The first two parts of this essay were a general overview of the necessity of sleep and some of the properties. Here I’m going over some of the brainstem circuits that control sleep.

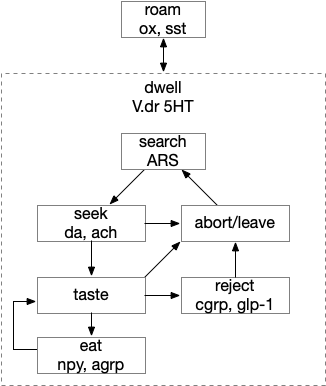

Wake ignition

Waking requires intrinsic motivation because sleeping places the animal away from distraction, to an extreme in hibernation. A short nap, as is more typical in the waking period, needs to end without needing external stimulus or an internal one like hunger. What’s needed is an internal ignition source to drive wake and motivation.

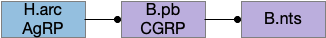

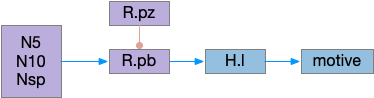

In rodents, if the area around R.pb (parabrachial nucleus in r1) is lesioned, the animal remains in a coma [Fuller et al 2011]. For humans, a study of coma showed a pattern of the same area as consistently being destroyed [Grady et al 2022]. However, the exact cells aren’t known, and other studies that lesion R.pb for conditioned taste studies don’t produce coma. Still, this site seems a likely ignition area.

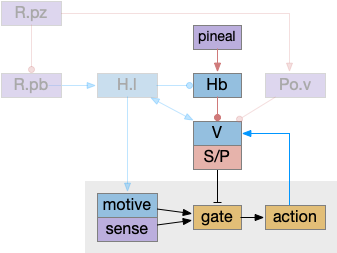

The above diagram shows a possible wake ignition circuit. The area around R.pb is the main wake ignition node. R.pb produces wake by stimulating motivational areas like H.l (and others).

It’s not known if the R.pb area is self-igniting or if astrocytes in the area are critical, or if it uses peripheral wake signals such as N5 (trigeminal nerve), N10 (vagus nerve), or N.sp (spinal cord or other periphery) [Grady et al 2022]. In the fruit fly Drosophila specialized peripheral leg neurons can promote daytime sleep [Jones et al 2023]. These specialized neurons are distinct from sensor or motor neurons. In addition peripheral neurons from Drosophila PPM area are wake promoting [Satterfield et al 2022]. So, it seems plausible that peripheral nerves such as N5, N10, or N.sp could have similar wake-producing neurons, although this is entirely speculative.

If R.pb is a wake-ignition system, then sleep needs to suppress it, whether by internal clock regulation, or external suppression. In the hindbrain, R.pz (parafacial zone near N7 and r5 / r6) suppresses R.pb to create sleep [Anaclet et al 2014]. Disabling R.pz decreases NREM sleep by 30% [Erikson et al 2019].

Hindbrain (rhombomere) sleep

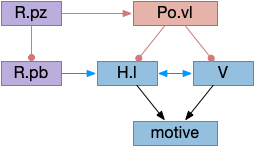

R.rs (reticulospinal) neurons in the caudal hindbrain (medulla, r6-r8) have both wake and sleep effects. Because R.rs are motor control neurons, they need to suppress sleep while they’re active, but the same area also contains sleep promoting areas. So, when experimenters stimulate the area, the animal remains awake, but immediately following the end of stimulation the animal sleeps, because the sleep-inhibition is removed. [Teng et al 2022]. These R.rs neurons (ventrolateral medulla) send collaterals to Po.vl (ventrolateral preoptic area), which is a forebrain sleep / wake area.

Midbrain sleep

A specific nucleus near N3 (oculomotor nerve) and associated motor areas (Edinger-Westphal) is a sleep promoting area. Stimulating it increases NREM [Zhang et al 2019]. (I’m just noting this for reference. I don’t understand how this area connects with other sleep areas.)

Ventral preoptic area

Although wake-maintaining areas are widely distributed, and much of sleep-circuitry is postponing sleep for ongoing actions, sleep-promoting area are more rare. One sleep-promoting area is Po.vl (ventrolateral preoptic area) and Po.mn (median preoptic area), which are adjacent area. Po.vl is inhibitory GABA and inhibits neurotransmitter wake areas like V.lc (locus coeruleous – norepinephrine), Vta (dopamine), V.dr (serotonin), M.pag.v (which is V.dr but refers to a dopamine area), and Ppt (pedunculopontine nucleus – acetylcholine) and P.ldt (laterodorsal tegmental nucleus – also acetylcholine).

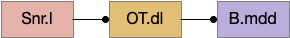

In the diagram above, Po.vl promotes sleep by inhibiting wake-promoting areas, here represented by H.l and V, where V includes the neurotransmitter wake areas. This Po.vl function is one pole of the flip-flop analogy [Saper et al 2001], driving sleep transitions faster and supporting continuous sleep, avoiding fragmentation.

Lateral Hypothalamus

H.l is a sleep wake hub [Gazea 2021] with both wake-promoting peptide orexin, and GABA neurons promoting wake. The orexin peptide is wake-related, because if it’s missing, people and animals develop narcolepsy and cataplexy. H.l orexin neurons project to other wake-promoting areas like V.lc, Ppt, V.dr, Vta, and is believed to sustain wakefulness.

Stimulating orexin neurons does produce wake after sleep, but only after 10-20 seconds, so these aren’t directly wake producing, but more wake facilitating. In contrast, V.lc norepinephrine neurons produce wake in 2 seconds [Yamaguchi et al 2018].

In addition, a study suggested that human orexin is low at dawn, a time when people are active and twos to peak at dusk [Mogavero et al 2023]. So orexin’s role is something more complicated than simply a wake-promoting peptide. (Note: this study seemed somewhat unreliable. I’d like to see a more detailed orexin over time study for rodents, where measurements can be more precise).

Other sleep and wake neurons exist in H.l without the orexin [Heiss et al 2018]. For example, some Vta GABA neurons that express SST (somatostatin) store sleep requirements for up to 5 hours, and signal the extra sleep need to H.l [Yu et al 2019].

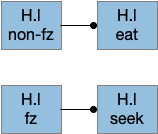

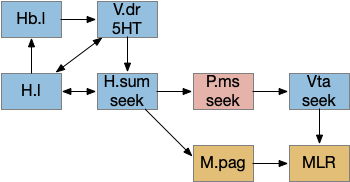

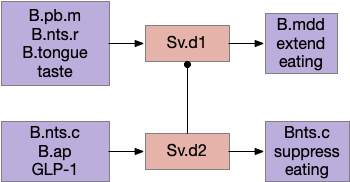

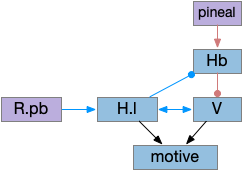

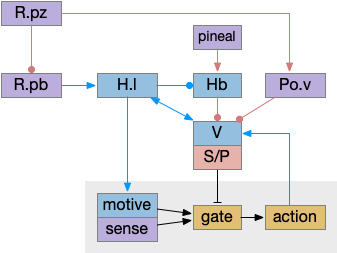

The above diagram shows two complementary roles for H.l. First, H.l can suppress Hb.l circadian sleep-promoting path with H.l orexin projections to Hb that inhibit anaesthesia [Zhou et al 2023] and promote aggressive arousal [Flanigan et al 2020].

The positive feedback loop from H.l to Hb (habenula) to V and back to H.l sustains wake. The gain for positive feedback could vary in circadian cycles. A high gain in the morning could produce full wake even with little activity. A low gain at night would make it harder to sustain wake.

Misc notes: Sleep preparation is a distinct, complicated pre-sleep behavior. One trigger seems to be from F.pl (pre limbic frontal cortex) SST neurons to H.l [Tossell et al 2023]. Astrocytes also seem to be involved with H.l wake, are active when waking and promoting wakefulness [Cai et al 2022]. H.pv is also sleep promoting and if it’s knocked out, significant daytime sleep increases, particularly in the morning [Chen et al 2021]. In contrast, the posterior hypothalamus has astrocytes that increase sleep at night [Pelluru et al 2016].

Vta sleep/wake glutamate and GABA

For the moment, let’s ignore Vta (ventral tegmental area) dopamine. Vta includes glutamate and GABA neurons that derive from r1 (hindbrain rhombomere 1) [Lahti et al 2016] that enhance wake with glutamate [Yu et al 2019] and enhance sleep with GABA [Chowdury et al 2019]. The tail of Vta, RMTg (rostromedial tegmental are in r2 / r3) is essential for NREM sleep [Yang et al 2018].

Vta glutamate, GABA, and DA all control sleep using H.l and S.msh (medial shell of the ventral stratum aka nucleus accumbens). As noted above, H.l is a coordinator of sleep and wake with not only orexin but also GABA and glutamate. Inhibiting Vta GABA bypasses sleep homeostasis, producing a mania state during circadian wake times [Yu et al 2021], [Yu et al 2022].

Vta glutamate stimulation promotes continuous wake independent of DA [Yu et al 2019], via projections to H.l, S.sh, and P.v (ventral pallidum), particularly the NOS1 cells.

Vta.g (GABA neurons of Vta) stimulation encourages NREM sleep. If Vta.g are inhibited, the animal remains 100% awake for hours, during the normal wake period, not the normal sleep period [Yu et al 2022]. The Hb.l projection to Vta.g is required for the anesthetic propofol to work [Gelegen et al 2018].

Interestingly, a specific SST (somatostatin) subset of Vta GABA retains a future sleep requirement from social defeat, where social defeat produces extra sleep. When the rodent loses a conflict, these Vta SST neurons have elevated calcium for up to five hours, and then the animal sleeps, these neurons fire to H.l, extending sleep duration [Yu et al 2019]. Speculating here, this multi-hour memory suggests a possible astrocyte involvement.

Returning the dopamine. Vta dopamine produces wake, while Vta dopamine inhibition produces sleep with nesting behavior [Eban-Rothschild et al 2016], as opposed to immediate collapse like narcolepsy. Low dopamine in a behaviorist experiment produces long decays, difficulty in locomotion and sleepiness [Nicola 2007]. However, other studies argue that dopamine itself is not wake promoting [Takata et al 2018].

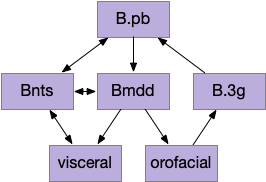

Habenula

As mentioned in a previous post, Hb (habenula) is a sleep-promoting area as a motor-inhibiting area driven by the pineal gland and extending melatonin’s role [Hikosaka 2012]. This sleep promoting area is in a positive feedback loop with the wake-promoting neurotransmitters and peptides.

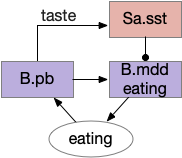

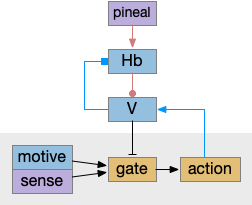

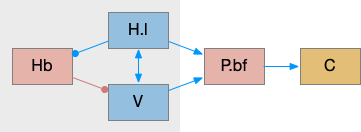

This above diagram is a different perspective on the prior H.l diagram, where I’ve merged H.l into V and made the motor and motivation suppression explicit. Here the wake-promoting neurotransmitters gate motivation and motor, extending the role of melatonin, which suppresses action.

Active actions promote wake and suppress sleep, like the R.rs wake efferent copies [Teng et al 2022], by stimulating the value neurons. In turn, the value neurons suppress the habenula such as Vta to Hb.l [Webster et al 2021] and serotonin inhibiting Hb.l [Tchenio 2016], H.l orexin and GABA also inhibit Hb.l [Flanigan 2020], [Gazea 2021]. As mentioned above, these positive feedback loops sustain wake despite sleep pressure.

Summary circuit

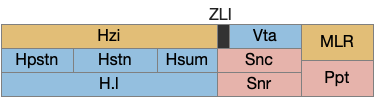

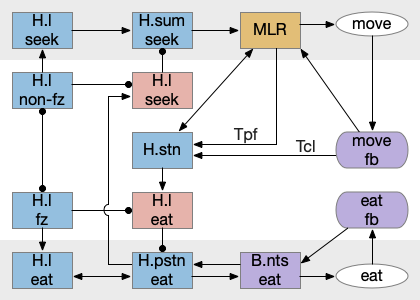

Putting these components of the sleep/wake circuit together produces something like the following, where I’ve emphasized the habenula to show how that subsystem fit into the whole circuit.

As before, the circadian sleep drive from the pineal gland drives the habenula, which inhibits wake neurotransmitters, which inhibits motivation and action using the basal ganglia as a gate. Ongoing action sustains wake against habenula-driven sleep pressure.

The full diagram includes the wake-ignition circuit from R.pb, the sleep-sustain circuit in Po.v (Po.vl and Po.mn), and the wake-sustain circuit in H.l and V. As a reminder, this model is highly simplified and really only serves as a skeleton to organize the various brainstem sleep systems.

Cortical slow wave sleep

Although I’m trying to avoid the cortex as long as possible, studies use cortical slow waves as a sleep marker, so it’s inescapable. Cortical slow waves are globally synchronized neuron firing between around 0.5Hz to 4Hz. The slow wave firing has no information content, but the oscillations may help clear the cortex of metabolic toxins.

During wake, neurons expend to fill the intercellular space because of the neuron’s ion gradients. Filling the intercellular space means the CSF (cerebral-spinal fluid) can’t clear metabolic toxins [Xie et al 2013]. Slow wave sleep shrinks the neurons allowing fluid to fill the intercellular space, and the oscillations may even help with fluid circulation [Fultz et al 2019].

Cortical sleep appears strongly coupled to astrocytes. Astrocyte calcium precedes slow waves in the cortex [Poskanzer and Yuste 2016]. Astrocytes may even organized SWS waves across the cortex, using electrical gap junctions to connect to astrocyte neighbors [Vaidyanathan et al 2021].

The above diagram shows a simplified cortical wake circuit, although the cortex is also affected by wake neurotransmitters norepinephrine, serotonin and dopamine. In this model the cortex is mostly an appendage of the brainstem sleep circuit, waking when the brainstem wakes.

P.bf (basal forebrain) is a set of GABA and ACh nuclei that activate the cortex, hippocampus, and olfactory bulb. Although P.bf is identified by its ACh neurons, the GABA projections seem to be more important for wake.

Notes: Local cortical sleep pressure is signaled with GABA [Alfonsa et al 2023]. Parts of the cortex can sleep independently [Krueger et al 2013].

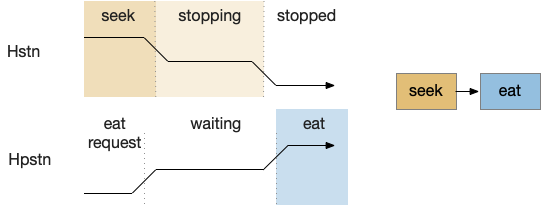

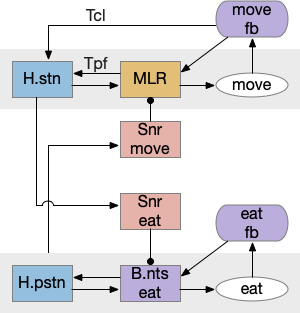

Ppt and P.ldt ACh and wake

Although I’ve lumped Ppt (pedunculopontine nucleus) and P.ldt (laterodorsal tegmental nucleus) with the “V” wake promoting areas, they deserve a special mention because of their connection and similarity with P.bf. Ppt and P.ldt are ACh ganglia near the isthmus midbrain-hindbrain boundary. Ppt is part of the MLR, showing the tight connection between locomotion and wake. Ppt feeds into P.bf, the striatum, and other locomotive regions like H.stn.

Interestingly, all Ppt neurons self-generate gamma oscillations through intrinsic channels [Garcia-Rill et al 2015]. So it could be an ignition source of gamma activation in the striatum and cortex.

References

Alfonsa H, Burman RJ, Brodersen PJN, Newey SE, Mahfooz K, Yamagata T, Panayi MC, Bannerman DM, Vyazovskiy VV, Akerman CJ. Intracellular chloride regulation mediates local sleep pressure in the cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2023 Jan;26(1):64-78.

Anaclet C, Ferrari L, Arrigoni E, Bass CE, Saper CB, Lu J, Fuller PM. The GABAergic parafacial zone is a medullary slow wave sleep-promoting center. Nat Neurosci. 2014 Sep;17(9):1217-24.

Cai P, Huang SN, Lin ZH, Wang Z, Liu RF, Xiao WH, Li ZS, Zhu ZH, Yao J, Yan XB, Wang FD, Zeng SX, Chen GQ, Yang LY, Sun YK, Yu C, Chen L, Wang WX. Regulation of wakefulness by astrocytes in the lateral hypothalamus. Neuropharmacology. 2022 Dec 15;221:109275.

Chen CR, Zhong YH, Jiang S, Xu W, Xiao L, Wang Z, Qu WM, Huang ZL. Dysfunctions of the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus induce hypersomnia in mice. Elife. 2021 Nov 17;10:e69909. doi: 10.7554/eLife.69909.

Chowdhury S, Matsubara T, Miyazaki T, Ono D, Fukatsu N, Abe M, Sakimura K, Sudo Y, Yamanaka A. GABA neurons in the ventral tegmental area regulate non-rapid eye movement sleep in mice. Elife. 2019 Jun 4;8:e44928.

Eban-Rothschild A, Rothschild G, Giardino WJ, Jones JR, de Lecea L. VTA dopaminergic neurons regulate ethologically relevant sleep-wake behaviors. Nat Neurosci. 2016 Oct;19(10):1356-66. doi: 10.1038/nn.4377. Epub 2016 Sep 5.

Erickson ETM, Ferrari LL, Gompf HS, Anaclet C. Differential Role of Pontomedullary Glutamatergic Neuronal Populations in Sleep-Wake Control. Front Neurosci. 2019 Jul 30;13:755.

Flanigan ME, Aleyasin H, Li L, Burnett CJ, Chan KL, LeClair KB, Lucas EK, Matikainen-Ankney B, Durand-de Cuttoli R, Takahashi A, Menard C, Pfau ML, Golden SA, Bouchard S, Calipari ES, Nestler EJ, DiLeone RJ, Yamanaka A, Huntley GW, Clem RL, Russo SJ. Orexin signaling in GABAergic lateral habenula neurons modulates aggressive behavior in male mice. Nat Neurosci. 2020 May;23(5):638-650.

Fuller PM, Sherman D, Pedersen NP, Saper CB, Lu J. Reassessment of the structural basis of the ascending arousal system. J Comp Neurol. 2011 Apr 1;519(5):933-56.

Fultz NE, Bonmassar G, Setsompop K, Stickgold RA, Rosen BR, Polimeni JR, Lewis LD. Coupled electrophysiological, hemodynamic, and cerebrospinal fluid oscillations in human sleep. Science. 2019 Nov 1;366(6465):628-631.

Garcia-Rill E, Hyde J, Kezunovic N, Urbano FJ, Petersen E. The physiology of the pedunculopontine nucleus: implications for deep brain stimulation. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2015 Feb;122(2):225-35.

Gazea M, Furdan S, Sere P, Oesch L, Molnár B, Di Giovanni G, Fenno LE, Ramakrishnan C, Mattis J, Deisseroth K, Dymecki SM, Adamantidis AR, Lőrincz ML. Reciprocal Lateral Hypothalamic and Raphe GABAergic Projections Promote Wakefulness. J Neurosci. 2021 Jun 2;41(22):4840-4849.

Gelegen C, Miracca G, Ran MZ, Harding EC, Ye Z, Yu X, Tossell K, Houston CM, Yustos R, Hawkins ED, Vyssotski AL, Dong HL, Wisden W, Franks NP. Excitatory Pathways from the Lateral Habenula Enable Propofol-Induced Sedation. Curr Biol. 2018 Feb 19;28(4):580-587.e5.

Grady FS, Boes AD, Geerling JC. A Century Searching for the Neurons Necessary for Wakefulness. Front Neurosci. 2022 Jul 19;16:930514.

Heiss JE, Yamanaka A, Kilduff TS. Parallel Arousal Pathways in the Lateral Hypothalamus. eNeuro. 2018 Aug 21;5(4):ENEURO.0228-18.2018.

Hikosaka O. The habenula: from stress evasion to value-based decision-making. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010 Jul;11(7):503-13.

Jones JD, Holder BL, Eiken KR, Vogt A, Velarde AI, Elder AJ, McEllin JA, Dissel S. Regulation of sleep by cholinergic neurons located outside the central brain in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2023 Mar 2;21(3):e3002012.

Krueger JM, Huang YH, Rector DM, Buysse DJ. Sleep: a synchrony of cell activity-driven small network states. Eur J Neurosci. 2013 Jul;38(2):2199-209.

Lahti L, Haugas M, Tikker L, Airavaara M, Voutilainen MH, Anttila J, Kumar S, Inkinen C, Salminen M, Partanen J. Differentiation and molecular heterogeneity of inhibitory and excitatory neurons associated with midbrain dopaminergic nuclei. Development. 2016 Feb 1;143(3):516-29.

Mogavero MP, Godos J, Grosso G, Caraci F, Ferri R. Rethinking the Role of Orexin in the Regulation of REM Sleep and Appetite. Nutrients. 2023 Aug 22;15(17):3679.

Nicola SM. Reassessing wanting and liking in the study of mesolimbic influence on food intake. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2016 Nov 1;311(5):R811-R840.

Pelluru D, Konadhode RR, Bhat NR, Shiromani PJ. Optogenetic stimulation of astrocytes in the posterior hypothalamus increases sleep at night in C57BL/6J mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2016 May;43(10):1298-306.

Poskanzer KE, Yuste R. Astrocytes regulate cortical state switching in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 May 10;113(19):E2675-84.

Saper CB, Fuller PM, Pedersen NP, Lu J, Scammell TE. Sleep state switching. Neuron. 2010 Dec 22;68(6):1023-42.

Satterfield LK, De J, Wu M, Qiu T, Joiner WJ. Inputs to the sleep homeostat originate outside the brain. J Neurosci. 2022 Jun 9;42(29):5695–704.

Tchenio A, Valentinova K, Mameli M. Can the Lateral Habenula Crack the Serotonin Code? Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2016 Oct 24;8:34.

Teng S, Zhen F, Wang L, Schalchli JC, Simko J, Chen X, Jin H, Makinson CD, Peng Y. Control of non-REM sleep by ventrolateral medulla glutamatergic neurons projecting to the preoptic area. Nat Commun. 2022 Aug 12;13(1):4748.

Tossell K, Yu X, Giannos P, Anuncibay Soto B, Nollet M, Yustos R, Miracca G, Vicente M, Miao A, Hsieh B, Ma Y, Vyssotski AL, Constandinou T, Franks NP, Wisden W. Somatostatin neurons in prefrontal cortex initiate sleep-preparatory behavior and sleep via the preoptic and lateral hypothalamus. Nat Neurosci. 2023 Oct;26(10):1805-1819.

Vaidyanathan TV, Collard M, Yokoyama S, Reitman ME, Poskanzer KE. Cortical astrocytes independently regulate sleep depth and duration via separate GPCR pathways. Elife. 2021 Mar 17;10:e63329.

Webster JF, Lecca S, Wozny C. Inhibition Within the Lateral Habenula-Implications for Affective Disorders. Front Behav Neurosci. 2021 Nov 26;15:786011.

Xin W, Schuebel KE, Jair KW, Cimbro R, De Biase LM, Goldman D, Bonci A. Ventral midbrain astrocytes display unique physiological features and sensitivity to dopamine D2 receptor signaling. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019 Jan;44(2):344-355.

Yamaguchi H, Hopf FW, Li SB, de Lecea L. In vivo cell type-specific CRISPR knockdown of dopamine beta hydroxylase reduces locus coeruleus evoked wakefulness. Nat Commun. 2018 Dec 6;9(1):5211.

Yang SR, Hu ZZ, Luo YJ, Zhao YN, Sun HX, Yin D, Wang CY, Yan YD, Wang DR, Yuan XS, Ye CB, Guo W, Qu WM, Cherasse Y, Lazarus M, Ding YQ, Huang ZL. The rostromedial tegmental nucleus is essential for non-rapid eye movement sleep. PLoS Biol. 2018 Apr 13;16(4):e2002909.

Yu X, Li W, Ma Y, Tossell K, Harris JJ, Harding EC, Ba W, Miracca G, Wang D, Li L, Guo J, Chen M, Li Y, Yustos R, Vyssotski AL, Burdakov D, Yang Q, Dong H, Franks NP, Wisden W. GABA and glutamate neurons in the VTA regulate sleep and wakefulness. Nat Neurosci. 2019 Jan;22(1):106-119.

Yu X, Ba W, Zhao G, Ma Y, Harding EC, Yin L, Wang D, Li H, Zhang P, Shi Y, Yustos R, Vyssotski AL, Dong H, Franks NP, Wisden W. Dysfunction of ventral tegmental area GABA neurons causes mania-like behavior. Mol Psychiatry. 2021 Sep;26(9):5213-5228.

Yu X, Zhao G, Wang D, Wang S, Li R, Li A, Wang H, Nollet M, Chun YY, Zhao T, Yustos R, Li H, Zhao J, Li J, Cai M, Vyssotski AL, Li Y, Dong H, Franks NP, Wisden W. A specific circuit in the midbrain detects stress and induces restorative sleep. Science. 2022 Jul;377(6601):63-72.

Zhang J, Peng Y, Liu C, Zhang Y, Liang X, Yuan C, Shi W, Zhang Y. Dopamine D1-receptor-expressing pathway from the nucleus accumbens to ventral pallidum-mediated sevoflurane anesthesia in mice. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2023 Nov;29(11):3364-3377.

Zhou F, Wang D, Li H, Wang S, Zhang X, Li A, Tong T, Zhong H, Yang Q, Dong H. Orexinergic innervations at GABAergic neurons of the lateral habenula mediates the anesthetic potency of sevoflurane. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2023 May;29(5):1332-1344.