In the fruit fly Drosophila, the mushroom body is an olfactory associative learning hub for insects, similar to the amygdala (or hippocampus or piriform, O.pir) of vertebrates, learning which odors to approach and which to avoid. Although the mushroom body (MB) is primarily focused on olfactory senses, it also receives temperature, visual and some other senses. The genetic markers for MB embryonic development in insects match the markers for cortical pyramidal neurons and other learning neurons like the cerebellum granule cells.

While most studies seem to focus on the mushroom body as an associative learning structure, others like [Farris 2011] compare it to the cerebellum for action timing and adaptive filtering.

Essay 15 will likely expand the essay 14 slug that avoided obstacles, adding odor tracking. The mushroom body should show how to improve the slug behavior without adding too much complexity.

- 15: Food seeking, perseveration, and habituation

- Essay 14: navigation: obstacles and food

- Essay 16: learning to ignore (caching)

Mushroom body architecture

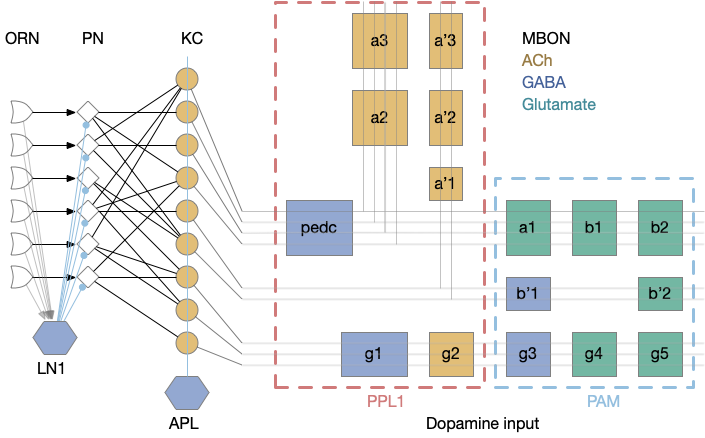

The mushroom body is a highly structured system, comprised of Kenyon cells (KC), mushroom body output neurons (MBONs), and dopamine (DAN) and optamine (OAN) neurons (collectively MBIN – mushroom body input neurons). The outputs are organized into exactly output compartments, each with only one or two output neurons (MBONs) [Aso et al. 2014].

The 50 primary olfactory neurons (ORN) and 50 projection neurons (PN) project to 2,000 KC neurons. Each KC neuron connects to 6-8 PNs with claw-like dendrites. The 2,000 KC neurons then converge to 34 MBONs. In vertebrates, divergence-convergence pattern occurs in the cerebellum with granule cells to Purkinje cells, in the hippocampus with dentate gyrus to CA3, in the striatum with MSN (medium spiny neurons) to S.nr/S.nc (substantia nigra), and in cortical areas with large granular areas.

Habituation (ORN, PN, LN1)

Olfactory habituation is handled by the LN1 circuit from the olfactory receptor neuron (ORN) to projection neuron (PN) connection. The fly will ignore an odor after 30 minutes, and the odor remains ignored for 30 to 60 minutes. Since the LN1 GABA inhibition neuron implements the habituation, suppressing LN1 can reverse habituation nearly instantly.

Habituation is odor-specific because it’s synapsed based, but a single neuron inhibits multiple odors. (There are multiple LN1 inhibitors, but they’re not odor-specific and inhibit multiple odors.) Habituation is odor-specific because it inhibits on a per-synapse system. LN1 doesn’t inhibit the PN, but inhibits the synapse from an ORN to the target PN. So, only figuring PNs trigger habituation, despite relying on a shared inhibitory neuron. [Shen 2020].

Sparse KC firing (KC, APL)

The 50 projection neurons (PNs) diverge into 2,000 Kenyon cells(KC). Each KC has 6-8 claw-like dendrites to 6-8 PNs. Each fly has a random connection between the PNs and its KCs. The KCs that fire for an odor form a “tag,” which is essentially a hash of the odor inputs.

About 5% of the KCs fire for any odor, which is strictly enforced by the APL circuit. APL is a single inhibitory GABA neuron per side that reciprocally connects with all 2,000 KCs. The APL inhibition threshold ensures only the strongest 5% of KCs will fire.

A computer algorithm by [Dasgupta et al. 2017] uses this KC tag for a “fly hash” algorithm, which computes a hash using a random, sparse connection for locality-sensitive hashing (LSH). LSH retains information from the origin data to retain distance between hashes as reflective as distance between odors. Interestingly, they use the fly hash with visual input, treating pixels as equivalent to odors. Despite the significant differences between unique odors and arbitrary pixels, the results for the fly hash are better than other similar LSH systems.

Dopamine and compartments (MBON, DAN)

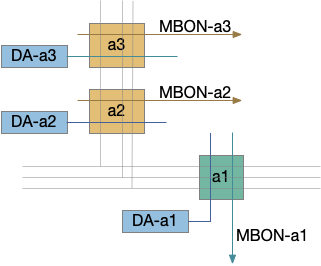

The output compartments for the mushroom body are broadly organized into attractive and repellant groups with seven repelling compartments and nine attracting compartments. Three of the compartments (g1-g3) feed forward into other compartments.

Each compartment is fed by one or two dopamine neuron types (DAN), for a total of 20 DAN types for 16 MBON compartments. The repellant section (PPL1) is even more restricted with exactly one dopamine neuron per compartment. The attractive section (PAM) has a bound 20 DAN cells per compartment.

In a study of larval Drosophila [Eichler et al. 2020] studied the entire connectome of the mushroom body and found highly specific reciprocal MBON connections, inhibitory, directly excitatory and axon excitatory.

An [Eschbach et al. 2020] study looked at dopamine (DAN) connective. Each DAN type has distinct inputs from raw value stimuli (unconditioned stimuli – US), and also internal state, and feed back from the mushroom body. So, while the DANs do convey unconditioned stimuli for learning, they’re not a simplistic reward and punishment signal.

Essay 15 simulation direction

Essay 15 will likely continue the slug-like animal from essay 14, and add odor approaching. Because I think the slug will need habituation immediately, I’ll probably explore habituation first.

The essay will probably next explore a single KC to a single MBON, simulating a single odor.

I’m tempted to explore multiple MBON compartments before exploring multiple KCs. Partially for general contrariness: pushing against the simple reward/punishment model to see if it goes anywhere, or if multiple dopamine sources needlessly complicated learning.

And, actually, since I want to push against learning as a solution for everything, to see how much of the mushroom body function can work without any learning at all, treating habituation as short term memory, not learning.

References

Aso Y, Hattori D, Yu Y, Johnston RM, Iyer NA, Ngo TT, Dionne H, Abbott LF, Axel R, Tanimoto H, Rubin GM. “The neuronal architecture of the mushroom body provides a logic for associative learning.” Elife. 2014 Dec 23;3:e04577. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04577. PMID: 25535793; PMCID: PMC4273437.

Dasgupta S, Stevens CF, Navlakha S. “A neural algorithm for a fundamental computing problem.” Science. 2017 Nov 10;358(6364):793-796. doi: 10.1126/science.aam9868. PMID: 29123069.

Eichler, Katharina, et al. “The complete connectome of a learning and memory centre in an insect brain.” Nature 548.7666 (2017): 175-182.

Eschbach, Claire, et al. “Recurrent architecture for adaptive regulation of learning in the insect brain.” Nature Neuroscience 23.4 (2020): 544-555.

Farris, Sarah M. “Are mushroom bodies cerebellum-like structures?.” Arthropod structure & development 40.4 (2011): 368-379.

Shen Y, Dasgupta S, Navlakha S. “Habituation as a neural algorithm for online odor discrimination.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 Jun 2;117(22):12402-12410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1915252117. Epub 2020 May 19. PMID: 32430320; PMCID: PMC7275754.