Jan 21;44(1):zsaa151.

Li YD, Luo YJ, Xu W, Ge J, Cherasse Y, Wang YQ, Lazarus M, Qu WM, Huang ZL. Ventral pallidal GABAergic neurons control wakefulness associated with motivation through the ventral tegmental pathway. Mol Psychiatry. 2021 Jul;26(7):2912-2928.

Li Y, Zhang X, Li Y, Li Y, Xu H. Activation of Ventral Pallidum CaMKIIa-Expressing Neurons Promotes Wakefulness. Neurochem Res. 2023 Aug;48(8):2502-2513.

Liu K, Kim J, Kim DW, Zhang YS, Bao H, Denaxa M, Lim SA, Kim E, Liu C, Wickersham IR, Pachnis V, Hattar S, Song J, Brown SP, Blackshaw S. Lhx6-positive GABA-releasing neurons of the zona incerta promote sleep. Nature. 2017 Aug 31;548(7669):582-587. doi: 10.1038/nature23663. Epub 2017 Aug 23.

Liu, D., Ma, C., Zheng, W., Yao, Y., & Dan, Y. (2018). Sleep and motor control by a basal ganglia circuit. BioRxiv, 405324.

Liu D, Li W, Ma C, Zheng W, Yao Y, Tso CF, Zhong P, Chen X, Song JH, Choi W, Paik SB, Han H, Dan Y. A common hub for sleep and motor control in the substantia nigra. Science. 2020 Jan 24;367(6476):440-445.

Oishi Y, Suzuki Y, Takahashi K, Yonezawa T, Kanda T, Takata Y, Cherasse Y, Lazarus M. Activation of ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons produces wakefulness through dopamine D2-like receptors in mice. Brain Struct Funct. 2017 Aug;222(6):2907-2915.

Partanen J, Achim K. Neurons gating behavior-developmental, molecular and functional features of neurons in the Substantia Nigra pars reticulata. Front Neurosci. 2022 Sep 6;16:976209.

Qiu MH, Yao QL, Vetrivelan R, Chen MC, Lu J. Nigrostriatal Dopamine Acting on Globus Pallidus Regulates Sleep. Cereb Cortex. 2016 Apr;26(4):1430-9.

Qu WM, Xu XH, Yan MM, Wang YQ, Urade Y, Huang ZL. Essential role of dopamine D2 receptor in the maintenance of wakefulness, but not in homeostatic regulation of sleep, in mice. J Neurosci. 2010 Mar 24;30(12):4382-9.

Rice ME, Patel JC. Somatodendritic dopamine release: recent mechanistic insights. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015 Jul 5;370(1672):20140185.

Rossi MA, Li HE, Lu D, Kim IH, Bartholomew RA, Gaidis E, Barter JW, Kim N, Cai MT, Soderling SH, Yin HH. A GABAergic nigrotectal pathway for coordination of drinking behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2016 May;19(5):742-748.

Salvatore MF. Dopamine Signaling in Substantia Nigra and Its Impact on Locomotor Function-Not a New Concept, but Neglected Reality. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jan 17;25(2):1131.

Shen KZ, Johnson SW. Regulation of polysynaptic subthalamonigral transmission by D2, D3 and D4 dopamine receptors in rat brain slices. J Physiol. 2012 May 15;590(10):2273-84.

Tepper JM, Wilson CJ, Koós T. Feedforward and feedback inhibition in neostriatal GABAergic spiny neurons. Brain Res Rev. 2008 Aug;58(2):272-81.

Vetrivelan R, Qiu MH, Chang C, Lu J. Role of Basal Ganglia in sleep-wake regulation: neural circuitry and clinical significance. Front Neuroanat. 2010 Nov 23;4:145.

Volkow ND, Tomasi D, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J, Benveniste H, Kim R, Thanos PK, Ferré S. Evidence that sleep deprivation downregulates dopamine D2R in ventral striatum in the human brain. J Neurosci. 2012 May 9;32(19):6711-7.

Yuan XS, Wang L, Dong H, Qu WM, Yang SR, Cherasse Y, Lazarus M, Schiffmann SN, d’Exaerde AK, Li RX, Huang ZL. Striatal adenosine A2Areceptor neurons control active-period sleep via parvalbumin neurons in external globus pallidus. Elife. 2017 Oct 12;6:e29055.

Zhang J, Peng Y, Liu C, Zhang Y, Liang X, Yuan C, Shi W, Zhang Y. Dopamine D1-receptor-expressing pathway from the nucleus accumbens to ventral pallidum-mediated sevoflurane anesthesia in mice. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2023 Nov;29(11):3364-3377.