Essay 15 is adding food-seeking to the simulated slug. Before the change in essay 14, the slug didn’t seek from a distance, but it does slow when it’s above food to improve feeding efficiency. The slug doesn’t have food-approach behavior, but it does have consummatory behavior. Because the slug doesn’t seek food, it only finds food when it randomly crosses a tile. Most of its movement is random, except for avoiding obstacle.

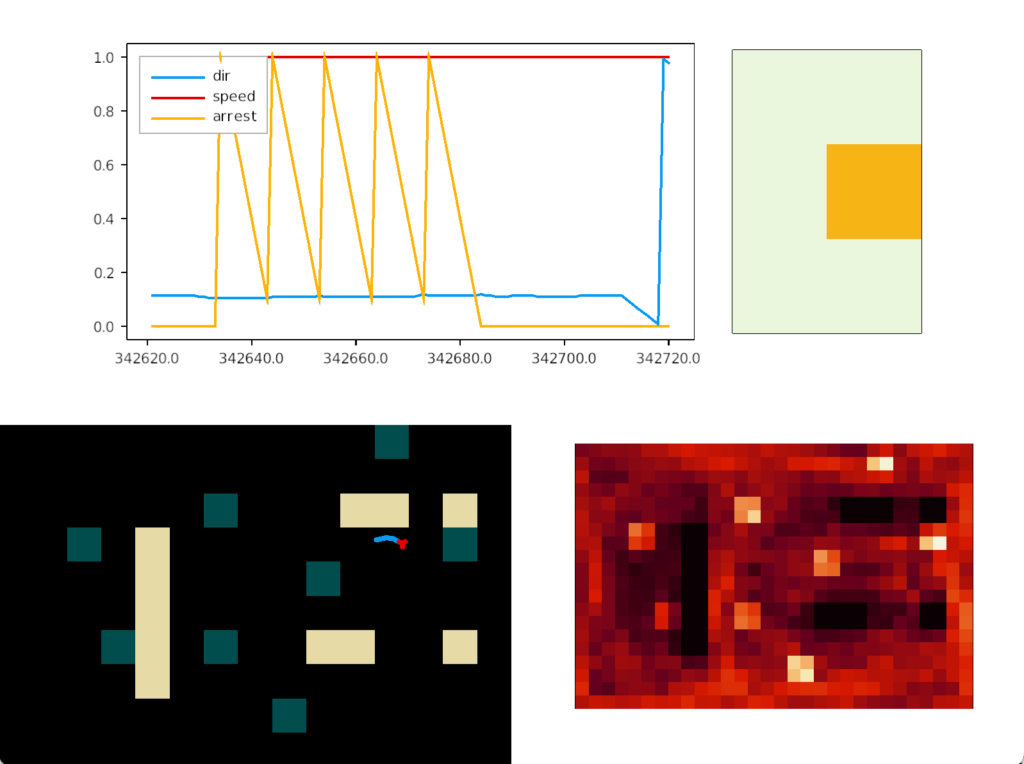

In the screenshot above, the slug is moving forward with no food senses and no food approach. Its turns are for obstacle avoidance. The food squares have higher visitation because of the slower movement over food. Notice that all areas are visited, although there is a statistical variation because of the obstacle.

Although the world is tiled for simulation simplicity, the slug’s direction, location, and movement is floating-point based. The simulation isn’t an integer world. This continuous model means that timing and turn radius matters.

The turning radius affects behavior in combination with timing, like the movement-persistence circuit in essay 14. The tuning affects the heat map. Some turning choices result in the animal spending more time turning in corners when the dopamine runs out. This turn-radius dependence occurs in animals as well. The larva zebrafish has 13 stereotyped basic movements, and its turns have different stereotyped angles depending on the activity.

Food approach

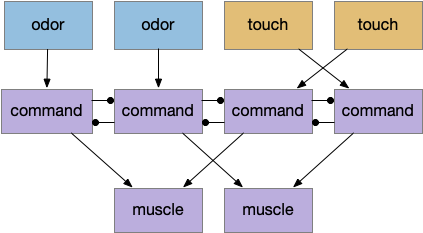

Food seeking adds complexity to the neural circuit, but it’s still uses a Braitenberg vehicle architecture. (See the discussion on odor tracking for avoided complexity.) Odor sensors stimulate muscles in uncrossed connections to approach the odor. Touch sensors use crossed connections to avoid obstacles. For simultaneous odor and touch, an additional command neuron layer resolves the conflict to favor touch.

The command neurons correspond to vertebrate reticulospinal neurons (B.rs) in the hindbrain. Interestingly, the zebrafish circuit does seem to have direct connections from the touch sensors to B.rs neurons, exactly as pictured. In contrast, the path from odor receptors to B.rs neurons is a longer, more complicated path.

For the slug’s evolutionary parallel, the odor’s attractively is hardcoded, as if evolution has selected an odor that leads to food. Even single-celled animals follow attractive chemicals and avoid repelling chemicals, and in mammals some odors are hardcoded as attractive or repelling. For now, no learning is occurring.

Perseveration (tunnel vision)

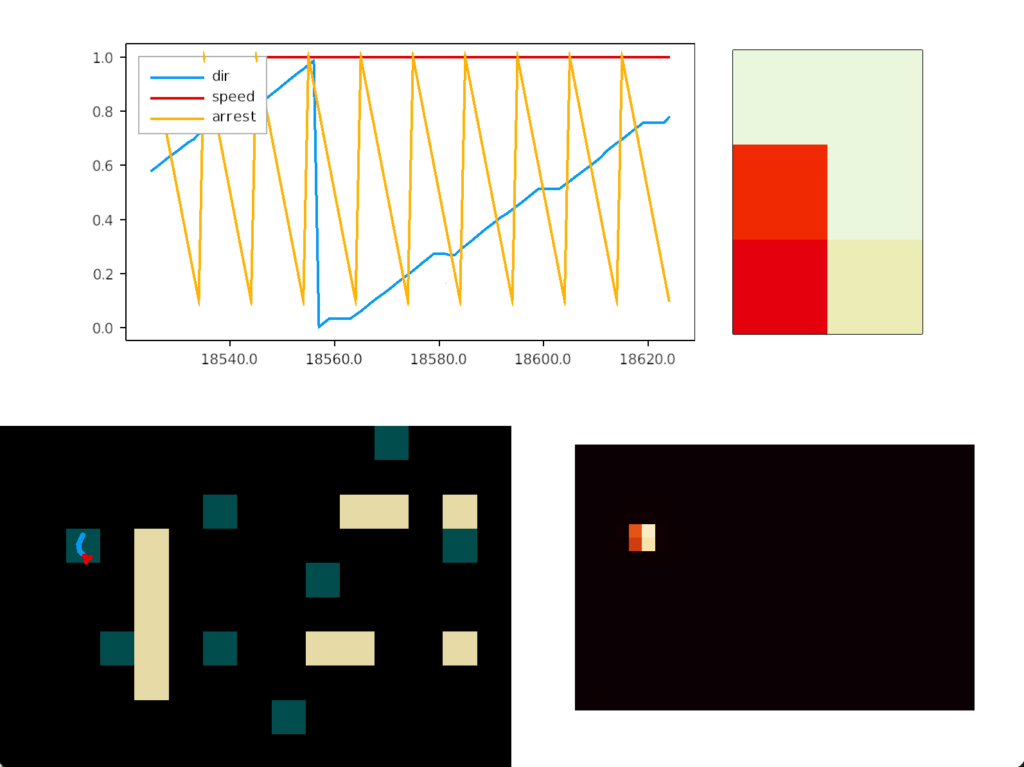

Unfortunately, this simple food circuit has an immediate, possibly fatal, problem. Once the slug detects an odor, it’s stuck moving toward it because our circuit can’t break the attraction. Although the slug never stops, it orbits the food scent, always turning toward it. The hoped-for improvement of following an odor to find food is a disaster.

In psychology, this inability to switch away is called perseveration, which is similar to tunnel vision but more pathological. Once a goal is started, the person can’t break away. In reinforcement learning terminology, the inability to switch is like an animal stuck on exploiting and incapable of breaking away to explore.

In the screenshot, the heat map shows the slug stuck on a single food tile. The graph shows the slug turning counter-clockwise, slowed down (sporadically arrested) over the food.

To solve the problem, one option is to re-enabled satiation for the simulation, as was added in essay 14, but satiation only solves the problem if the tile has enough food to satiate the animal. Unfortunately, the tile might have a lingering odor but no food, or possibly an evolutionary food odor that’s unreliable, only signaling food 25% of the time. Instead, we’ll introduce habituation: the slug will become bored of the odor and start ignoring it for a time.

In the fruit fly the timescale for habituation is about 20 minutes to build up and 20-40 minutes to recover. The exact timing is likely adjustable because of the huge variability in biochemical receptors. So, 20 minutes probably isn’t a hard constant across different animals or circuits for habituation, but more of a range between a few minutes or an hour or so.

Because the minutes to hour timescale for habituation is much wider than the 5ms to 2s range for neurotransmitters, the biochemical implementation is very different. Habituation seems to occur by adding receptors to increase receptor and/or adding more neurotransmitter generators to produce a bigger signal.

Fruit fly odor habituation

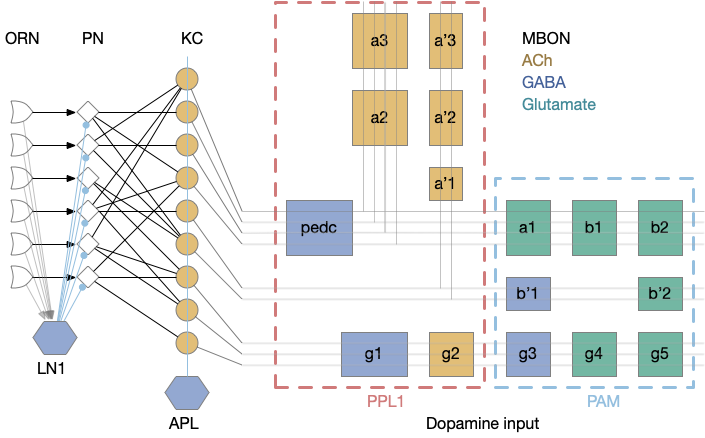

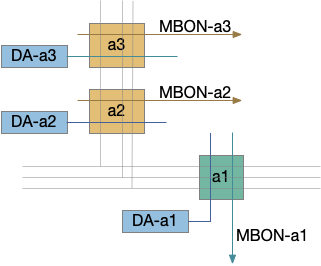

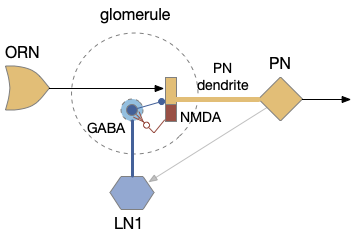

[Das 2011] studies the biochemical circuit for fruit fly odor habituation. The following diagram tries to capture the essence of the circuit. The main, unhabituated connection is from the olfactory sensory neuron (ORN) to the projection neuron (PN), which projects to the mushroom body. The main fast neurotransmitter for insects is acetylcholine (ACh), represented by beige.

The key player in the circuit is the NMDA receptor on the PN neuron’s dendrite, which works with the inhibitory LN1 GABA neuron to increase inhibition over time to habituate the odor.

The LN1 neuron drives habituation. Its GABA neurotransmitter release inhibits PN, which reduces the olfactory signal. Because LN1 itself can be inhibited, this circuit allows for a quick reversal of habituation. Habituation adds to simple inhibition by increasing the synapse strength (weight) over time when its used and decreasing the weight when its idle.

An NMDA receptor needs both a chemical stimulus (glutamate and glycine) and a voltage stimulus (post-synaptic activation, PN in this case). When activated, it triggers a long biochemical chain with many genetic variations to change synapse weight. In this case, it triggers a retrograde neurotransmitter (such as nitrous oxide, NO) to the pre-synaptic LN1 axon, directing it to add new GABA release vesicles. Because adding new vesicles takes time (20 minutes) and removing the vesicles also takes time (20-40 minutes), habituation adds longer, useful behavior that will help solve the odor perseveration problem.

Slug with habituation

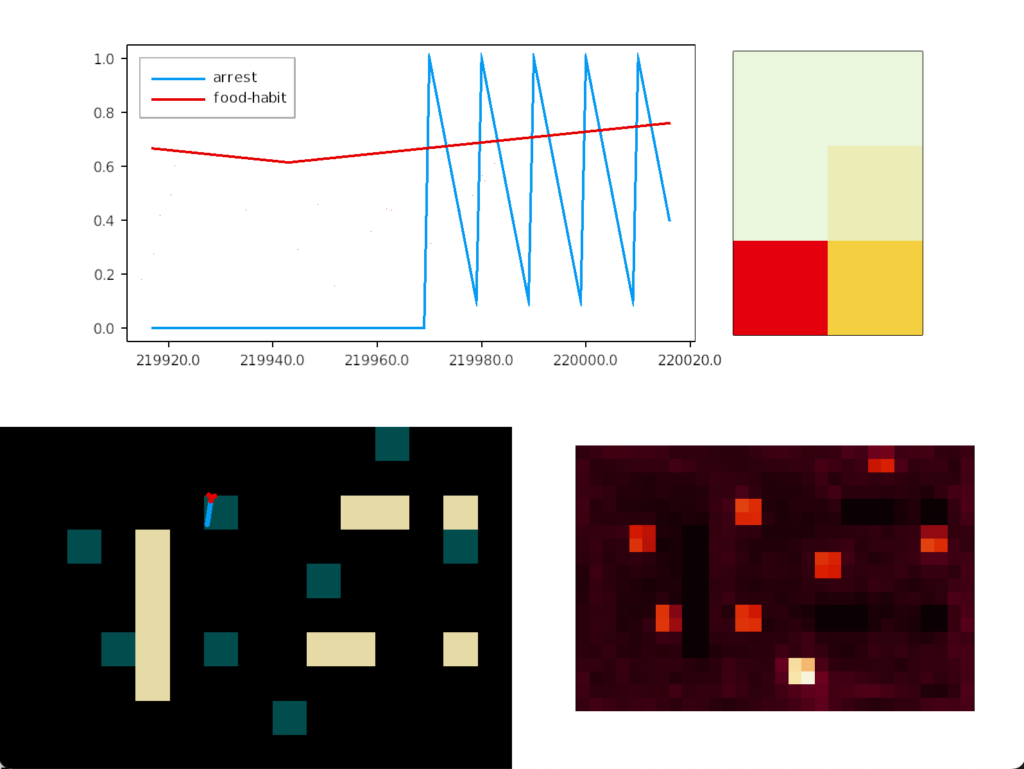

The next slug simulation adds trivial habituation following the example of the fruit fly. The simulation adds a value when the slug senses an odor and decrements the value when the slug doesn’t detect an odor. When habituation crosses a threshold, the odor sensor is cut off from the command neurons. The behavior and heat map look like the following:

As the heat map shows, habituation does solve the fatal problem of perseveration for food approach. The slug visits all the food nodes without having any explicit directive to visit multiple nodes. Adding a simple habituation circuit, creates behavior that looks like an explore vs exploit pattern without the simulation being designed around reinforcement learning. Explore vs exploit emerges naturally from the problem itself.

In the screenshot, the bright tile has no intrinsic meaning. Because habituation increases near any food tile, it can only decay when away from food. That bright tile is near a big gap that lets habituation to drop and recharge.

The code looks like the following:

impl Habituation {

fn update_habituation(&mut self, is_food_sensor: bool) {

if is_food {

self.food = (self.food + Self::INC).min(1.);

} else {

self.food = (self.food - Self::DEC).max(0.);

}

}

fn is_active(&self) -> bool {

self.food < Self::THRESHOLD

}

}Discussion

The essays aren’t designed as solutions; they’re designed as thought experiments. So, their main value is generally the unexpected implementation details or issues that come up in the simulation. For example, how habituation thresholds and timing affect food approach. The bright tile in the last heat map occurs because that food source is isolated from other food sources.

If the slug passes near food sources, the odor will continually recharge habituation and it won’t decay enough to re-enable chemotaxis. The slug needs to be away from food for some time for odor tracking to re-enable. In theory, this behavior could be a problem for an animal. Suppose the odor range is very large and the animal is very slow, like a slug. If simple habituation occurs, the slug might habituate to the odor before it reaches the food, making it give up too soon.

As a possible solution, the LN1 inhibitory neuron that implements habituation could itself be disabled, although that beings back the issue of the animal getting stuck. But perhaps it would instead be diminished instead of being cut off, giving the animal persistence without devolving into perseveration.

Odor vs actual food

Another potential issue is the detection of food itself as opposed to just its odor. If the food tile has food, the animal should have more patience than if the tile is empty with just the food odor. That scenario might explain why other habituation circuits include serotonin or dopamine as modulators. If food is actually present, there should be less habituation.

The issue of precise values raises calibration as an issue, because evolution likely can’t precisely calibrate cutoff values or calibrate one neuron to another. Some of the habituation and related synapse adjustment may simply be calibration, adjusting neuron amplification to the system. In a sense, that calibration would be learning but perhaps atypical learning.

References

Das, Sudeshna, et al. “Plasticity of local GABAergic interneurons drives olfactory habituation.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108.36 (2011): E646-E654.

Shen Y, Dasgupta S, Navlakha S. Habituation as a neural algorithm for online odor discrimination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 Jun 2;117(22):12402-12410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1915252117. Epub 2020 May 19. PMID: 32430320; PMCID: PMC7275754.