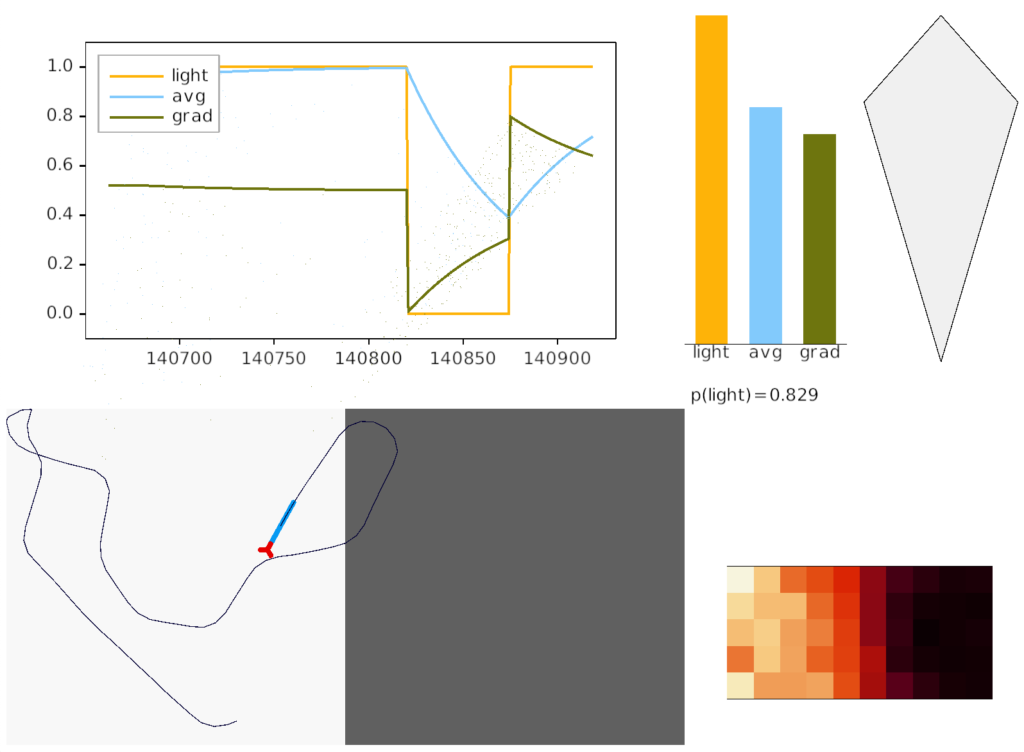

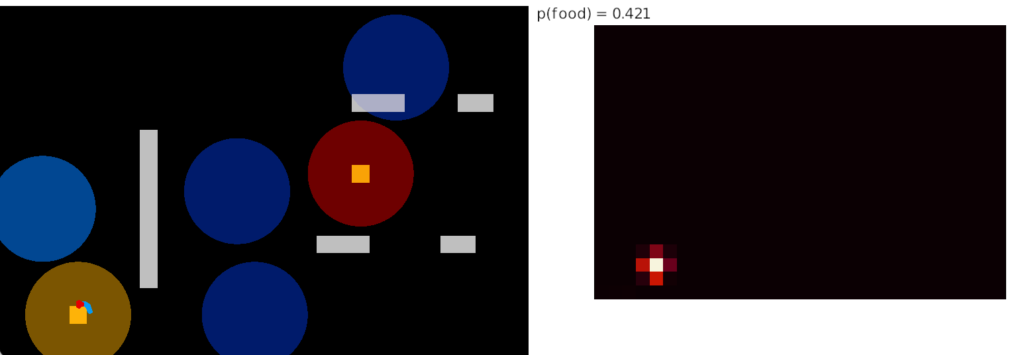

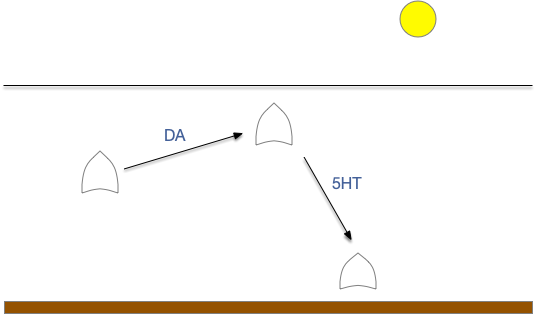

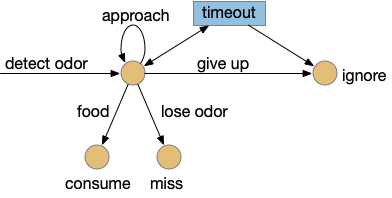

I’m looking to improve the foraging algorithm with an idea from essay 17, which suggested that when the foraging fails, the animal should avoid the failed area. The foraging task uses an odor cue to seek food. Currently when the model gives up (times out), it disables seeking, but doesn’t actively avoid the current place, but returns to the wide-ranging roaming search.

For now, I’m still avoiding memory, but consider the alternating T-maze used in rodent behavior [Deacon and Rawlins 2006]. Mice are released at the base of the T and choose one of the directions to search for food. If the experiment repeats (by picking up the mice and restarting) mice will tend to explore the unexplored end first.

But for our foraging task, let’s use the same device for a different purpose. Instead of repeating the experiment by unnatural teleportation, consider the simpler problem of foraging with this device as an environment.

When rodents are foraging and reach one end, they will reverse and search the other end. Because rodents are far more advanced than the toy model, they can remember which arm of the maze they’ve already explored. But consider a simpler sub-strategy that uses RTPA (real-time place avoidance) where the animal temporarily avoids the current area or areas associated with food. By actively avoiding the already-explored area, the animal will save time by avoiding repeated searching.

A difficulty in finding the neural correlates of RTPA is the great diversity of reasons for RTPA, and circuits even in the brainstem. There are many reasons for place avoidance:

- Startle: reflex escape

- Escape from an imminent predator

- Escape from an environment hazard (CO2, temperature)

- Avoiding innate cues (predator odors)

- Avoiding learned cues (CPA conditioned place avoidance)

- Search optimization: avoiding already searched areas

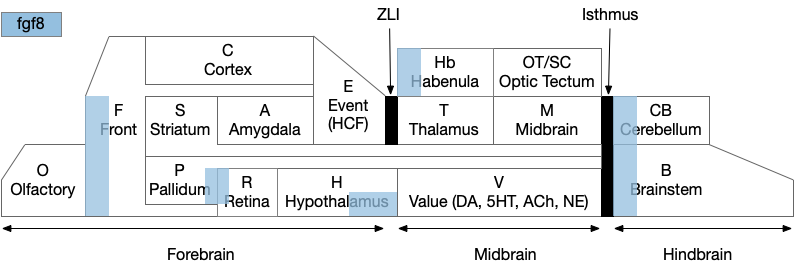

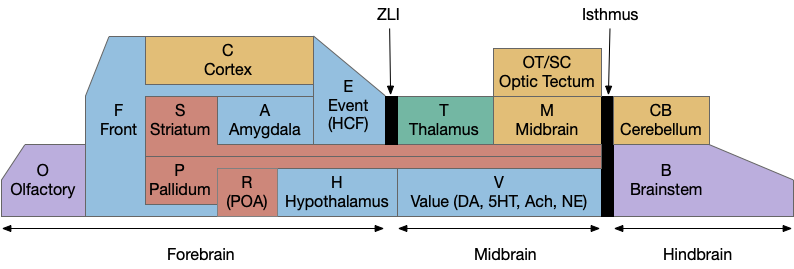

Because this topic is large and the number of circuits is also large, I’ll start with a more abstract view to provide some context for a later dive into details. The two architectures will be a set of labeled path seek and avoidance circuits, and a secondary consensus circuit to coordinate the labeled paths.

Labeled path

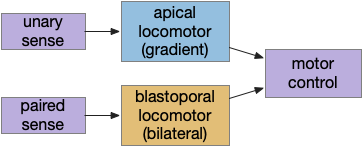

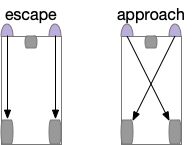

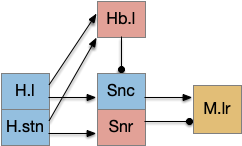

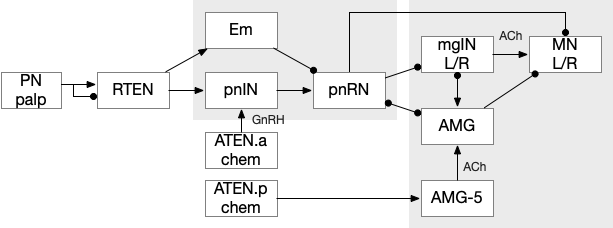

A labeled path architecture uses individual circuit paths for each behavior and sense, as opposed to bringing all stimuli into a central node with a general decision algorithm [Helmbrecht 2018]. (Helmbrecht uses “labeled line,” which conflicts with the fish “lateral line” sense.) As least to some extend, the brainstem is designed around labeled paths, which is particularly evident if using the chimera model of the bilateral brain [Tosches and Arendt 2017].

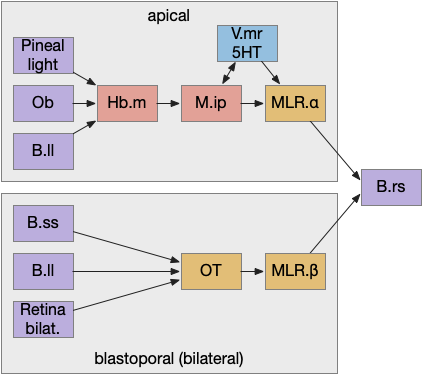

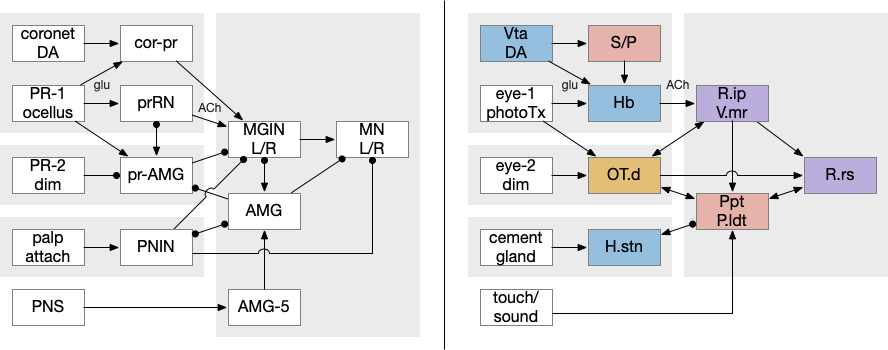

The chimera model posits that brains of bilateral animals combine features from apical (unilateral) and bilateral (“blastoporal” in their terminology because they focus on zooplankton larvae). The apical mode is associated with the front of the brain, such as the hypothalamus, and its locomotion is temporally gradient based, like the tumble-and-run of bacteria. The bilateral mode is more reflexive, turning left if touched on the right, like Braitenberg vehicles [Braitenberg 1984]. Apical systems include olfactory search and phototaxis, while bilateral touch, lateral line, auditory and bilateral vision in a second system. For zebrafish one study describes multiple paths as a “high road” through Hb (habenula, apical) and a “low road” through OT (optic tectum, bilateral) [do Camo Silva et al 2018].

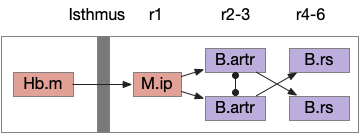

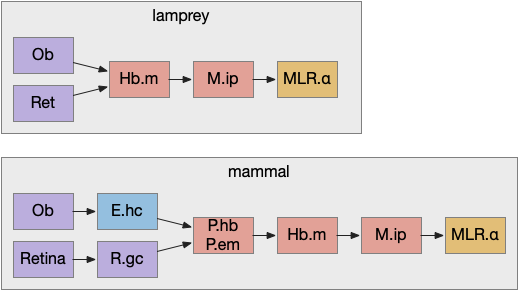

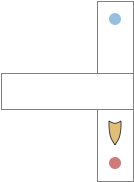

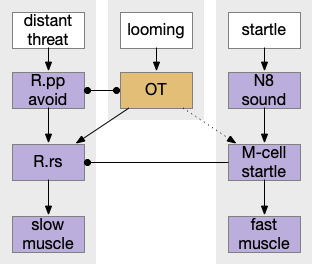

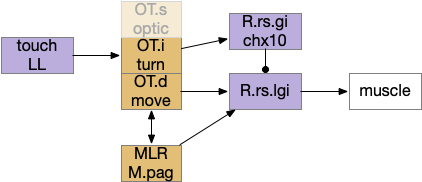

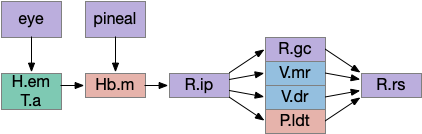

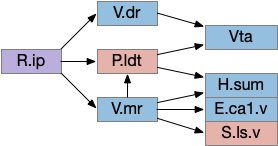

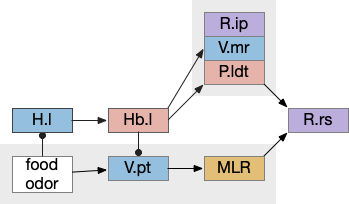

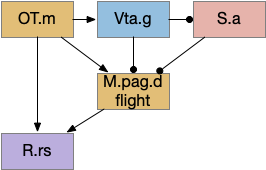

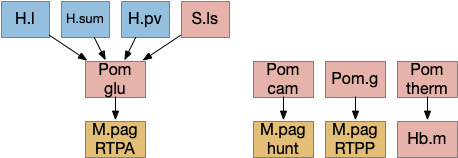

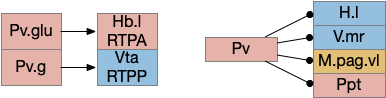

The above diagram shows some vertebrate labeled paths, which is clearer in simpler vertebrates like the lamprey and zebrafish. In the zebrafish startle reflex, a sudden noise triggers a fast C-bend turn followed by rapid swimming. The trigger can be a noise, vestibular, or lateral line motion [Berg et al 2018]. The startle circuit is only three synapses from the original sensor to the muscle, from the N8 auditory/vestibular nerve to the giant M-cell (Mauthner cell in r4) to the motor neuron that drives locomotion. In young zebrafish larva, head touch neurons (N5 trigeminal) connect to M-cells and are later replaced by N8 [Kohashi et al 2012]. M-cells fire only once per escape to drive the initial turn. Interestingly the escape turn choice uses an axo-axonic repeater and amplifier [Guan et al 2021].

In a different path looming and dimming visual signals that represent predators or obstacles drive OT (optic tectum), which can drive escape that either uses or bypasses the M-cell depending on the threat level [Bhattacharya et al 2017]. OT also pre-programs the M-cell circuit by suppressing the left or right to avoid an obstacle [Zwaka et al 2022].

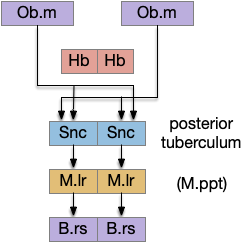

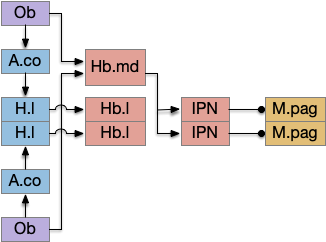

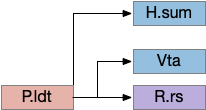

Phototaxis (seeking or avoiding light) uses a temporal gradient system composed of left Hb.m (medial habenula) and R.ip.d (dorsal interpeduncular nucleus), which projects to the R.rs (reticulospinal motor command) neurons via relays in V.mr (median raphe) and P.ldt (laterodorsal nuclei) [Chen and Engert 2014]. Food odor seeking uses the right Hb.m and R.ip.v (ventral interpeduncular nucleus) [Chen et al 2019].

In lamprey a distinct food-seeking path through V.pt (posterior tuberculum – possibly homologous to vertebrate Vta/Snc) to MLR (midbrain locomotor region) and finally to R.rs [Derjean et al 2010]. Zebrafish has a similar dual path through Hb.l (lateral habenula) through a midbrain TSN circuit [Koide et al 2018].

Slower escape uses a distinct prepontine (rhombomere r0-r1) circuit, which is suppressed by the M-cell escape circuits [Marquart et al 2019].

Some of these paths have shared elements, particularly at the motor control like MLR, but the general pattern is multiple labeled paths for each behavior. The paths already mentioned don’t include more complex food-seeking paths through the basal ganglia and hypothalamus.

Multiple labeled paths immediately raises the difficulty of coordination. How does the system juggle priorities? Even the simple startle reflex needs to be modulated because the animal shouldn’t startle if the loud sound is expected, such as near a waterfall. In contrast in a dangerous area with possible predators the animal should increase the reflex to a hair-trigger. Similarly if the threat is weak and the animal is hunting or eating and hungry, it might ignore the threat to continue eating. A second architecture, distinct from the label path, emphasizes the coordination of multiple paths, possibly using a consensus system to decide on an appropriate action.

Consensus loops

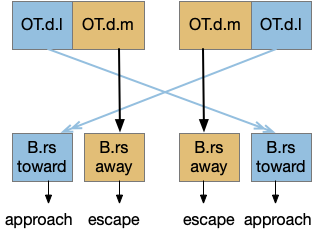

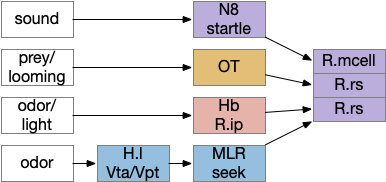

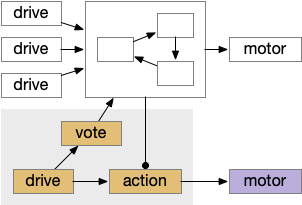

While the labeled paths have strong evidence, the consensus loop is only a thought experiment to tie the paths together. Multiple paths for food seeking and for avoiding is a distributed system, and distributed systems makes decision circuitry more complicated because they’re not central decision node. Every node needs to agree with the decision. Whether to avoid or approach needs to be agreed on by all the systems. It wouldn’t make sense for one system to believe the animal is approaching an object but another system believes the action is avoiding. Voting distributes the consensus.

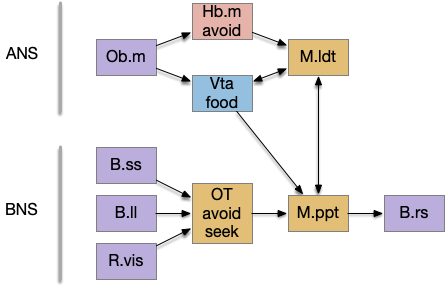

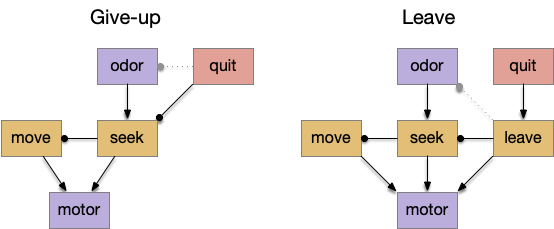

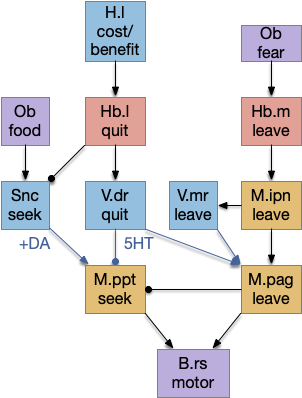

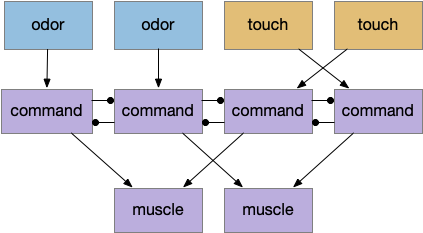

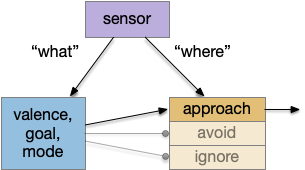

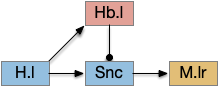

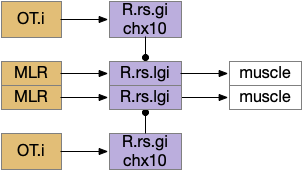

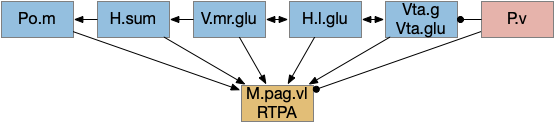

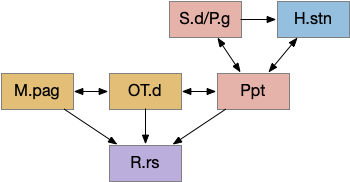

The above diagram shows the model. The different labeled paths of seeking or avoiding join a voting consensus system in a motivational look, which allows one path to drive motor output.

A single labeled path has a sense or motivation drive that tries to act on motor output, but is inhibited by the consensus system. For example, if a predator odor arrives, the odor avoidance path votes to enable its own locomotion. If the consensus system agrees, it will disinhibit the odor avoidance path, letting the animal escape. Note that a high priority threat could bypass the consensus system.

Seek and avoid consensus system

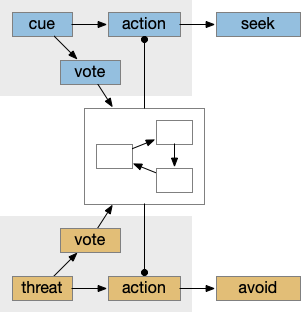

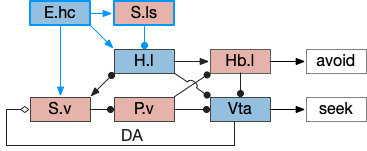

This system can manage conflicts between seek and avoidance, such as animals continuing to eat if a predator threat exists but is low. Consider a simplified consensus system with only one seek node and one avoid node, using the consensus to select one when there’s a conflict.

If there’s a food cue and no conflicting threats, the food vote passes easily and the animal seeks the food. Similarly a predator odor with no conflict will enable avoidance. If there’s a conflict, the system can weigh the costs and benefits of the threat and the food, possibly depending on hunger state or a more sophisticated threat assessment.

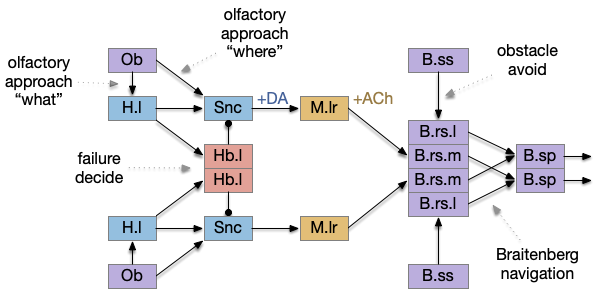

Keeping these general ideas of the labeled path and consensus systems in mind, let’s start working through several specific paths. The end goal is to organize the main brainstem locomotive areas into a simplified, unified model. The two major paths will be apical paths through Hb (habenula) using temporal gradients (klinotaxis) [Chen and Engert 2014] and bilateral paths through OT (optic tectum) using spatial gradients (tropotaxis).

Apical and bilateral avoidance

Because there are many labeled paths, dividing them up might help organize the model. An early division between labeled paths goes back to the bilaterian (worm-like, slug-like) ancestors, which added bilateral, dual-sensory navigation (tropotaxis, spatial gradient) to an older single-sensor navigation that used the animal’s movement to choose a direction (klinotaxis, temporal gradient), such as the simple tumble-and-run that even bacteria and simple radial zooplankton use for seeking odors (chemotaxis) and seeking or avoiding light (phototaxis). This chimera hypothesis [Tosches and Arendt 2013] considers bilateral animals as a fusion between the locomotive systems. The apical zooplankton larvae of bilaterian worms may have been a secondary development to escape predation [Mallatt 2021]. In vertebrates, apical klinotaxis is implemented by Hb (habenula) temporal gradient seeking and H.l (lateral hypothalamus) motivation. Bilateral tropotaxis navigation is implemented by several labeled path systems, typified by OT (optic tectum) and the M-cell start reflex.

A primitive apical example is the helical phototaxis of many annelid (marine worm) zooplankton larvae, and a primitive bilateral example is the mollusk sea slug navigation.

Zooplankton apical phototaxis

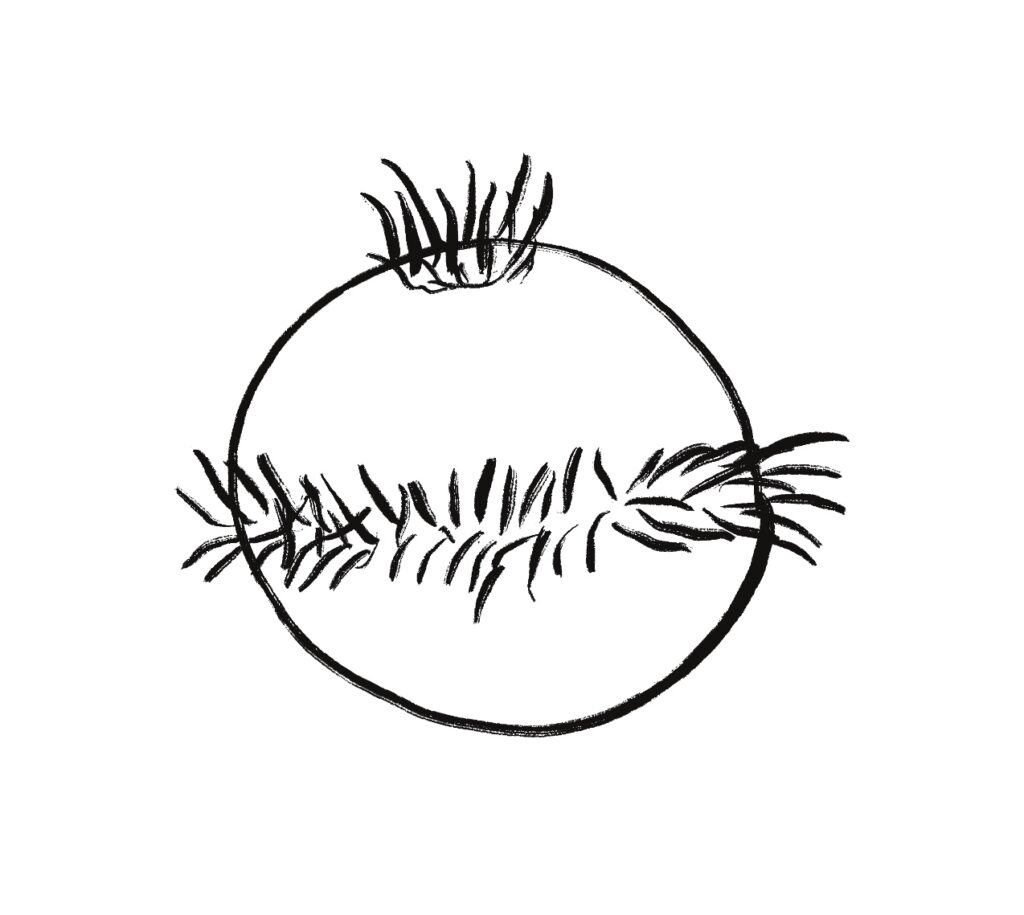

One type of zooplankton is essentially a globe with a fringe of cilia and an apical tuft for chemical processing, such as the Platynereis larva.

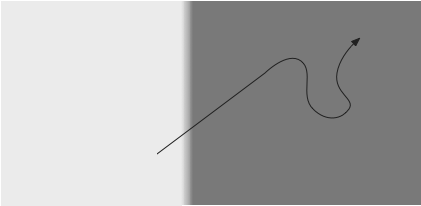

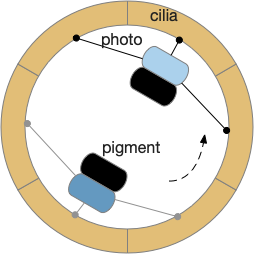

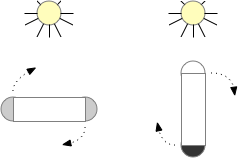

Phototaxis for this larva depends on its helical movement (helical klinotaxis). As it moves forward, the larva also rotates and wobbles, which means that parts of the equatorial band are nearer the light or further from the light depending on the rotation. If the upper cilia halt, the larva will steer toward the light. If the lower cilia halt, the larva will steer away from the light [Randel and Jékely 2016].

The system depends on a directional eye, which uses a photoreceptor and a pigment cell that imposes directionality by shading the photoreceptor, because other cells of the larva are transparent. The photoreceptor compares the current brightness to its average brightness as the larva rotates. If it’s brighter than average, then it must be facing the light, and will signal the cilia to briefly halt, using ACh (acetylcholine) as a neurotransmitter. This trivial one-neuron circuit is sufficient for simple phototaxis [Randel and Jékely 2016].

Although this example larva uses two photoreceptors, it’s not truly bilateral and the two photoreceptors don’t communicate. Ablating one photoreceptor doesn’t abolish phototaxis, although it does reduce efficiency. Using three or four photoreceptor/pigment pairs would work, as well as removing all but one. This system is apical klinotaxis, not bilateral tropotaxis, which makes sense because the above zooplankton is not bilateral. While this zooplankton uses helical klinotaxis, another common form of klinotaxis is a side to side “casting” motion used by other simple animals like c. Elegans [Izquierdo and Lockery 2010].

If zooplankton phototaxis is an example of apical navigation, then the mollusk sea slug is an example of bilateral navigation.

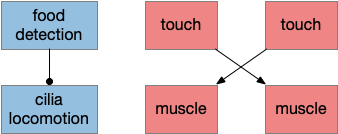

Mollusk sea slug seek and avoid

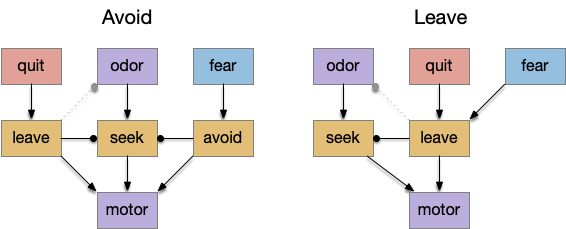

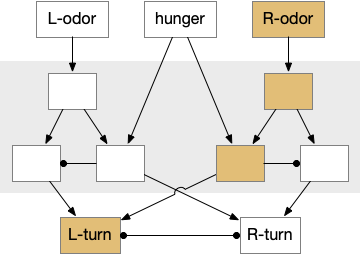

The mollusk sea slug circuit is a pure bilateral circuit, almost directly a Braitenberg circuit [Braitenberg 1984], discussed in essay 14. The following shows a rough schematic of the sea slug seek and avoid. This circuit is interesting because with only a few neurons, the slug can switch from turning toward a food odor when hungry to turning away from the odor when not hungry [Gillette and Brown 2015].

In the diagram above, the central grey area is a switchboard circuit. Hunger reconfigures the switches connecting the odor to the turn motor neurons. When the slug is hungry, the right odor sensor connects with the left turn muscle, seeking the odor. But when the slug is sated, the right odor sensor connects with the right turn muscle, avoiding the odor. When the slug is hungry, it approaches food but when it’s not hungry, it avoids food odor cues.

A similar animal with a different circuit configuration uses serotonin to switch from avoidance to approach [Hirayama et al 2014].

For the goal of this essay, avoiding a failed food cue, this circuit is perfect because when the animal finds a false cue, it reversed movement from seek to avoid, which exactly fits the essay needs. Unfortunately, the vertebrate circuits aren’t nearly as straightforward. As a start for the vertebrate navigation paths, the startle reflex managed in vertebrates by the giant Mauthner cells is a simple starting point.

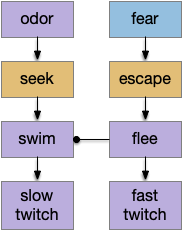

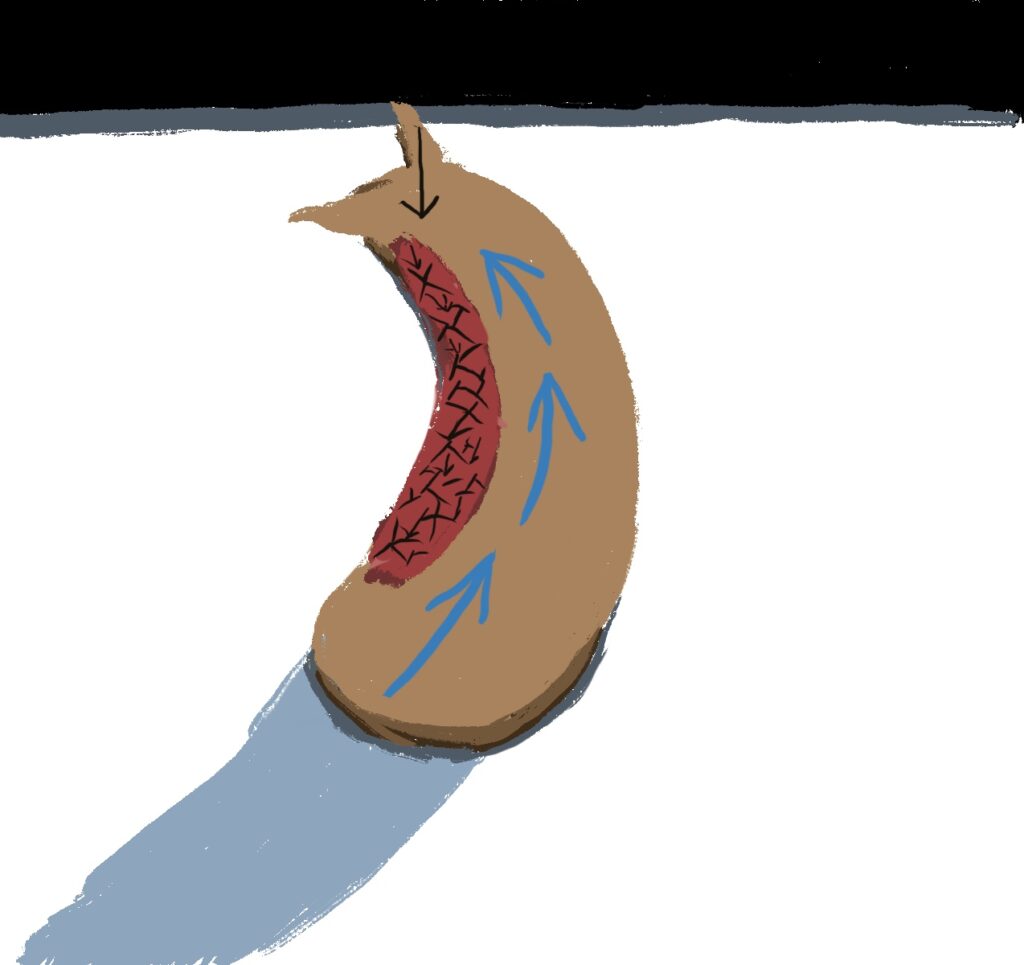

Amphioxus fast twitch reflex

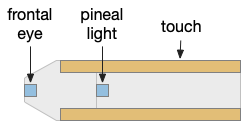

The fast twitch startle reflex is a clear example of a bilateral labeled path avoidance circuit. A noxious sense on one side causes a fast turn away from the sense. The sense can be a touch on the head, such as running into an object, or a loud sound or a vestibular imbalance signal. This circuit predates vertebrates and a similar circuit exists in amphioxus, a filter-feeding chordate that looks something like a fish without a distinct head and without eyes, but with several photoreceptors including a frontal “eye.”

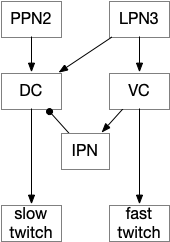

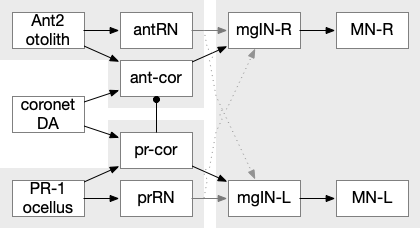

In amphioxus the startle reflex drives fast twitch muscle fibers, where normal swimming uses slow twitch fibers [Lacalli and Candiani 2017]. This circuit path is entirely distinct even to using the different muscles. The following diagram shows part of the amphioxus motor control circuit. (Because the neuron names are specific to amphioxus, they’re not hugely important for this essay.)

The diagram shows the LPN3 (large paired neuron) fast twitch escape path, and the PPN2 normal swimming match, including intermediary motor control neurons [Lacalli and Candiani 2017]. This amphioxus escape circuit resembles the zebrafish Mauthner cell escape.

Zebrafish Mauthner cell escape

Zebrafish have a pair of large M-cell (Mauthner cell) neurons that are specialized for auditory and vestibular startle escape. These are very fast reflexes on the order of 10ms, which can be modulated by higher context [Zwaka et al 2014] including OT. Although the M-cells perform a similar role to the amphioxus LPN3, it’s not clear that they’re homologous, which requires common descent, because the large escape neuron is a common pattern in non-chordate systems.

The primary input to M-cell escape is an auditory and vestibular signal from N8 (8th cranial nerve is auditory and vestibular). In water, sound and primitive vestibular sense have some similarities, because water motion produces not just sound but animal motion, depending on the frequency. The M-cell directly connects to motor neurons to muscles. The startle escape is only a three neurons and a clear, distinct labeled path.

A second zebrafish threat avoidance path uses neurons in R.pp (pre-pontine r0-r1) [Marquart et al 2019] for more distance threats. Unlike the M-cell circuit, this R.pp path is more than a reflex, but it’s still a hardwired path. A third threat circuit uses OT (optic tectum), for example the looming response. Most vertebrates will flee or freeze from a rapid and overhead expanding dark object, representing a potential predator or an obstacle. The mammalian startle circuit shares similarity with an acoustic projection to R.pn.c (caudal pontine reticular) neurons, in an analogous area to the M-cell [Kim et al 2017].

Some of these circuits do share sub circuits. For example, hindbrain locomotion and turning are distinct circuits that are used by both bilateral and apical avoidance circuits.

Hindbrain locomotion and turning

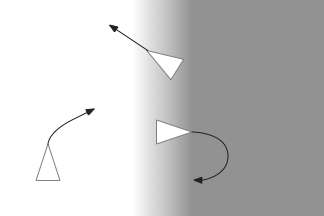

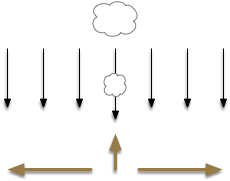

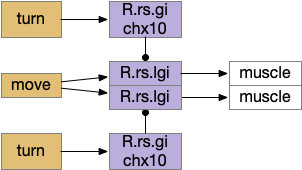

Senses are not the only source of distinct paths because actions can be split into parts like a car’s divided steering and acceleration. In vertebrates, accelerating and turning use distinct hindbrain circuits. Although both MLR (midbrain locomotive region) and OT.d (deep layer of the optic tectum) encode seeking and avoiding, they don’t encode left or right turns. Activating the left or the right MLR produces straight movement [Brocard et al 2010]. Turning is managed from OT.i (intermediate layer of the optic tectum) to distinct R.rs motor command neurons, marked by the chx10 transcription factory [Cregg et al 2020].

The above diagram shows the basic idea. The upstream MLR can command forward movement without specifying details, because swimming is an oscillatory process with CPG (central pattern generators) in the spinal cord and the hindbrain. To turn, the chx10 neurons inhibit the swimming stroke in one direction [Cregg et al 2020], similar functionally to the apical zooplankton inhibition of cilia for phototaxis.

Splitting out turning can simplify the system by dividing labor, where OT.i is always responsible for obstacle avoidance, but a diverse set of labeled paths decode whether to seek or to avoid.

Optic tectum and dimming

The OT is named after its retinotopic visual map that is used for avoiding looming/dimming obstacles and predators, and also for seeking prey [Basso et al 2021]. For most vertebrates, OT is the primary visual area, and the visual cortex only provides abstract context, and amphibians and fish lack a proper visual cortex [Heap et al 2018]. For this essay, OT is less important for its sophisticated visual organization, but more because it also contains motor maps for seeking or prey and avoidance of looming objects, and dimming fields. Its motor map also contains drinking and licking [Liu et al 2022].

OT processes looming and dimming objects and avoids them. Since the essay’s model lacks proper vision, the dimming is currently most important. Because OT also has obstacle avoidance, it’s a more sophisticated system than simply reflex. It’s likely that other avoidance systems will use OT for obstacle handling. Even in the case of the M-cell reflex, the OT.i pre-programs the M-cell, to avoid obstacles in case of a future startle [Zwaka et al 2014].

Optic tectum and turning

This division between turning and acceleration applies to OT itself. OT is a layered structure where the top layer is a visual map, the intermediate layer integrates other senses and produces turns, and the deepest layer includes actions such as avoiding and seeking [Liu et al 2022]. OT.d (deep OT) is a motor area for seek and avoid, connected with MLR and M.pag (periaqueductal grey) motor output, and integrates general dimming from the retina with distinct expansion calculation in OT itself [Heap et al 2018], to avoid looming objects. OT.i (intermediate OT) includes multi sensory integration and turning motor area, connected with LL (lateral line) electro sensation and water motion, somatosensory (whiskers in mice), auditory input from M.ic (inferior colliculus) and optic input from OT.s (superficial OT).

Because only the top layer is specifically optic, some neuroscientists use “tectum” (roof in latin) instead of OT to emphasize its multi sensory and motor function, not just the optic features. On argument suggests that the optic layer OT.s is a secondary layer, added to a more primitive OT.i and OT.d that are more connected with reticular areas like MLR and M.pag [Edwards 1980], [Basso et al 2021]. With that argument, OT is primarily a moving and turning structure, receiving turning and moving input from touch, lateral line, primitive dimming, and other directional senses and combining with seek and avoid decisions. When the visual system developed enough detail to support crude images like looming disks or moving prey-like dots, the OT integrated vision into its top layer.

On the other hand, since OT.d receives dimming information from H.lg (central lateral geniculate nucleus) for looming escape [Heap et al 2018], it’s also conceivable that the base OT function is visual escape from dimming, where the later expanding, looming visual processing is an optimization.

This separation of obstacle avoidance turning from seeking and avoiding greatly simplifies some other circuitry that doesn’t need to duplicate the obstacle avoidance. Since other circuitry from the apical path, like the Hb-R.ip (habenula – interpeduncular nucleus) has its own turning system, OT.i doesn’t have a monopoly on turning. But even in that case, OT.i obstacle avoidance can inform apical navigation.

Some of these avoidance circuits are from the bilateral part of the chimera, such as the M-cell and the looming OT circuits, and others are from the apical part, such as Hb.m phototaxis, chemotaxis, and thermotaxis. So, let’s now more from the bilateral avoidance circuits, explore the vertebrate apical navigation.

Tunicate helical swimming and phototaxis

Tunicates (including sea squirts) are the closest chordates to the vertebrates, but because they have evolved at a greater rate and in specialized directions, comparison with vertebrates is difficult [Stolfi and Brown 2016]. Ascidian tunicates (sea squirts) have a mobile tadpole stage that plants itself in under 24 hours and transforms into a sessile filter feeder, reforming the entire brain. In general, neuroscientists believe amphioxus more resembles the ancestral vertebrate, and that ascidians have lost too many ancestral structures for a reasonable comparison [Holland 2016]. But for the sake of exploration let’s run through a thought experiment as if the ascidian larva is a compressed and simplified version of the vertebrate ancestor, although possibly only the vertebrate larva.

Specifically, consider phototaxis in the apical helical klinotaxis mode that follows a temporal gradient, since both amphioxus and ascidian larva swim in a helical pattern. Even bacteria can follow odor gradients [Hengenius et al 2012] and as discussed above zooplankton phototaxis can move toward light with only a single photosensor [Randel and Jekely 2016]. Both amphioxus and ascidian larva have single unpaired eyes, amphioxus as a single frontal eye [Lacalli 2022] and ascidians with an asymmetrical eye paired with a second pigment cell used for geotaxis as a primitive vestibular sense [Hoyer et al 2024]. In both cases, the “eye” is directional with a pigment cell, but a non-image-forming collection of photoreceptors. The ascidian asymmetrical eye works because the ascidian tadpole swims in a helical pattern so the timing of the light on the eye matters more than its position [Ryan et al 2016].

Ascidian larvae swim in a helical pattern comprised of unilateral tail flicks and symmetrical swimming [Ryan et al 2017] and use the asymmetry of the photoreceptor and photopigment to swim toward light [Mast 1921], [Zega et al 2006]. Since helical swimming doesn’t need stabilizing fins or vestibular systems to manage roll, yaw, and pitch with 3d swimming, it’s available to evolutionarily simpler systems. Another advantage of helical phototaxis is that the photoreceptors are auto-calibrating by simply averaging the light in a rotation and requires less circuitry than a bilateral comparison of light [Randel and Jekely 2016].

However, unlike the trivial zooplankton circuit that directly connected the photoreceptor to arrest the cilia, ascidian larvae need to modulate the bilateral swimming in the primitive hindbrain, timing the muscle inhibition to achieve the same effect.

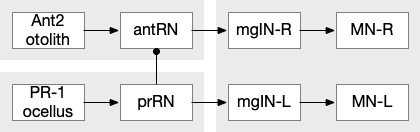

The ascidian ocellus (“eye”) has two types of photoreceptors with distinct responses. Type 1 has a pigment and lens and is directional (37 cells), while type 2 is non-directional (no pigment partner) [Salas et al 2018]. If the pigment is genetically deleted, the animal can’t use phototaxis but does respond to dimming with an escape response. In other words, the dimming response and phototaxis use distinct labeled paths with distinct input neurons [Kourakis et al 2019]. The following shows the circuit for the type 1 photoreceptors for phototaxis, where the boxes represent single neurons or small collections (5-8) of neurons, not large functions (from [Ryan et al 2016]).

The above diagram shows both geotaxis and phototaxis circuits, which are specific to right or left motor neurons respectively, because the ascidian larva neuron circuits are highly asymmetrical. Ascidian larva geotaxis swims upward and phototaxis swims away from light, generally downward. The combination encourages swimming to the underside of ledges, such as the underside of boats and harbor piers [Ryan et al 2016]. Because of the helical swimming, the left and right motor neurons aren’t left or right turns, but turns toward or away from the target. Although this circuit is more complicated than the purely apical zooplankton because of the interface to bilateral swimming, the helical swimming keeps the circuit relatively simple.

The above partial circuits are complicated by the coronet cells, another sensory cell that are paired with the photoreceptors, but with unknown function. The circuit connectivity is interesting, because coronet cells modulate both the phototaxis and geotaxis paths, but aren’t a path of their own. The phototaxis and geotaxis relay neurons above are partially bilateral. Only 70% of their connectivity is to the main side, but 30% of the connectivity is to the opposite side. In contract, the coronet-enabled neurons are 100% to the main connection [Ryan et al 2016].

As a thought experiment (unsupported by scientific evidence) the main phototaxis path might be uncertain and stochastic, while the coronet-enabled path would be a certain, deterministic connection. If the coronet cells measured the certainty of the animal’s current direction, it could encourage sticking to the current path. For example, if the coronet cells were food-odor gradient sensors, they could fire when the animal was heading toward food, enabling a chemotaxis based on modulation of geotaxis and phototaxis.

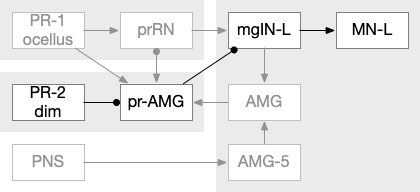

Tunicate dimming response

The ascidian dimming response triggers locomotion with a strong turn as an escape response to predators [Kourakis et al 2019]. Unlike the phototaxis photoreceptor, the dimming photoreceptors are non-directional because’er not shaded by the pigment cell. There are 23 type-1 directional photoreceptors and 7 type-2 non-directional photoreceptors for dimming.

The above diagram shows the dimming path in context with the previous phototaxis path. Like the phototaxis path, the dimming path starts from the type-2 photoreceptors to a relay neuron and to the control neurons in the motor ganglion. Unlike the phototaxis path, the dimming path is modulated by ascending motor signals from AMG (ascending motor ganglion) and from the phototaxis path [Ryan et al 2016], presumably so the normal helical phototaxis doesn’t trigger a dimming response.

Cement gland and attachment

The ascidian larva hatches before dawn, swims upward for a few hours because geotaxis is enabled before phototaxis neurons attach, and then swims away from the light, settling on a lively rock, preferring a ledge to settle under if possible. Larva do not feed [Ryan et al 2016]. The larva will attach with a cement gland on the front of its head, a trio of palms, and then transforms into the adult sessile filter feeder. The palp sensors trigger the attachment circuit, which stops all swimming and begins the metamorphosis [Anselmi et al 2024].

Although the full details of the above circuit [Ryan et al 2016] aren’t critical, the PN (palp neuron) senses the animal bumping into a rock modulated by chemical senses that avoid toxic area, and triggers a swimming shutdown by inhibiting the motor neurons and interneurons [Hoyer et al 2024]. Like the previous diagrams, the boxes represent individual neurons or small group, not large functional regions.

While the ascidian cement gland is permanent, several fish [Pottin et al 2010] and amphibians [Rétaux and Pottin 2011] have a homologous cement gland used for larvae, not adults. For example, frog tadpoles can attach to the bottom of leaves or to the water surface to avoid predators until they are large enough to hunt [Jamieson et al 2000], [Yoshizawa et al 2008]. Because of the widespread cement gland among many fish species and amphibians as well as the tunicates, it’s likely the original vertebrates had a similar cement gland [Rétaux and Pottin 2011]. Whether the gland was larva-only like in vertebrates or also used for adults as in tunicates is unknown. In either case, the cement gland circuit that inhibits locomotion must have been part of the original vertebrate.

Vertebrate analogies to the ascidian circuits

Because the ascidians are so specialized and reduced from the common ancestor with vertebrates, including major losses in genes, cells and structures, comparing the two is essentially impossible to be homologous (shared descent) [Holland 2016]. However, for the sake of exploration, I’m ignoring that advice, and looking for analogous vertebrate circuits to the ascidian larva.

The ascidian behavior each have distinct circuit paths that mostly only come together at the motor control neurons. The exception is the feedback from the AMG (ascending motor ganglion) neurons, which do feedback to the midbrain neurons, but the main paths are separate forward paths. Each of the geotaxis, phototaxis, dimming, cement gland attachment, and bilateral escape are circuit paths that are distinct until the motor command neurons.

A vertebrate analogy to the ascidian phototaxis gradient path might be the path from the retina to Hb.m (medial habenula) to R.ip (interpeduncular nucleus) and V.mr (median raphe), which then project to R.rs (reticulospinal motor command). Like the ascidian path, the Hb-R.ip phototaxis path is relatively isolated from the other paths, although Hb.m does receive large modulation from the hypothalamus. Although R.ip is mostly descending, like ascidian mgIN, V.mr is both ascending and descending like mgIN and AMG.

The dimming path from the type-2 photoreceptors resembles the dimming input to the vertebrate OT (optic tectum). Although existing vertebrates have more sophisticated eyes that can distinguish expanding objects, the dimming input to OT is still important and used for escape directionality [Fotowat and Engert 2023], [Heap et al 2018]. Retina dimming cells reach AF6 and AF8 [Temizer et al 2015], which are thalamic arborization fields before reaching OT.d. Although more complicated expanding looming response in vertebrates is better studied, expansion detection requires an image-supporting eye, and OT.d receives the simpler dimming input. Like the ascidian dimming pr-AMG (photoreceptor – ascending motor ganglion) neuron, OT.d receives multiple ascending and descending inputs that modulate the dimming response. In particular Ppt (pedunculopontine nucleus) and P.ldt (laterodorsal nucleus) both receive OT.d output and forward to R.rs, functionally similar to mgIN (motor ganglion interneuron), and send ascending feedback from R.rs to OT.d, resembling the AMG (ascending motor ganglion) functionality.

Because the cement gland exists in vertebrates, the circuit should be available, and studies do show that N5 (head touch trigeminal nerve) innervates it automatically [Pottin et al 2010], but I haven’t read any study that says this this specific group of trigeminal neurons connects to. As a through experiment, consider H.stn (subthalamic nucleus) as a choice for the cement gland, because H.stn halts ongoing action, and because H.stn receives direct input from C.i (insular cortex) and C.ss (somatosensory cortex), which are more sophisticated versions of the chemo / mechanosensory palp neurons.

The coronet path enhances taxis confidence, reducing stochastic choice, and is a set of dopamine neurons. The striatum circuit and dopamine’s role has a similar function. Without dopamine, the basal ganglia suppress weak input, and allow stochastic action. With dopamine, the basal ganglia suppresses the randomness and keep action on track. This path resembles rheotaxis food seeking, where a fish approaches a food odor by swimming upstream [Coombs et al 2020]. The “what” signal (odor) differs from the “how” signal (water current cues). Like rheotaxis, the coronet cells enhance the existing phototaxis and geotaxis, reducing the default stochastic noise.

Hb.m Medial habenula

Of the ascidian labeled paths above, the Hb (habenula) phototaxis path will be a useful anchor for the upcoming consensus circuit. Like the ascidian asymmetrical phototaxis neurons, the vertebrates Hb.m (medial habenula) is also governed by Nodal asymmetry [Roussigne et al 2009], where Nodal is a developmental genetic transcription factor. In zebrafish the left Hb.m support phototaxis, and the right Hb.m supports chemotaxis [Chen et al 2019]. Hb.m phototaxis receives both “on” and “off” neurons from the retina with a relay either in H.em (pre thalamic eminence) [Zhang et al 2017] or T.a (an area in the anterior thalamus) [Cheng et al 2017], where the connections are debated. Although Hb.m does receive dimming input from the adjacent photoreceptive pineal gland, the retina photoreceptors are more important for phototaxis [Dreosti et al 2014].

As an anatomical note, the zebrafish Hb.m is actually dorsal and therefore named Hb.d. Similarly the zebrafish Hb.m is ventral and named Hb.v, but as a simplification I’ve used the mammalian name.

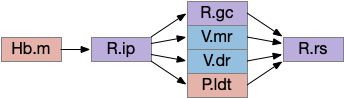

The output path from Hb.m is through R.ip (interpeduncular nucleus), which projects to several areas including R.gc (pontine central era), V.mr (median raphe – serotonin), V.dr (dorsal raphe – serotonin), and P.ldt (laterodorsal nucleus – ACh) [Quina et al 2017]. The V.mr glutamate and GABA neurons may be more important for this circuit than the serotonin neurons, which they outnumber. Also, note that V.mr is located in the same hindbrain rhombomeres (r2-r5) as some of R.rs, but are more ventral, and are reciprocally connected. In other words, V.mr is highly action and motor associated.

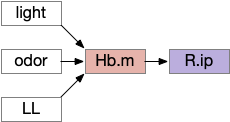

As described above, the Hb.m-R.ip path is a klinotaxis path for phototaxis [Chen and Engert 2014], chemotaxis and thermotaxis, where the klinotaxis is temporal from the animals movement, but not the helical movement of the ascidian larvae. The Hb.m-R.ip klinotaxis has multiple inputs for lamprey, including light, odor, and lateral line (water movement) [Stephenson-Jones et al 2011].

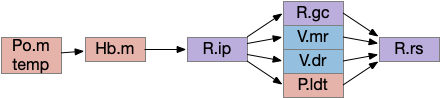

Although I’ve focused on Hb.m as an avoidance gradient circuit, it’s also a food odor seeking circuit [Chen et al 2019]. The Hb.m klinotaxis for light and odor also applies to temperature, using input from Po.m (medial preoptic nucleus) [Palieri et al 2024] and social seek and avoidance [Okamoto et al 2021], [Chou et al 2016].

Because Hb.m has several sub-nuclei and genetic clusters, it likely represents different labeled paths, supporting multiple distinct seek and avoidance paths. A binary seek vs avoid circuit is likely an oversimplification, because studies have found at least 5-6 olfactory Hb.m clusters in the larval zebrafish [Jetti et al 2014], [Beretta et al 2014]. Hb.m is asymmetrical, like the ascidian larva. Odors from either olfactory bulb activate the right Hb.m [Chen et al 2019]. Hb.m neurons have at least 262 neuropeptide receptors [Ables et al 2023] as well as morphine receptors [Gardon et al 2014], [Boulos et al 2020] including neuropeptides modulating hunger or social motivation from hypothalamic areas like H.l and H.pv.

R.ip interpeduncular nucleus

Since I’ve already covered some of the R.ip klinotaxis function in essay 24 and essay 25, I’m going to focus on the R.ip connectivity, particularly the ascending connectivity. R.ip descending efferents don’t target R.rs directly, but instead use intermediaries like R.gc (pontine central gray), V.mr (median raphe) and P.ldt (laterodorsal tegmental area) [Lima et al 2017], [Quina et al 2017].

The ascending afferents of R.ip also work through intermediaries, particularly P.ldt and V.mr [Quina et al 2017], although other connectivity studies report R.ip as directly producing ascending connectivity [Lima et al 2017]. Because V.mr is directly caudal to R.ip, the disagreement is essentially about the boundaries between R.ip and V.mr.

The ascending R.ip connectivity will become important in the next section on the consensus circuit because it completes the consensus loop, where other labeled path connectivity is descending. The ascending role is analogous to the ascidian AMG (ascending motor ganglion) neurons. For a consensus circuit to work, all nodes need to be informed of the consensus decision.

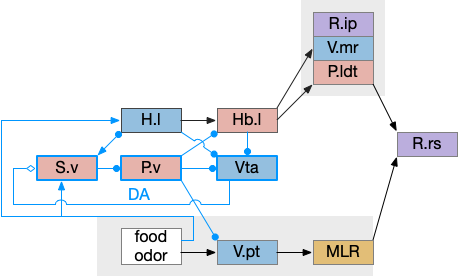

Consensus circuit narrative

Let’s now consider the consensus circuit and how it might develop from a strict labeled path system. This is just a thought experiment as a narrative explanation for the Hb.l (lateral habenula) system.

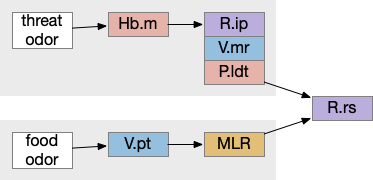

For simplicity, let’s restrict the narrative to apical systems only, ignoring bilateral systems like OT, and let’s start from a labeled path system. In the lamprey, odor information from Ob (olfactory bulb) splits into multiple paths. One path reaches Hb.m directly and another contacts V.pt (posterior tuberculum), considered a homologue of Vta / Snc (substantia nigra pars compacts), which then contacts MLR in lamprey [Derjean et al 2010] and zebrafish [Kermen et al 2013].

In this example, these two paths are distinct with threat odors going through the Hb.m – R.ip circuit and using P.ldt as an apical version of the MLR (which in lamprey may not be distinct from Ppt MLR, since the lamprey doesn’t have distinct Ppt, P.ldt and M.cnf (cuneiform nucleus)). The animal seeks food using the V.pt to MLR path.

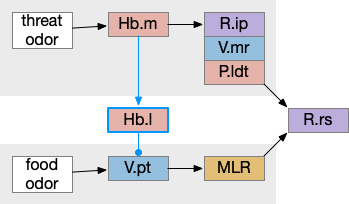

These two system can come into conflict. For the above simple system, suppose conflicts are resolved in R.rs itself, as a hard-coded priority where threats always win. But now consider a system where the conflict is resolved earlier in the stream by adding Hb.l as a lateral inhibition relay.

As a first step consider lateral inhibition of threat odor suppressing food seeking. Here the lateral inhibition path uses a relay from Hb.m to Hb.l [Gouveia and Ibrahim 2022] in a primitive Hb.l that then suppresses the V.pt path. This lateral inhibition duplicates the earlier lateral inhibition in R.rs, but is more specific because it inhibits earlier in the two paths.

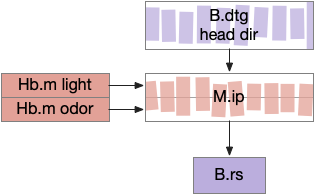

In the above diagram, the blue lines represent new connections. Notice the gating pattern for V.pt resembles the gating for the consensus circuit where the action nodes are V.pt and V.mr. Hb.l then becomes the vote accumulator for the consensus circuit. Also notice the similarity with the sleep model from essay 29, where Hb inhibits food seeking for sleep. An alternative narrative might repurpose the sleep inhibition into a path inhibition [Hikosaka 2010].

Both Hb.l and Hb.m are tonically acting, meaning that without any input their resting output is a middle value, not a binary output. This means Hb.l can gate V.pt seek and also gate its opposing avoidance circuit in V.mr and P.ldt.

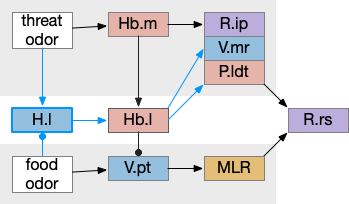

For the next step, let’s add both a bidirectional selection and also add some internal state management, because the animal shouldn’t seek food if it’s sated.

H.l hunger modulation

H.l (lateral hypothalamus) has access to hunger and satiety information by sensing blood levels directly and from connections from R.pb (parabrachial), which has signals from the digestive system via N10 vagus nerve through R.nts (solitary tract nucleus). When Ob (olfactory bulb) senses a food odor , H.l can modulate it with the current hunger sense. This means H.l as gating input to Hb.l is more effective than the simple lateral inhibition from Hb.m If the animal is sufficiently hungry, it might ignore weak threats. Note the similarity to the mollusk sea hare circuit, where hunger changed food odor from seeking to avoidance depending on the internal state.

In addition to hunger, other internal states can modulate Hb such as hypothalamic threat signaling ([Wagle et al 2022]. This step also adds control of the threat path, taking advantage of the Hb.l tonic activity to either inhibit food seeking or threat avoidance.

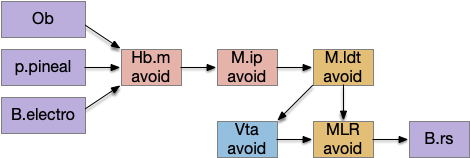

Place avoidance without a threat

Suppose we take the above circuit, but ignore or disable the threat avoidance path via Hb.m. Even without the threat path, there is an avoidance path from Hb.l to V.mr and P.ldt, where Hb.l not only disinhibits threat avoidance, but can produce place avoidance without a threat.

The above diagram shows deletion of the threat path, while retaining the abstract place avoidance path. If place avoidance is triggered, the animal will avoid the current location without needing a specific threat to avoid. This means that H.l stimulation by itself can trigger real-time avoidance [Stamatakis et al 2016]. In mammals the H.l to Hb.l connection has at least 6 clusters [Calvigioni et al 2023], which suggests multiple paths even in the abstract place avoidance.

S.v ventral striatum digression

This model of the seek vs avoid circuit can be extended to S.v (ventral striatum aka nucleus accumbens) and P.v (ventral pallidum). Consider S.v / P.v as a generalization of H.l, providing more general context beyond hunger. This basal ganglia extension allows for a positive feedback loop. which enables multiple rounds of voting, integrating values, such as with drift diffusion.

In the above, I’ve split the V.pt of the lamper into an ascending Vta (ventral tegmental area) dopamine area from mammals, but left the V.pt to represent the descending glutamate / GABA portion of Vta, despite mammals lacking a distinct V.pt. If there’s a food cue when hungry, H.l to Vta stimulation will generate high DA in S.v, enabling it, which will disinhibit V.pt to enable food seeing. Here, S.v / P.v is acting as the consensus circuit and the V.pt path is the action for food seeking.

As with the smaller Hb.l circuit, S.v / P.v is also part of a sleep / wake circuit using dopamine as a wake signal, as used in essay 29. If the animal is currently seeking food, it shouldn’t fall asleep, and the high dopamine signals to stay away. Again, from a narrative sense, this circuit could have been repurposed from a wake circuit, as opposed to a path conflict system.

In zebrafish Hb.l only projects to V.mr and does not project to any DA [Amo et al 2014], while in the more primitive lamprey Hb.l projects to both V.mr and DA [Stephensen-Jones et al 2011], which suggests that the V.mr projection is more functionally critical to this circuit than the Vta projection, or that the Vta circuit is a later development. The zebrafish V.pt has descending dopamine but the existence of significant projections to the striatum is questioned [Yamamoto and Vernier 2011].

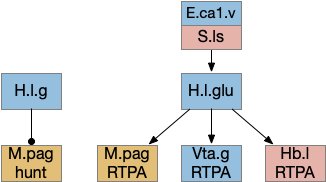

Note that H.l retains its central role, where the S.v circuit generalizes the base H.l function without replacing it. Stimulating H.l.g (H.l GABA neurons) can trigger seeking through its projection to Vta [Nieh et al 2016], and stimulating H.l.glu (glutamate H.l neurons) can trigger place avoidance through the H.l.glu projection to Hb.l [Stamatakis et al 2016].

Hippocampus digression

For place preference and place avoidance E.hc (hippocampus) plays a natural because E.hc represents context and place such as place cells, and H.hc projection strongly to both the hypothalamus and S.v. If we add the H.hc projections to H.l via S.ls, the seek / avoidance circuit looks something like the following.

H.l has neurons that represent food zones and non-food zones [Jennings et al 2015], presumably using E.hc place information, although possibly using P.bst (bed nucleus of the stria terminals) as an intermediary.

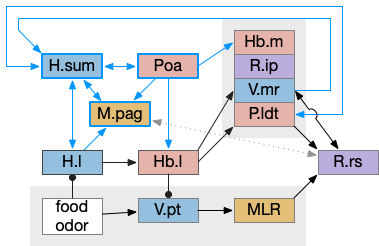

H.sum completing consensus loop

The consensus circuits needs to return the final action and motor choice back into the early layers, otherwise the motivation circuit wouldn’t know if a lower-level startle or OT looming escape took priority of the seek path. With analogy to the ascidian larva, this role resembles the AMG (ascending motor ganglia) neurons, which I associated with P.ldt and V.mr. For this consensus narrative, I’m taking H.sum (supramammillary) as the primary feedback node with an assist from Poa (preoptic area) to complete the loop to Hb.m and M.pag (periaqueductal gray).

H.sum has several sub circuits with different functions, which studies are only starting to untangle. H.sum tac1 (neurotransmitter aka substance P) is strongly associated with upcoming locomotion [Farrell et al 2021]. H.sum’s Poa projection is specifically associated with threat avoidant locomotion [Escobedo et al 2023].

V.mr and P.ldt are connected with R.rs and the bilateral OT circuit, and therefore have information about the selected action at the level of the hindbrain and motor afferent copies. Both are strongly connected to H.sum. H.sum also connects with M.pag (periaqueductal gray) and H.sum activates when M.pag.d is stimulated [Pan et al 2004]. H.sum also activates when the H.vm (ventromedial hypothalamus) threat nuclei are stimulated.

H.sum is immediately rostral to Vta and highly connected with it (not shown in the diagram.) H.sum contains some DA neurons itself, which are sometimes considered as an extension of A10, the Vta dopamine neuron area, although the neuron types differ [Yetnikoff et al 2014], [Menegas et al 2015].

H.sum is strongly connected with E.hc (hippocampus) and is one of the few external input to both E.dg (dentate gyrus) and E.ca2 (cornu ammonia), and is a major theta source to P.ms (medial septum), which drives E.hc theta. Its link to E.hc are important for both novel object exploration [Chen et al 2020], [Takahashi et al 2023] and social memory [Qin et al 2022]. Although I’m not yet adding E.hc to the essays, the novel object detection will be important soon to avoid repeated exploration of the same object.

Note that Poa has already participated in the Hb.m to R.ip circuit because Poa drives thermotaxis [Palieri et al 2024] as part of the original Hb aversive apical path.

M.pag tetrapod complications

In a sense, the vertebrate brain is designed around fish navigation, exemplified by the simple M-cell startle circuit that requires only three neurons between the acoustic sense and the swimming muscles. Although the direct Braitenberg-like connections to R.rs work for fish locomotion, tetrapod locomotion is more complex. M.pag (periaqueductal grey) is a central grey area surrounding the midbrain ventricle (“periaqueductal”), and it an inner ring to OT, which is immediately dorsal to it. Naming it “OT.dd” (deep, deep layer of OT) would not be unreasonable. Among other tasks like vocalization [Jürgens 1994] and hunting [Marín-Blasco et al 2020], M.pag provides a similar to R.rs but at a higher level, like syllables to phonemes. So in the following examples, M.pag can be viewed as similar functionality to R.rs.

Unlike R.rs, M.pag can access more sophisticated navigation. Where the M-cell can only turn left or right, M.pag can use OT for obstacle avoidance and even higher navigation of the hippocampus using H.pm.d (dorsal premammillary nucleus) [Wang et al 2021].

M.pag flight

M.pag implements innate behaviors, including flight, freezing, hunting, grooming, and vocalizations. The following diagram shows some of the looming flight circuitry [Zhou et al 2019]. As before, OT.m primarily processes the looming signal and OT.m sends input to M.pag.d as an integrated threat signal, where M.pag.d computes a threshold for responding to the threat [Evans et al 2018].

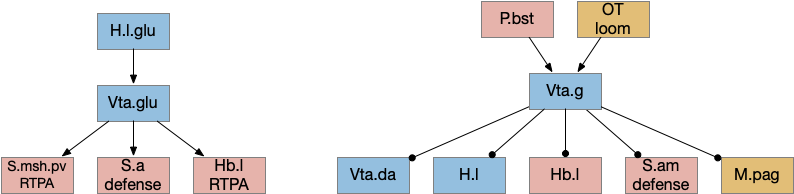

In the diagram, the second interesting path is through Vta.g (Vta GABA neurons) and S.a (central amygdala). Because OT.m and M.pag.d directly output to R.rs neurons, the projects to Vta.g and S.a aren’t required for motor control, but because of the distributed consensus system, other systems need to be informed of the looming response. S.a modulates defense, hunting, and eating systems, and Vta.g also inhibits the current action by suppressing dopamine, back to the consensus loop, suppressing any current seek action.

M.pag.vl avoidance

While M.pag.d is strongly associated with fast escape, M.pag.vl is more complicated with diverse functions including hunting [Franklin 2019], [Marín-Blasco et al 2020], vocalization [González-García et al 2024], and laughter [Klingbeil et al 2021]. Since this essay focuses on avoidance, where avoidance here isn’t the high speed predator escape of M.pag.d.

H.l lateral hypothalamus

As discussed above, H.l is a central motivational node, filling a similar role to the central hunger node in the mollusk sea hare navigation. However, H.l is much more complicated than a simple hunger node. One developmental paper divided H.l into nine distinct regions [Diaz et al 2013], but that anatomical division understates the complexity. A genetic transcription analysis finds 15 glutamate and 15 GABA clusters [Mickelson et al 2019]. Interestingly, the Diaz study identifies their H.l.1 area with H.sum.l, treating H.sum.l as part of H.l.

In general, H.l.glu produces place avoidance and H.l.g enables seeking, but as mentioned above with at least 15 genetic types and 9 regions, this division is almost certainly an oversimplification.

The H.l.glu to M.pag connection is certainly capable of driving motor avoidance. Interestingly, a different H.l population is part of the M.pag hunting circuit. Both Vta.g and Hb.l enter the motivation loop. I’ve added the E.ca1.v (ventral hippocampus CA1) input to H.l because E.hc.v (ventral hippocampus) is strongly associated with place, and E.hc.v specifically with aversive context.

R.pb peribrachial nucleus

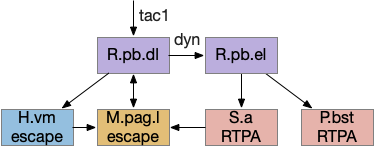

R.pb (peribrachial nucleus) is a pain, alarm, feeding, and respiration hub in the prepontine isthmus area (r0-r1). As an alarm center [Campos et al 2018], R.pb is connected with escaping and avoiding circuits. As covered in essay 29 speed, it includes a high Co2 trigger that drives place avoidance. It also includes pain triggers for escape. R.pb has multiple functions defined more by chemical markers than topology. One study explored R.pb’s role in escape and avoidance behavior [Chiang et al 2020].

R.pb.dl (dorsolateral R.pb) and R.pb.el are adjacent R.pb areas that are associated with alarm and pain responses. R.pb.dl receives direct N5 (trigeminal – head, jaw) and N.sp (spinal) pain input, including pain input marked by tac1 (tachykinin 1 peptide aka substance P). Relevant to this essay, the outputs divide between direct escape behavior with not learning and indirect avoidance behavior with learning. The M.pag.l projection produces flight and jumping. The S.a (central amygdala) and P.bst (bed nucleus of the stria terminalis – extended amygdala) projections produce real-time place avoidance and are capable of CPA (conditioned place avoidance) [Chiang et al 2020]. The R.pb example is useful because it combines a direct locomotion to M.pag with output to the slower consensus circuit.

Preoptic area

Poa (preoptic area) is a multifunctional area directly anterior to the hypothalamus and often considered part of the hypothalamus, although genetic markers suggest it’s more closely related to the forebrain. Like other brainstem areas, its functionality is more organized by genetic markers than topology.

The above diagram shows some of the Pom (medial preoptic area)functions. Temperature management has been discussed with a connection through Hb.m gradient following. Threat avoidance from signals from H.sum, H.pv (periventricular hypothalamus), or S.ls (lateral septum) can lead to RTPA through a M.pag projection [Escobedo et al 2023]. Local exploration, a RTPP function, also uses a M.pag projection [Shin et al 2023], and Pom can also enable hunting [Park et al 2018], although through a M.pag projection. The recent genetic research tools will likely unravel more of its functionality.

Poa has a strong projection to both Hb.m and Hb.l, suggesting that it’s an important node in the locomotion consensus circuit. In the thought experiment I’ve outlined above, Poa is part of the feedback system through H.sum, but Poa also receives E.hc.v (ventral hippocampus) input through S.ls (lateral septum), so it may be an important node in its own right.

Ppt / P.ldt

The ACh (acetylcholine) neurons near the midbrain-hindbrain boundary Ppt (pedunculopontine tegmentum) and P.ldt (laterodorsal tegmentum) are the core of the MLR. In simpler vertebrates like the lamprey, the MLR is only a single area, generally named P.ldt. In mammals, not only are P.ldt and Ppt split, but a chunk of locomotive action is in a different nucleus M.cnf (cuneiform). Although M.cnf is more of a direct locomotive area, the locomotive neurons don’t respect the anatomical boundary, but are a group of glutamate neurons spanning from Ppt to M.ncf, where Ppt and M.cnf are neighbors [Caggiano et al 2018]. Tetrapod locomotion is more complex than fish swimming, which may be a partial reason for the expansion and division.

Ppt is strongly reciprocally connected with the deeper layers of OT: OT.i for turning and sensory integration, and OT.d for seek and avoid. Its connections resemble the R.pgb (parabigeminal aka nucleus isthmi) which sustains attention for the OT.s (superficial OT) [Knudsen 2011] and covered in essay 19. R.pgb, Ppt, and P.ldt are sibling nuclei that develop from the same area in r1 that also produces R.pb and cerebellum granule cells [Pose-Méndez et al 2023].

P.ldt is complicated by the relative lack of recent studies of its descending projections since [Cornwall 1990] and an over-focus on its Vta connection. Because neuron tracing in [Zhao et al 2023] suggests that P.ldt has more descending connections to R.rs than Ppt and that all Vta connections are collaterals of R.rs connections, studies like [Coimbra et al 2021] and [Liu et al 2022] that find locomotion through Vta projections could be produced by its R.rs projection. P.ldt has reciprocal connections with H.sum.

Vta

Although Vta (ventral tegmental area) is most studied for its ascending dopamine projections to S.v (ventral stratum) and F.pfc (prefrontal cortex), it also contains glutamate and GABA projections, including descending connections. Non-tetrapods like fish and lamprey have a homologous V.pt (posterior tuberculum) with prominent descending locomotor connections to MLR [Ryczko et al 2017], [Derjean et al 2010]. The earlier thought experiment for the development of a locomotor consensus split out an ancient V.pt from the mammalian Vta as a way of describing the old descending functionality.

The above diagram shows some of the connections of the glutamate and GABA Vta [Taylor et al 2014], including projections to M.pag and to Hb.l that are direct locomotor for seek and avoid. The Vta is a main dopamine source for S.v and F.pfc with multiple distinct areas. Vta.m, which projects to S.msh (medial shell of S.v) is aversive, while Vta.l, which projects to S.lsh (lateral shell of S.v) and S.core (core of S.v) promotes seek [Szőnyi et al 2019]. Vta.m is non-reinforcing, as opposed to Vta.l, which is well-studied for reinforcement.

P.v ventral pallidum

P.v is a main output of S.v and the only output of S.ot (olfactory tubercle). As essay 29 covered, it’s an important sleep/wake node. For this essay, the important bit is a split between RTPP and RTPA depending on its output.

Links

References

Ables JL, Park K, Ibañez-Tallon I. Understanding the habenula: A major node in circuits regulating emotion and motivation. Pharmacol Res. 2023 Apr;190:106734.

Anselmi C, Fuller GK, Stolfi A, Groves AK, Manni L. Sensory cells in tunicates: insights into mechanoreceptor evolution. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024 Mar 14;12:1359207.

Basso MA, Bickford ME, Cang J. Unraveling circuits of visual perception and cognition through the superior colliculus. Neuron. 2021 Mar 17;109(6):918-937.

Berg EM, Björnfors ER, Pallucchi I, Picton LD, El Manira A. Principles Governing Locomotion in Vertebrates: Lessons From Zebrafish. Front Neural Circuits. 2018 Sep 13;12:73.

Beretta CA, Dross N, Guiterrez-Triana JA, Ryu S, Carl M. Habenula circuit development: past, present, and future. Front Neurosci. 2012 Apr 23;6:51.

Bhattacharyya K, McLean DL, MacIver MA. Visual Threat Assessment and Reticulospinal Encoding of Calibrated Responses in Larval Zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2017 Sep 25;27(18):2751-2762.e6.

Boulos LJ, Ben Hamida S, Bailly J, Maitra M, Ehrlich AT, Gavériaux-Ruff C, Darcq E, Kieffer BL. Mu opioid receptors in the medial habenula contribute to naloxone aversion. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020 Jan;45(2):247-255.

Braitenberg, V. (1986). Vehicles: Experiments in synthetic psychology. MIT press.

Brocard F, Ryczko D, Fénelon K, Hatem R, Gonzales D, Auclair F, Dubuc R. The transformation of a unilateral locomotor command into a symmetrical bilateral activation in the brainstem. J Neurosci. 2010 Jan 13;30(2):523-33.

Caggiano V, Leiras R, Goñi-Erro H, Masini D, Bellardita C, Bouvier J, Caldeira V, Fisone G, Kiehn O. Midbrain circuits that set locomotor speed and gait selection. Nature. 2018 Jan 25;553(7689):455-460.

Calvigioni D, Fuzik J, Le Merre P, Slashcheva M, Jung F, Ortiz C, Lentini A, Csillag V, Graziano M, Nikolakopoulou I, Weglage M, Lazaridis I, Kim H, Lenzi I, Park H, Reinius B, Carlén M, Meletis K. Esr1+ hypothalamic-habenula neurons shape aversive states. Nat Neurosci. 2023 Jul;26(7):1245-1255.

Campos CA, Bowen AJ, Roman CW, Palmiter RD. Encoding of danger by parabrachial CGRP neurons. Nature. 2018 Mar 29;555(7698):617-622.

Chen S, He L, Huang AJY, Boehringer R, Robert V, Wintzer ME, Polygalov D, Weitemier AZ, Tao Y, Gu M, Middleton SJ, Namiki K, Hama H, Therreau L, Chevaleyre V, Hioki H, Miyawaki A, Piskorowski RA, McHugh TJ. A hypothalamic novelty signal modulates hippocampal memory. Nature. 2020 Oct;586(7828):270-274.

Chen WY, Peng XL, Deng QS, Chen MJ, Du JL, Zhang BB. Role of Olfactorily Responsive Neurons in the Right Dorsal Habenula-Ventral Interpeduncular Nucleus Pathway in Food-Seeking Behaviors of Larval Zebrafish. Neuroscience. 2019 Apr 15;404:259-267.

Chen X, Engert F. Navigational strategies underlying phototaxis in larval zebrafish. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014 Mar 25;8:39.

Cheng RK, Krishnan S, Lin Q, Kibat C, Jesuthasan S. Characterization of a thalamic nucleus mediating habenula responses to changes in ambient illumination. BMC Biol. 2017 Oct 31;15(1):104.

Chiang MC, Nguyen EK, Canto-Bustos M, Papale AE, Oswald AM, Ross SE. Divergent Neural Pathways Emanating from the Lateral Parabrachial Nucleus Mediate Distinct Components of the Pain Response. Neuron. 2020 Jun 17;106(6):927-939.e5.

Chou MY, Amo R, Kinoshita M, Cherng BW, Shimazaki H, Agetsuma M, Shiraki T, Aoki T, Takahoko M, Yamazaki M, Higashijima S, Okamoto H. Social conflict resolution regulated by two dorsal habenular subregions in zebrafish. Science. 2016 Apr 1;352(6281):87-90.

Coimbra B, Domingues AV, Soares-Cunha C, Correia R, Pinto L, Sousa N, Rodrigues AJ. Laterodorsal tegmentum-ventral tegmental area projections encode positive reinforcement signals. J Neurosci Res. 2021 Nov;99(11):3084-3100.

Coombs S, Bak-Coleman J, Montgomery J. Rheotaxis revisited: a multi-behavioral and multisensory perspective on how fish orient to flow. J Exp Biol. 2020 Dec 7;223(Pt 23):jeb223008.

Cornwall J, Cooper JD, Phillipson OT. Afferent and efferent connections of the laterodorsal tegmental nucleus in the rat. Brain Res Bull. 1990 Aug;25(2):271-84.

Cregg JM, Leiras R, Montalant A, Wanken P, Wickersham IR, Kiehn O. Brainstem neurons that command mammalian locomotor asymmetries. Nat Neurosci. 2020 Jun;23(6):730-740.

Deacon RM, Rawlins JN. T-maze alternation in the rodent. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(1):7-12.

Derjean D, Moussaddy A, Atallah E, St-Pierre M, Auclair F, Chang S, Ren X, Zielinski B, Dubuc R. A novel neural substrate for the transformation of olfactory inputs into motor output. PLoS Biol. 2010 Dec 21;8(12):e1000567.

Diaz C, de la Torre MM, Rubenstein JLR, Puelles L. Dorsoventral Arrangement of Lateral Hypothalamus Populations in the Mouse Hypothalamus: a Prosomeric Genoarchitectonic Analysis. Mol Neurobiol. 2023 Feb;60(2):687-731.

do Carmo Silva RX, Lima-Maximino MG, Maximino C. The aversive brain system of teleosts: Implications for neuroscience and biological psychiatry. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018 Dec;95:123-135.

Dreosti E, Vendrell Llopis N, Carl M, Yaksi E, Wilson SW. Left-right asymmetry is required for the habenulae to respond to both visual and olfactory stimuli. Curr Biol. 2014 Feb 17;24(4):440-5.

Edwards SB (1980). The deep cell layers of the superior colliculus: their reticular characteristics and structural organization. In The Reticular Formation Revisted, Hobson JA, and Brazier MAB, eds. (New York: Raven Press; ), pp. 193–209.

Escobedo Abraham, Holloway Salli-Ann, Votoupal Megan, Cone Aaron L, Skelton Hannah E, Legaria Alex A., Ndiokho Imeh, Floyd Tasheia, Kravitz Alexxai V., Bruchas Michael R., Norris Aaron J. (2023) Glutamatergic Supramammillary Nucleus Neurons Respond to Threatening Stressors and Promote Active Coping eLife 12:RP90972

Evans DA, Stempel AV, Vale R, Ruehle S, Lefler Y, Branco T. A synaptic threshold mechanism for computing escape decisions. Nature. 2018 Jun;558(7711):590-594.

Farrell JS, Lovett-Barron M, Klein PM, Sparks FT, Gschwind T, Ortiz AL, Ahanonu B, Bradbury S, Terada S, Oijala M, Hwaun E, Dudok B, Szabo G, Schnitzer MJ, Deisseroth K, Losonczy A, Soltesz I. Supramammillary regulation of locomotion and hippocampal activity. Science. 2021 Dec 17;374(6574):1492-1496.

Fotowat H, Engert F. Neural circuits underlying habituation of visually evoked escape behaviors in larval zebrafish. Elife. 2023 Mar 14;12:e82916.

Franklin TB. Recent Advancements Surrounding the Role of the Periaqueductal Gray in Predators and Prey. Front Behav Neurosci. 2019 May 10;13:60.

Gardon O, Faget L, Chu Sin Chung P, Matifas A, Massotte D, Kieffer BL. Expression of mu opioid receptor in dorsal diencephalic conduction system: new insights for the medial habenula. Neuroscience. 2014 Sep 26;277:595-609.

Gillette R, Brown JW. The Sea Slug, Pleurobranchaea californica: A Signpost Species in the Evolution of Complex Nervous Systems and Behavior. Integr Comp Biol. 2015 Dec;55(6):1058-69.

González-García M, Carrillo-Franco L, Morales-Luque C, Dawid-Milner MS, López-González MV. Central Autonomic Mechanisms Involved in the Control of Laryngeal Activity and Vocalization. Biology (Basel). 2024 Feb 13;13(2):118.

Gouveia FV, Ibrahim GM. Habenula as a Neural Substrate for Aggressive Behavior. Front Psychiatry. 2022 Feb 17;13:817302

Guan NN, Xu L, Zhang T, Huang CX, Wang Z, Dahlberg E, Wang H, Wang F, Pallucchi I, Hua Y, El Manira A, Song J. A specialized spinal circuit for command amplification and directionality during escape behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Oct 19;118(42):e2106785118.

Heap LAL, Vanwalleghem G, Thompson AW, Favre-Bulle IA, Scott EK. Luminance Changes Drive Directional Startle through a Thalamic Pathway. Neuron. 2018 Jul 25;99(2):293-301.e4.

Helmbrecht TO, Dal Maschio M, Donovan JC, Koutsouli S, Baier H. Topography of a Visuomotor Transformation. Neuron. 2018 Dec 19;100(6):1429-1445.e4.

Hengenius JB, Connor EG, Crimaldi JP, Urban NN, Ermentrout GB. Olfactory navigation in the real world: Simple local search strategies for turbulent environments. J Theor Biol. 2021 May 7;516:110607.

Hikosaka O. The habenula: from stress evasion to value-based decision-making. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010 Jul;11(7):503-13.

Hirayama K, Moroz LL, Hatcher NG, Gillette R. Neuromodulatory control of a goal-directed decision. PLoS One. 2014 Jul 21;9(7):e102240.

Holland, L. Z. (2016). Tunicates. Current Biology, 26(4), R146-R152.

Hoyer J, Kolar K, Athira A, van den Burgh M, Dondorp D, Liang Z, Chatzigeorgiou M. Polymodal sensory perception drives settlement and metamorphosis of Ciona larvae. Curr Biol. 2024 Mar 25;34(6):1168-1182.e7.

Izquierdo EJ, Beer RD. Connecting a connectome to behavior: an ensemble of neuroanatomical models of C. elegans klinotaxis. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9(2):e1002890.

Jamieson D, Roberts A. Responses of young Xenopus laevis tadpoles to light dimming: possible roles for the pineal eye. J Exp Biol. 2000 Jun;203(Pt 12):1857-67.

Jennings JH, Ung RL, Resendez SL, Stamatakis AM, Taylor JG, Huang J, Veleta K, Kantak PA, Aita M, Shilling-Scrivo K, Ramakrishnan C, Deisseroth K, Otte S, Stuber GD. Visualizing hypothalamic network dynamics for appetitive and consummatory behaviors. Cell. 2015 Jan 29;160(3):516-27.

Jetti SK, Vendrell-Llopis N, Yaksi E. Spontaneous activity governs olfactory representations in spatially organized habenular microcircuits. Curr Biol. 2014 Feb 17;24(4):434-9.

Jürgens U. The role of the periaqueductal grey in vocal behaviour. Behav Brain Res. 1994 Jun 30;62(2):107-17.

Kermen F, Franco LM, Wyatt C, Yaksi E. Neural circuits mediating olfactory-driven behavior in fish. Front Neural Circuits. 2013 Apr 11;7:62.

Kim LH, Sharma S, Sharples SA, Mayr KA, Kwok CHT, Whelan PJ. Integration of Descending Command Systems for the Generation of Context-Specific Locomotor Behaviors. Front Neurosci. 2017 Oct 18;11:581.

Knudsen EI. Control from below: the role of a midbrain network in spatial attention. Eur J Neurosci. 2011 Jun;33(11):1961-72.

Klingbeil, J., Wawrzyniak, M., Stockert, A., Brandt, M. L., Schneider, H. R., Metelmann, M., & Saur, D. (2021). Pathological laughter and crying: insights from lesion network-symptom-mapping. Brain, 144(10), 3264-3276.

Kohashi T, Nakata N, Oda Y. Effective sensory modality activating an escape triggering neuron switches during early development in zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2012 Apr 25;32(17):5810-20.

Koide T, Miyasaka N, Morimoto K, Asakawa K, Urasaki A, Kawakami K, Yoshihara Y. Olfactory neural circuitry for attraction to amino acids revealed by transposon-mediated gene trap approach in zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Jun 16;106(24):9884-9.

Kourakis MJ, Borba C, Zhang A, Newman-Smith E, Salas P, Manjunath B, Smith WC. Parallel visual circuitry in a basal chordate. Elife. 2019 Apr 18;8:e44753.

Lacalli, T., & Candiani, S. (2017). Locomotory control in amphioxus larvae: new insights from neurotransmitter data. EvoDevo, 8, 1-8.

Lacalli Thurston 2022 An evolutionary perspective on chordate brain organization and function: insights from amphioxus, and the problem of sentience Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B3772020052020200520

Lima LB, Bueno D, Leite F, Souza S, Gonçalves L, Furigo IC, Donato J Jr, Metzger M. Afferent and efferent connections of the interpeduncular nucleus with special reference to circuits involving the habenula and raphe nuclei. J Comp Neurol. 2017 Jul 1;525(10):2411-2442.

Liu C, Tose AJ, Verharen JPH, Zhu Y, Tang LW, de Jong JW, Du JX, Beier KT, Lammel S. An inhibitory brainstem input to dopamine neurons encodes nicotine aversion. Neuron. 2022 Sep 21;110(18):3018-3035.e7.

Liu X, Huang H, Snutch TP, Cao P, Wang L, Wang F. The Superior Colliculus: Cell Types, Connectivity, and Behavior. Neurosci Bull. 2022 Dec;38(12):1519-1540.

Mallatt, Jon, Vertebrate origins are informed by larval lampreys (ammocoetes): a response to Miyashita et al., 2021, Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, Volume 197, Issue 2, February 2023, Pages 287–321.

Marín-Blasco, I. J., José Rangel Jr, M., Baldo, M. V. C., Motta, S. C., & Canteras, N. S. (2020). The lateral periaqeductal gray and its role in controlling the opposite behavioral choices of predatory hunting and social defense. bioRxiv, 2020-09.

Marquart GD, Tabor KM, Bergeron SA, Briggman KL, Burgess HA. Prepontine non-giant neurons drive flexible escape behavior in zebrafish. PLoS Biol. 2019 Oct 15;17(10):e3000480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000480.

Mast, S. O. (1921). Reactions to light in the larvae of the ascidians, Amarocium constellatum and Amarocium pellucidum with special reference to their photic orientation. J. Exp. Zool. 34, 149-187.

Menegas W, Bergan JF, Ogawa SK, Isogai Y, Umadevi Venkataraju K, Osten P, Uchida N, Watabe-Uchida M. Dopamine neurons projecting to the posterior striatum form an anatomically distinct subclass. Elife. 2015 Aug 31;4:e10032.

Mickelsen LE, Bolisetty M, Chimileski BR, Fujita A, Beltrami EJ, Costanzo JT, Naparstek JR, Robson P, Jackson AC. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of the lateral hypothalamic area reveals molecularly distinct populations of inhibitory and excitatory neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2019 Apr;22(4):642-656.

Nieh EH, Vander Weele CM, Matthews GA, Presbrey KN, Wichmann R, Leppla CA, Izadmehr EM, Tye KM. Inhibitory Input from the Lateral Hypothalamus to the Ventral Tegmental Area Disinhibits Dopamine Neurons and Promotes Behavioral Activation. Neuron. 2016 Jun 15;90(6):1286-1298.

Okamoto H, Cherng BW, Nakajo H, Chou MY, Kinoshita M. Habenula as the experience-dependent controlling switchboard of behavior and attention in social conflict and learning. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2021 Jun;68:36-43. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2020.12.005. Epub 2021 Jan 6. PMID: 33421772.

Palieri V, Paoli E, Wu YK, Haesemeyer M, Grunwald Kadow IC, Portugues R. The preoptic area and dorsal habenula jointly support homeostatic navigation in larval zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2024 Feb 5;34(3):489-504.e7.

Pan WX, McNaughton N. The supramammillary area: its organization, functions and relationship to the hippocampus. Prog Neurobiol. 2004 Oct;74(3):127-66.

Park SG, Jeong YC, Kim DG, Lee MH, Shin A, Park G, Ryoo J, Hong J, Bae S, Kim CH, Lee PS, Kim D. Medial preoptic circuit induces hunting-like actions to target objects and prey. Nat Neurosci. 2018 Mar;21(3):364-372. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0072-x. Epub 2018 Jan 29.

Pose-Méndez S, Schramm P, Valishetti K, Köster RW. Development, circuitry, and function of the zebrafish cerebellum. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2023 Jul 25;80(8):227.

Pottin K, Hyacinthe C, Rétaux S. Conservation, development, and function of a cement gland-like structure in the fish Astyanax mexicanus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Oct 5;107(40):17256-61.

Qin H, Fu L, Jian T, Jin W, Liang M, Li J, Chen Q, Yang X, Du H, Liao X, Zhang K, Wang R, Liang S, Yao J, Hu B, Ren S, Zhang C, Wang Y, Hu Z, Jia H, Konnerth A, Chen X. REM sleep-active hypothalamic neurons may contribute to hippocampal social-memory consolidation. Neuron. 2022 Dec 7;110(23):4000-4014.e6.

Quina LA, Harris J, Zeng H, Turner EE. Specific connections of the interpeduncular subnuclei reveal distinct components of the habenulopeduncular pathway. J Comp Neurol. 2017 Aug 15;525(12):2632-2656.

Randel N, Jékely G. Phototaxis and the origin of visual eyes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2016 Jan 5;371(1685):20150042.

Rétaux S, Pottin K. A question of homology for chordate adhesive organs. Commun Integr Biol. 2011 Jan;4(1):75-7.

Roussigné M, Bianco IH, Wilson SW, Blader P. Nodal signalling imposes left-right asymmetry upon neurogenesis in the habenular nuclei. Development. 2009 May;136(9):1549-57.

Ryan K, Lu Z, Meinertzhagen IA. The CNS connectome of a tadpole larva of Ciona intestinalis (L.) highlights sidedness in the brain of a chordate sibling. Elife. 2016 Dec 6;5:e16962. doi: 10.7554/eLife.16962.

Ryczko D, Grätsch S, Schläger L, Keuyalian A, Boukhatem Z, Garcia C, Auclair F, Büschges A, Dubuc R. Nigral Glutamatergic Neurons Control the Speed of Locomotion. J Neurosci. 2017 Oct 4;37(40):9759-9770.

Salas P, Vinaithirthan V, Newman-Smith E, Kourakis MJ, Smith WC. Photoreceptor specialization and the visuomotor repertoire of the primitive chordate Ciona. J Exp Biol. 2018 Apr 11;221(Pt 7):jeb177972.

Shin A, Ryoo J, Shin K, Lee J, Bae S, Kim DG, Park SG, Kim D. Exploration driven by a medial preoptic circuit facilitates fear extinction in mice. Commun Biol. 2023 Jan 27;6(1):106.

Stamatakis AM, Van Swieten M, Basiri ML, Blair GA, Kantak P, Stuber GD. Lateral Hypothalamic Area Glutamatergic Neurons and Their Projections to the Lateral Habenula Regulate Feeding and Reward. J Neurosci. 2016 Jan 13;36(2):302-11.

Stephenson-Jones M, Floros O, Robertson B, Grillner S. Evolutionary conservation of the habenular nuclei and their circuitry controlling the dopamine and 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HT) systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Jan 17;109(3):E164-73.

Stolfi, A., & Brown, F. D. (2015). Tunicata. Evolutionary developmental biology of invertebrates 6: Deuterostomia, 135-204.

Szőnyi A, Zichó K, Barth AM, Gönczi RT, Schlingloff D, Török B, Sipos E, Major A, Bardóczi Z, Sos KE, Gulyás AI, Varga V, Zelena D, Freund TF, Nyiri G. Median raphe controls acquisition of negative experience in the mouse. Science. 2019 Nov 29;366(6469):eaay8746.

Takahashi J, Yamada D, Nagano W, Sano Y, Furuichi T, Saitoh A. Oxytocinergic projection from the hypothalamus to supramammillary nucleus drives recognition memory in mice. PLoS One. 2023 Nov 16;18(11):e0294113.

Taylor SR, Badurek S, Dileone RJ, Nashmi R, Minichiello L, Picciotto MR. GABAergic and glutamatergic efferents of the mouse ventral tegmental area. J Comp Neurol. 2014 Oct 1;522(14):3308-34.

Temizer I, Donovan JC, Baier H, Semmelhack JL. A Visual Pathway for Looming-Evoked Escape in Larval Zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2015 Jul 20;25(14):1823-34.

Tosches, Maria Antonietta, and Detlev Arendt. The bilaterian forebrain: an evolutionary chimaera. Current opinion in neurobiology 23.6 (2013): 1080-1089.

Wagle M, Zarei M, Lovett-Barron M, Poston KT, Xu J, Ramey V, Pollard KS, Prober DA, Schulkin J, Deisseroth K, Guo S. Brain-wide perception of the emotional valence of light is regulated by distinct hypothalamic neurons. Mol Psychiatry. 2022 Sep;27(9):3777-3793.

Wang W, Schuette PJ, La-Vu MQ, Torossian A, Tobias BC, Ceko M, Kragel PA, Reis FM, Ji S, Sehgal M, Maesta-Pereira S, Chakerian M, Silva AJ, Canteras NS, Wager T, Kao JC, Adhikari A. Dorsal premammillary projection to periaqueductal gray controls escape vigor from innate and conditioned threats. Elife. 2021 Sep 1;10:e69178.

Yamamoto K, Vernier P. The evolution of dopamine systems in chordates. Front Neuroanat. 2011 Mar 29;5:21.

Yetnikoff L, Lavezzi HN, Reichard RA, Zahm DS. An update on the connections of the ventral mesencephalic dopaminergic complex. Neuroscience. 2014 Dec 12;282:23-48.

Yoshizawa M, Jeffery WR. Shadow response in the blind cavefish Astyanax reveals conservation of a functional pineal eye. J Exp Biol. 2008 Feb;211(Pt 3):292-9.

Zega, G., Thorndyke, M. C., & Brown, E. R. (2006). Development of swimming behaviour in the larva of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Journal of experimental biology, 209(17), 3405-3412.

Zhang BB, Yao YY, Zhang HF, Kawakami K, Du JL. Left Habenula Mediates Light-Preference Behavior in Zebrafish via an Asymmetrical Visual Pathway. Neuron. 2017 Feb 22;93(4):914-928.e4.

Zhao P, Jiang T, Wang H, Jia X, Li A, Gong H, Li X. Upper brainstem cholinergic neurons project to ascending and descending circuits. BMC Biol. 2023 Jun 6;21(1):135.

Zhou Z, Liu X, Chen S, Zhang Z, Liu Y, Montardy Q, Tang Y, Wei P, Liu N, Li L, Song R, Lai J, He X, Chen C, Bi G, Feng G, Xu F, Wang L. A VTA GABAergic Neural Circuit Mediates Visually Evoked Innate Defensive Responses. Neuron. 2019 Aug 7;103(3):473-488.e6.

Zwaka H, McGinnis OJ, Pflitsch P, Prabha S, Mansinghka V, Engert F, Bolton AD. Visual object detection biases escape trajectories following acoustic startle in larval zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2022 Dec 5;32(23):5116-5125.e3.