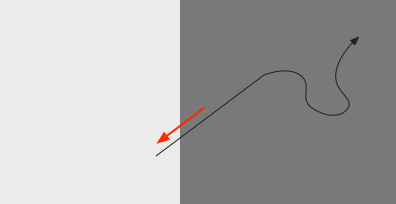

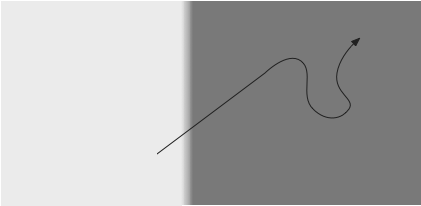

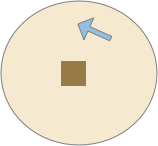

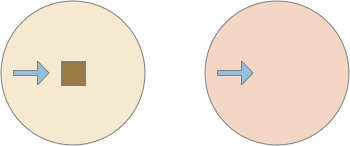

When seeking an odor, vertebrate swimming undulates left and right, naturally moving the nose perpendicular to the body motion. This lateral motion can help navigation if odor sampling can be coordinated with the movement, enabling a spatiotemporal gradient calculation along the path of the nose movement. This lateral sampling over time is called klinotaxis (“leaning navigation”) or weathervaning.

Essay 24 and essay 25 explored head-direction navigation as inspired by the fruit fly Drosophila fan-shaped body and ellipsoid body. The idea was to use head direction to translate egocentric movement into an allocentric memory of past samples, independent of the current body direction. In contrast, klinotaxis uses an egocentric system, where the lateral motion is relative to the current direction, not an independent, compass or map-like system.

Klinotaxis in Drosophila larva and C. elegans

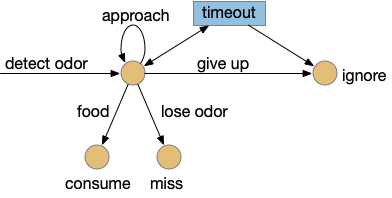

Klinotaxis has been largely studied in the fruit fly Drosophila larva and the roundworm C. elegans. Drosophila larva have a distinct “cast” movement, where they pause and wave their heads side to side, either a single time (1-cast) or multiple times (n-cast) [Zhao et al 2017]. Larva movements break down into five major types [Gomez-Marin and Louis 2014]:

- Forward

- Backward

- Stop

- Turn

- Cast

C. elegans has two major seek movements: pirouettes and weathervaning [Lockery 2011]. Pirouettes are a u-turn when the animal is moving away from the odor. Weathervaning is a side-to-side head movement that manages turning.

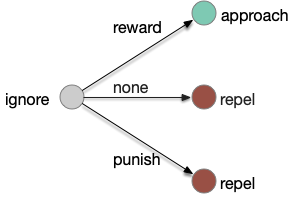

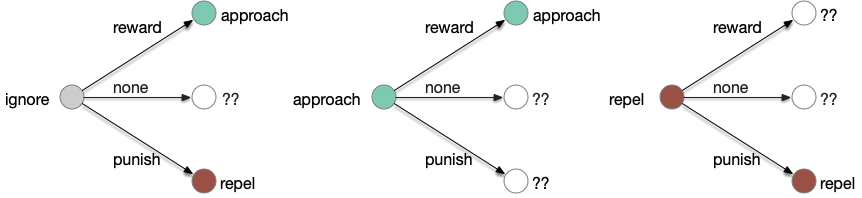

Both systems are temporal gradient systems, requiring measurements at different times and a memory of the older measurement [Chen X and Engert 2014]. Klinotaxis requires a basic form of memory [Karpenko et al 2020], but the comparison can be a simple ON or OFF result [Lockery 2011]. Pirouetts use a gradient parallel to body motion and reverse direction when the animal is moving away from the odor [Iino and Yoshida 2009]. Weathervaning uses a gradient perpendicular to body motion, measured with a lateral head movement [Lockery 2011].

This klinotaxis contrasts with a bilateral spatial navigation that compares two lateral sensors [Chen X and Engert 2014], such as bilateral eyes, ears, or nostrils. In Drosophila larva, odor turning is proportional to the lateral gradient more than the parallel gradient [Martinez 2014]. The odor navigation is not simply bilateral because disabling one side of O.sn (olfactory sensory neuron) only minimally impairs navigation [Gomez-Marin and Louis 2014].

As a slight digression, let’s return to the adult Drosophila navigation, because the structure can be a useful analogy for understanding vertebrate klinotaxis navigation, despite using a different allocentric system.

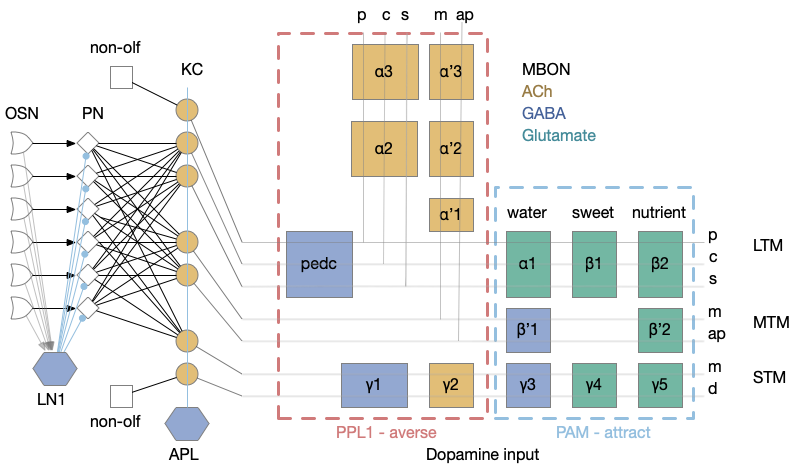

Adult Drosophila FSB

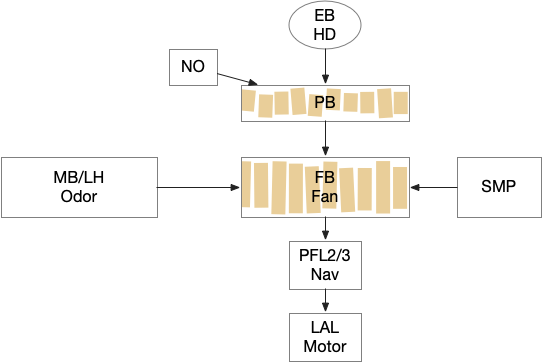

Below is a rough sketch of the Drosophila navigation circuit, focused on the fan-shaped body [Hulse et al 2021]. The ellipsoid body (EB) and protocerebral bridge (PB) calculate head direction and sort it into 18 columns. This head direction is allocentric, independent of the animal’s current direction, like a compass direction or a map. Input from odor areas like the mushroom body (MB) and lateral horn (LN) are organized into 9 rows. The fan-shaped body combines these 18 head direction columns and 9 sense data rows into a memory table.

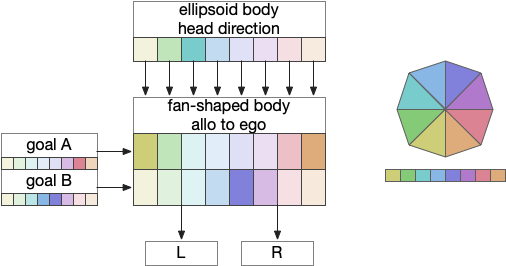

Motor navigation reads out from the fan-shaped-body table. These motor commands include left and right, but also include a separate u-turn command [Westeinde et al. 2022]. Although this allocentric navigation system differs from egocentric klinotaxis, its motor output includes both the left vs right from weathervaning and the u-turn from pirouette.

The previous essay 24 and essay 25 attempts followed this model. As the animal moves in space, the model saved the forward odor gradient according to the current head direction. By comparing stored values for other head directions, the animal would improve its heading toward the direction with the strongest odor.

The fan-shaped body then becomes a record of samples of all the older directions that the animal had measured. Output is then calculated for left (PFL3L), right (PFL3R), and u-turn (PFL2) signals. [Westeinde et al 2024]. The current head direction is represented as a sinusoidal neural pattern and combined with the stored values to produce an output.

This system was only partially successful for the essay. Although it was an improvement over no memory, because the animal was continually moving in space, the table was always obsolete. Even when the table memory times out to represent loss in accuracy as the animal moves, the rapid obsolescence made navigation difficult, particularly as the animal neared the target.

So, this essay simplifies the circuit and lowers the ambition. Instead of trying to record every direction and keeping perfect allocentric compass direction, the animal could simple save its left and right oscillation as it swims naturally.

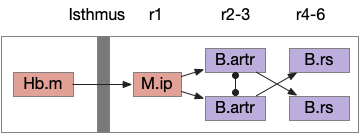

Vertebrate Hb.m and R.ip

The vertebrate Hb.m (medial habenula) to R.ip (interpeduncular nucleus) is used for phototaxis [Chen X and Engert 2014], Chemotaxis [Chen WY et al 2019] and thermotaxis [Palieri et al 2024]. In a clever experiment creating a virtual light circle, Chen and Engert shows that the zebrafish phototaxis is not simply comparing light between the eyes for a spatial gradient (tropotaxis) but is a temporally-based gradient (klinotaxis), relying on a short term memory of the previous light. This phototaxis uses the Hb.m to R.ip circuit [Chen X and Engert 2014].

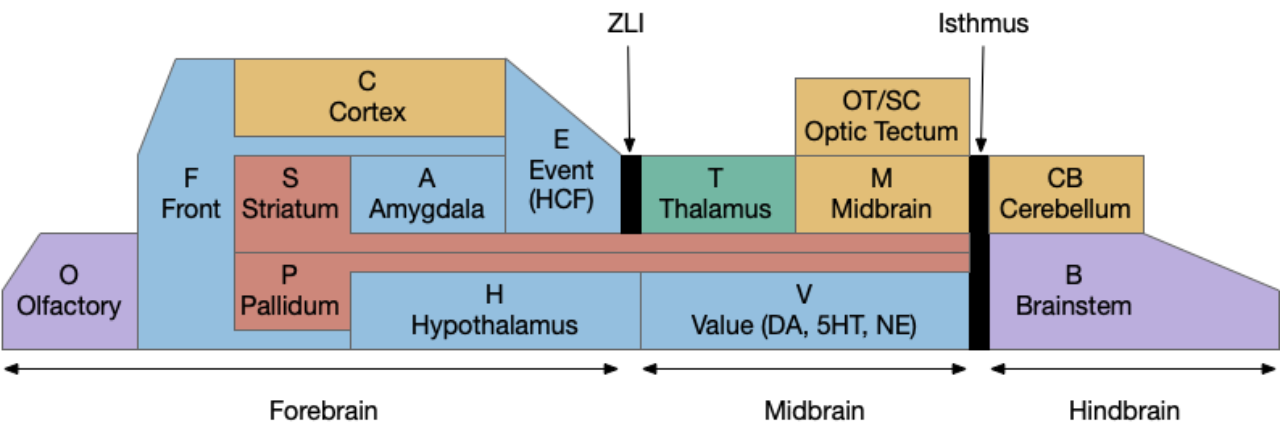

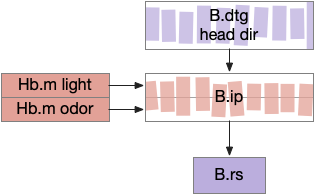

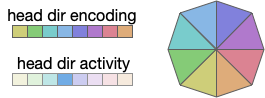

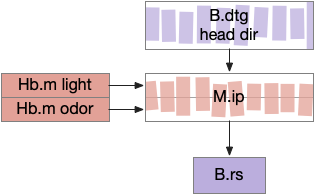

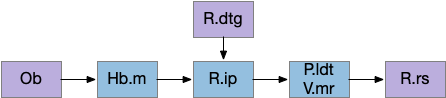

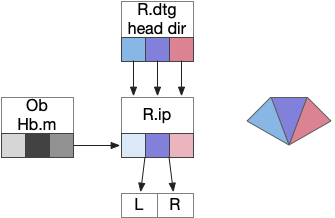

Head direction from R.dgt (dorsal tegmental nucleus) tiles R.ip vertically [Petrucco et al 2023], while olfactory and light input is organized horizontally [Chen WY et al 2019], [Zaupa et al 2021]. After combining the odor with the head direction and comparing with the stored values, it sends motor commands to R.rs (reticulospinal) using P.ldt (laterodorsal tegmental nucleus) and V.mr (median raphe). The vertebrate R.ip has 6 columns of head direction input from R.dtg, resembling the Drosophila fan-shaped body, but instead of 18 columns for the fan-shaped body, R.ip only has 6, three to a side [Petrucco et al 2023].

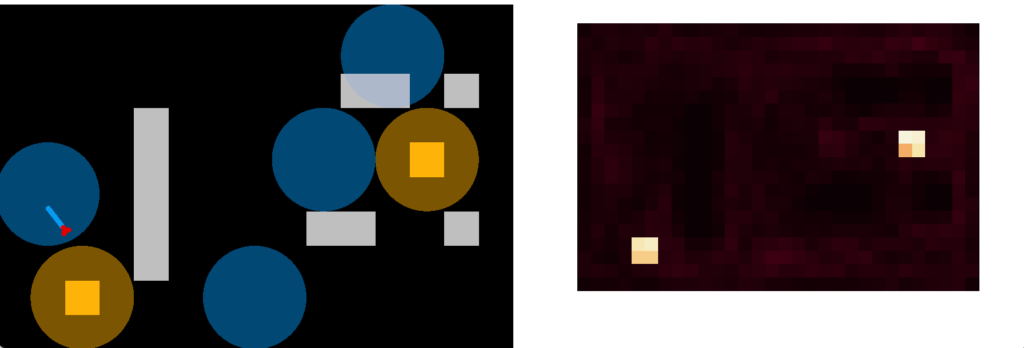

Essay 25 explored a model which used the Drosophila fan-shaped body allocentric navigation in R.ip with some limited but not overwhelming success. Instead, this essay will try a different interpretation, where R.ip is only storing side to side weathervaning of the head while swimming, instead of a full 360 degree table like Drosophila.

Vertebrate klinotaxis

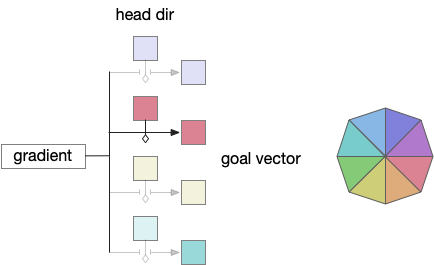

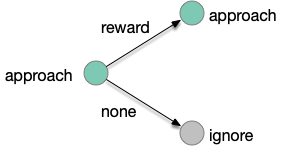

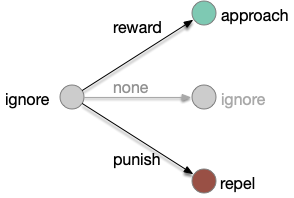

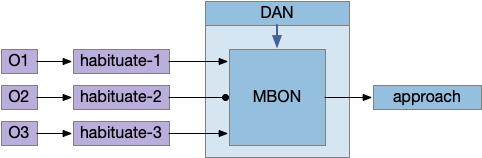

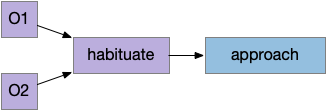

As a different approach, suppose the head direction to R.ip is not an allocentric map-making coordinator as in the adult Drosophila, but a simpler egocentric weathervaning or casting coordinator, storing only the lateral gradient from head direction changes from natural swimming, or possibly deliberate larger turns like casting to gather wider lateral gradient information.

Klinotaxis simplifies the need for precise head direction. Instead of the Drosophila 18 head direction columns calibrated to the outside world, we use only three, two lateral and one central, that only require motor efference copies of left and right muscle turns. Studies from the zebrafish R.ip suggest three columns to a side, which isn’t connected to the vestibular system [Petrucco et al 2023]. To me, this suggests to me that the head direction might not be an allocentric signal that requires precise direction, but a simple egocentric lateral measurement, which doesn’t need vestibular information.

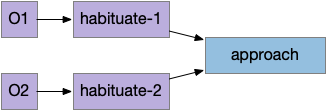

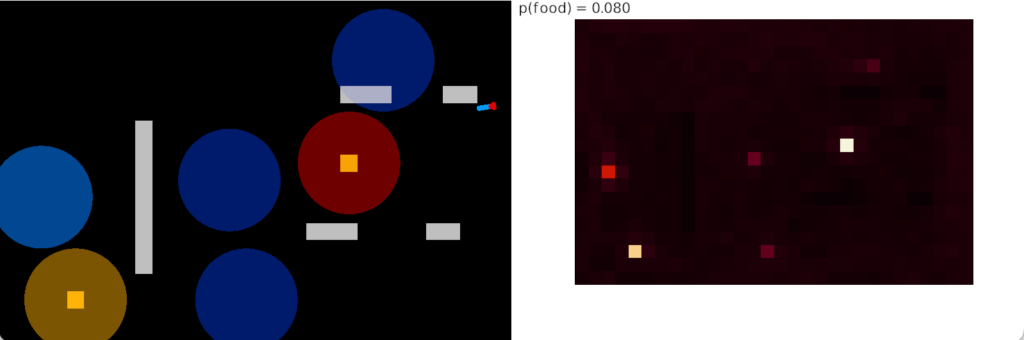

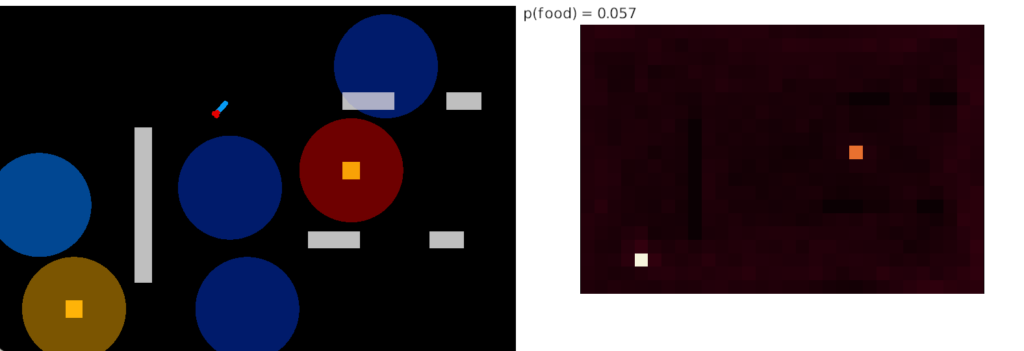

The above diagram illustrates the system. Olfactory samples arrive through Hb.mand head direction arrives from R.dtg. Like the Drosophila fan-shaped body, R.ip combines odor samples with lateral head movement into a simple memory table, and it reads out left and right motor commands. A similar system can save odor measurements parallel to body movement, using velocity instead of head direction, to trigger a u-turn when the animal is moving away from the odor.

Discussion

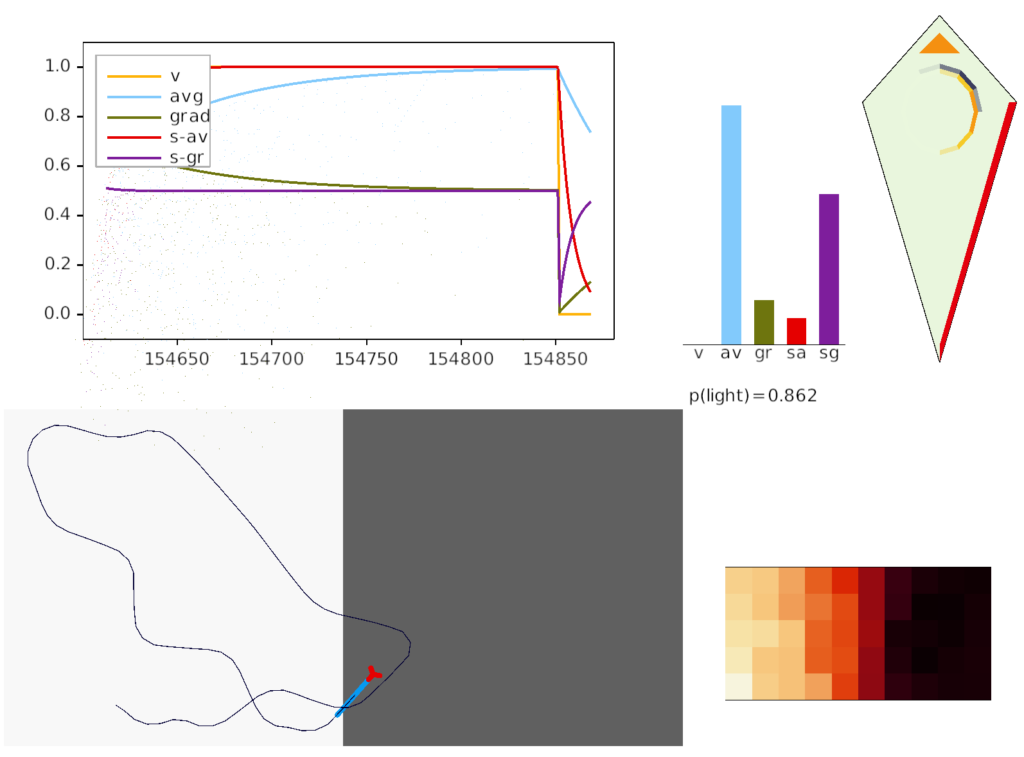

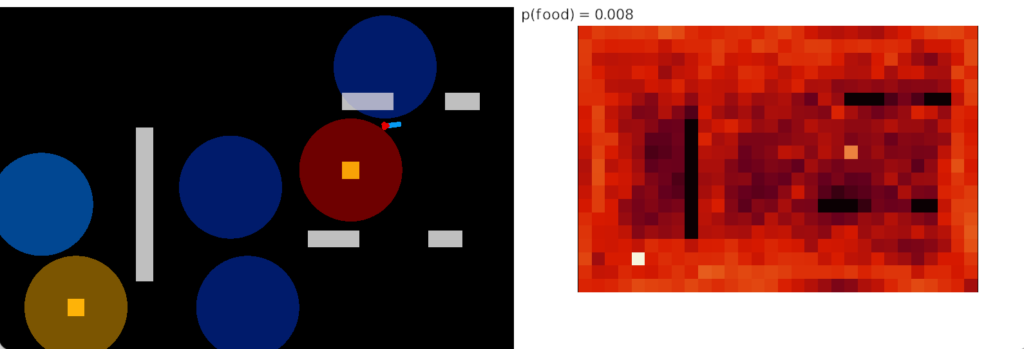

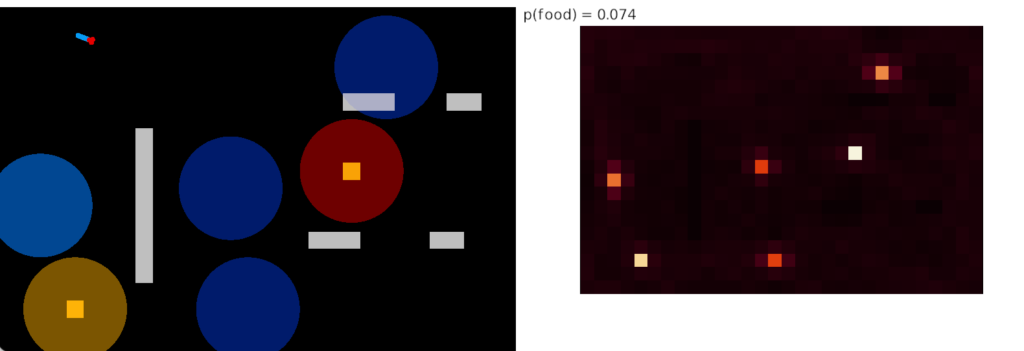

Compared to the parallel-only gradient, allocentric system of essay 25, this lateral navigation is far simpler and more effective. Even with only three bins compared to the 8 bins in essay 25, the lateral weathervaning turned out to be more effective and less brittle. If R.ip does implement a lateral klinotaxis system like this essay, it’s plausible that the 6 directions reported by [Westeinde et al 2024] are sufficient for accurate seek navigation. In contract, those 6 directions seem insufficient for an allocentric navigation compared to the Drosophila 18 directions.

Interestingly, the pirouette also highly effective, even without lateral klinotaxis. In the simulation, when the animal moved away from the odor source, it makes a u-turn. This system served to ratchet the animal closer and closer to the target. Even when most of the movement was random, the pirouette locks in any improvement. Pirouette itself is also simple, only requiring two averages: a short average and a long average, where a short average tracks the odor across a single swim cycle and a long average uses two swim cycles. When the short average has a stronger odor value than the long average, the animal is moving toward the odor.

In both cases, the simulation used a binary OFF for the motor command instead of attempting finer precision from the gradient. This simple OFF strategy was sufficient for the simulation. A C. elegans study suggested that ON-OFF coding was energy efficient, and the worm rarely orients perfectly to the gradient [Lockery 2011].

References

Chen WY, Peng XL, Deng QS, Chen MJ, Du JL, Zhang BB. Role of Olfactorily Responsive Neurons in the Right Dorsal Habenula-Ventral Interpeduncular Nucleus Pathway in Food-Seeking Behaviors of Larval Zebrafish. Neuroscience. 2019 Apr 15;404:259-267.

Chen X, Engert F. Navigational strategies underlying phototaxis in larval zebrafish. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014 Mar 25;8:39.

Gomez-Marin A., Louis M. (2014). Multilevel control of run orientation in Drosophila larval chemotaxis. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 8:38 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00038.

Hulse, B. K., Haberkern, H., Franconville, R., Turner-Evans, D., Takemura, S. Y., Wolff, T., … & Jayaraman, V. (2021). A connectome of the Drosophila central complex reveals network motifs suitable for flexible navigation and context-dependent action selection. Elife, 10.

Iino Y, Yoshida K. Parallel use of two behavioral mechanisms for chemotaxis in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2009 Apr 29;29(17):5370-80.

Karpenko S, Wolf S, Lafaye J, Le Goc G, Panier T, Bormuth V, Candelier R, Debrégeas G. From behavior to circuit modeling of light-seeking navigation in zebrafish larvae. Elife. 2020 Jan 2;9:e52882.

Lockery SR. The computational worm: spatial orientation and its neuronal basis in C. elegans. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2011 Oct;21(5):782-90.

Martinez D. Klinotaxis as a basic form of navigation. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014 Aug 14;8:275.

Palieri V, Paoli E, Wu YK, Haesemeyer M, Grunwald Kadow IC, Portugues R. The preoptic area and dorsal habenula jointly support homeostatic navigation in larval zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2024 Feb 5;34(3):489-504.e7.

Petrucco L, Lavian H, Wu YK, Svara F, Štih V, Portugues R. Neural dynamics and architecture of the heading direction circuit in zebrafish. Nat Neurosci. 2023 May;26(5):765-773.

Westeinde EA, Kellogg E, Dawson PM, Lu J, Hamburg L, Midler B, Druckmann S, Wilson RI. Transforming a head direction signal into a goal-oriented steering command. Nature. 2024 Feb;626(8000):819-826.

Zaupa M, Naini SMA, Younes MA, Bullier E, Duboué ER, Le Corronc H, Soula H, Wolf S, Candelier R, Legendre P, Halpern ME, Mangin JM, Hong E. Trans-inhibition of axon terminals underlies competition in the habenulo-interpeduncular pathway. Curr Biol. 2021 Nov 8;31(21):4762-4772.e5.

Zhao W, Gong C, Ouyang Z, Wang P, Wang J, Zhou P, Zheng N, Gong Z. Turns with multiple and single head cast mediate Drosophila larval light avoidance. PLoS One. 2017 Jul 11;12(7):e0181193.