In an earlier essay that covered tunicates, the tunicate larva has two distinction visual action paths, one for phototaxis and one for looming. The two paths use different photoreceptors. Phototaxis photoreceptors are directional with pigment cells blocking light from one direction, while dimming photoreceptors are unidirectional with no shadow from pigment cells.

Looming and dimming are signals of both predators above the animal that block light from the sky, and of obstacles, which also blocks out light from the sky as the animal nears the barrier. In this essay I’ll be focusing on obstacle avoidance using a similar simulation approach as [Zhao et al 2023]. In general, the sky is the brightest, the ground is also light, such as sand, and obstacles are darker. So, if the eye is next to a barrier the average light is dim, while if it’s far from the wall the light is bright because the sky above and the lighter ground below are unobstructed.

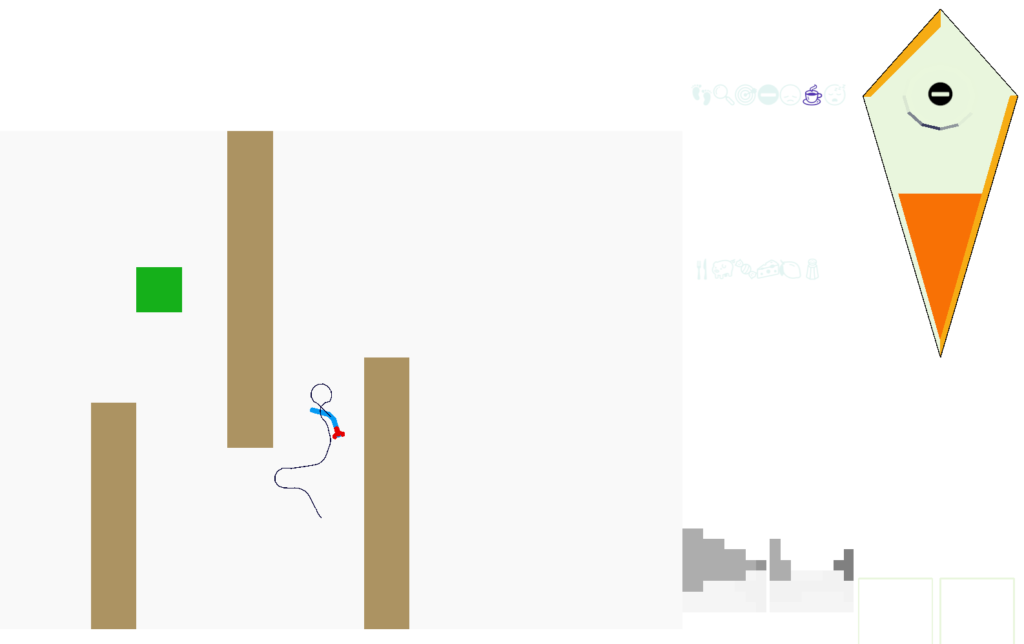

The above screenshot shows a fish-like create with a wall to its left. The left eye is next to a wall, and the right eye views the open field. If the image is reduced to a single average value, the left eye is dimmer, while the right is almost as bright as a full open field. As the first approaches the wall, the image dims rapidly.

Tunicate ascidian dimming

The tunicates (ascidian sea squirts) are the closest non-vertebrate chordates, although evolution has optimized them by removing features, making it difficult to draw direct comparisons to vertebrates [Holland 2016]. The ascidians have a simple larva form that swims for less than 24 hours before settling and becoming a sessile filter feeder.

The ascidian larva has a single ocellus (simple, non-image-forming photoreceptor area) has two distinct photoreceptor types and corresponding action paths, one that produces phototaxis and another that responds to rapid dimming [Ryan et al 2016].

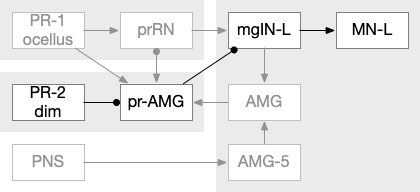

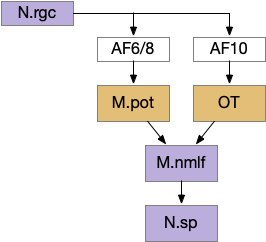

The above diagram of part of the ascidian larva nervous system, the PR-1 photoreceptors are directional for the top phototaxis path, while PR-2 non-directional photoreceptors produce dimming. The boxes above represent individual neurons, not larger functional groups. MgIN and MN are motor control and motor neurons [Ryan et al 2016].

Larval lamprey primitive eye

Lampreys and hagfish are the only remaining agnathans (non-jawed vertebrates), representing a much larger agnathan vertebrate group that preceded the jawed vertebrates, most of which were filter feeders or sediment feeders [Mallat 2023]. Lamprey larvae are unique among vertebrates in having a primitive non image-forming eye, more like the ascidian ocellus [Bayramov et al 2022]. The adult image-forming retina expands in rings around the more primitive center [Barandela et al 2023].

This central primitive eye is responsive to dimming, and it projects to an equivalent M.pot (pretectum), which handles several optical action paths in zebrafish, including dimming responses, phototaxis, OMR (optomotor reflexes), OKR (optokinetic reflex), and hunting.

Zebrafish retina arborization fields

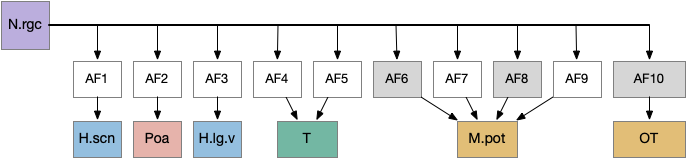

The zebrafish N.rgc (retina ganglion cell) projects to ten distinct AFs (arborization fields), each with a distinct purpose, from AF1 to H.scn (suprachiasmatic nucleus) for circadian timing to AF10 to OT (optic tectum) [Baier and Wullimann 2021]. In most cases distinct N.rgc neuron types project to distinct arborization fields. Even with the largest field AF10 for OT, individual N.rgc neurons project to distinct OT layers. The temporal phototaxis of a previous essay used the projection to AF4 to thalamus to Hb.m (medial habenula, dorsal Hb in zebrafish) [Cheng et al 2017], [Chen and Engert 2014].

The diagram above shows the zebrafish arborization fields and their targets, although the function of many of the targets is not fully known. Dimming fields include AF6, AF8 and OT [Baier and Wullimann 2021], [Temizier et al 2015]. It seems likely that AF6 and AF8 have distinct functionality, although the distinction is not yet known. In lamprey the central ocellus-like photoreceptors project to M.pot, while the outer, lateral image areas project to OT [Cornide-Petronio et al 2011]. The OT dimming response is directional, dimming in one side produces turning [do Carmo et al 2018].

Optic tectum

OT (optic tectum) has the largest arborization and it is the largest nucleus in the midbrain, larger than the entire zebrafish forebrain (cortex / basal ganglia). The optic tectum responds to looming objects and in zebrafish is used for visual hunting [Liu et al 2022]. Since the early vertebrates were filter feeders, the hunting functionality would be unnecessary, leaving obstacle and predator avoidance.

The optic tectum is layered with retina information arriving in the superficial layers, integrative information from other senses in intermediate layers, and motor actions from the intermediate and deep layers.

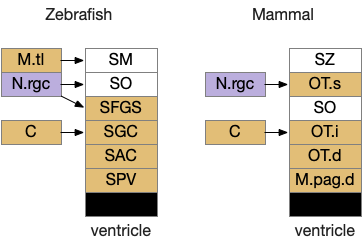

The above diagram shows a rough correspondence between zebrafish and mammal optic tectum layers. For simplicity, I’ll use the mammalian names. It’s not clear to me if the PV layer (periventricular layer) of zebrafish is equivalent to M.pag.d (dorsal periaqueductal grey), but I haven’t read any study addressing the physical similarity either as homologous or non-homologous, so it’s probably best to assume the location similarity is merely coincidental.

In zebrafish, the OT.s (superficial grey layer, SFGS in zebrafish) itself is layered with each layer receiving distinct N.rgc input [Liu et al 2022]. Dimming input goes to the deepest layer of OT.s [Temizier et al 2015], which is used by OT.d for looming responses [Heap et al 2018]. In mammals, OT.s receives retina input, OT.i produces turn actions, OT.d produces seek and avoid actions, and M.pag.dm produces fast escape from predators.

In vertebrates, OT uses visual expansion (looming) in combination with dimming [Nakagawa and Hongjian 2010], and dimming by itself does not trigger escape [Dunn et al 2016]. However, in the context of the essay’s simulation of a more primitive animal, expansion requires more sophisticated processing from an image-forming eye, which is only available for later vertebrates and not available to even the larval lamprey.

Torus longitudinus

In teleosts (most bony fish), M.tl (torus longitudinal) is a unique nucleus between the left and right OT. M.tl averages the dimming value between the right and left [Folgueira et al 2020]. It also has a sustain role, maintaining behavior after an initial signal.

Interestingly, M.tl is a CB-like (cerebellum-like) structure [Folgueira et al 2020]. Other CB-like ares such as MON (CB-like for LL) and DON (CB-like for electro sensation) act like adaptive filters for the lateral line to cancel out self-motion effects from sensors [Bell et al 2008], [Montgomery et al 2012].

Note that M.pot also communicates with its opposite side through the posterior commissure [Suzuki et al 2015], which could resemble an ancestral visual system. So, although M.tl is directly relevant to the looming response in zebrafish, it may be a specific teleost system, not an indication of an ancestral architecture.

nMLF optical motor output

The zebrafish reticulospinal motor control neurons are divided into several groups with distinct action paths. Optical motor output uses M.nmlf (nucleus of the medial longitudinal fasciculus), a midbrain reticulospinal group composed of 20 neurons on each side [Severi et al 2014]. M.nmlf avoidance is distinct from the Mauthner cell startle circuit in r4 in R.mrs. Although the OT looming / dimming can trigger the startle response [Temizer et al 2015], it generally uses the lower-priority M.nmlf [Bhattacharyya et al 2017].

This direct OT to M.nmlf projection applies to early zebrafish larva. As the fish ages, OT adds projections to R.mrs (middle reticulospinal) in r4-r6 of the hindbrain [Barandela et al 2023], including turning neurons marked by chx10 [Cregg et al 2020]. For this essay, I’m using the simpler early projection to M.nmlf.

Dimming information goes to AF6 and AF8, which are dendrites of M.pot [Heap et al 2018], which projects to M.nmlf [Portugues and Engert 2009].

Looming can produce zebrafish O-bends (u-turns) as well as directional turns [Portugues and Engert 2009], [Marques et al 2018]. For this essay, I’m assuming that M.pot produces a base O-bend command that the OT can modify by choosing a turn direction. This split between motivation and turning also occurs in R.mrs, where MLR (midbrain locomotive region) produces a non-directional forward movement, while chx10 neurons in R.mrs receive OT turning commands for looming [do Carmo et al 2018], [Cregg et al 2020].

Simulation

This essay’s simulation uses dimming as an obstacle avoidance system, similar to the simulation in [Zhao et al 2023], but with a minimal dimming input. The essay’s simulation condenses the input to the simplest dimming structure, where each eye has only a single averaged luminance value. The retina also calculates a dimming value as the difference between the current luminance and the previous value. Although the vertebrate retina uses distinct unsigned ON and OFF channels, the simulation uses a single signed value.

The looming module triggers a looming response when the dimming value passes a threshold as a proportion of the current luminance. This part of the model represents M.pot (pretectum). If no further information is available, the looming triggers a u-turn (O-bend in zebrafish) using M.nmlf.

If the left and right eyes have a difference in brightness, the model converts the u-turn into a left turn or right turn. This part of the model represents the OT’s dimming response. Like the M.pot output, this OT turn signal uses M.nmlf, as in the early zebrafish larva.

The above screenshot shows the animal avoiding an obstacle to its left. The two low-resolution images at the lower right are for human viewing and are higher resolution than the animal uses. The animal itself only uses a single averaged value for each eye. This view from the left eye is dominated by the wall, which blocks the light. The right eye mostly sees a clear view to the horizon.

Discussion

Qualitatively, the system works surprisingly well despite its simplicity. In some of the narrow corridors the u-turn behavior will reverse out of the corridor, and the entrance to the corridors is something of a barrier because only the center of the corridor will avoid triggering avoidance.

The model doesn’t adjust speed, which is an interesting potential improvement. If the animal slowed near obstacles, raised the threshold for obstacle avoidance, and reduced the turn angles, it might more easily navigate corridors. Since searching already has a roam vs dwell mode for ARS (area restricted search), triggered by serotonin, a slow-moving obstacle avoidance mode could use the same mechanism. V.dr (dorsal raphe serotonin) does reduce looming defense [Huang et al 2017]. Alternatively, since OT.d looming does habituate [Lee et al 2020], that habituation could reduce the excessive u-turning of the model. H.lgn.v (ventral lateral geniculate nucleus), which responds to overall light levels, can also inhibit the looming response [Fratzl et al 2021].

References

Baier H, Wullimann MF. Anatomy and function of retinorecipient arborization fields in zebrafish. J Comp Neurol. 2021 Oct;529(15):3454-3476.

Barandela M, Núñez-González C, Suzuki DG, Jiménez-López C, Pombal MA, Pérez-Fernández J. Unravelling the functional development of vertebrate pathways controlling gaze. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023 Oct 26;11:1298486.

Bayramov, A. V., Ermakova, G. V., Kucheryavyy, A. V., Meintser, I. V., & Zaraisky, A. G. (2022). Lamprey as laboratory model for study of molecular bases of ontogenesis and evolutionary history of vertebrata. Journal of Ichthyology, 62(7), 1213-1229.

Bhattacharyya K, McLean DL, MacIver MA. Visual Threat Assessment and Reticulospinal Encoding of Calibrated Responses in Larval Zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2017 Sep 25;27(18):2751-2762.e6.

Bell, Curtis C., Victor Han, and Nathaniel B. Sawtell. Cerebellum-like structures and their implications for cerebellar function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 31 (2008): 1-24.

Chen X, Engert F. Navigational strategies underlying phototaxis in larval zebrafish. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014 Mar 25;8:39.

Cheng RK, Krishnan S, Lin Q, Kibat C, Jesuthasan S. Characterization of a thalamic nucleus mediating habenula responses to changes in ambient illumination. BMC Biol. 2017 Oct 31;15(1):104.

Cornide-Petronio ME, Barreiro-Iglesias A, Anadón R, Rodicio MC. Retinotopy of visual projections to the optic tectum and pretectum in larval sea lamprey. Exp Eye Res. 2011 Apr;92(4):274-81.

Cregg JM, Leiras R, Montalant A, Wanken P, Wickersham IR, Kiehn O. Brainstem neurons that command mammalian locomotor asymmetries. Nat Neurosci. 2020 Jun;23(6):730-740.

do Carmo Silva RX, Lima-Maximino MG, Maximino C. The aversive brain system of teleosts: Implications for neuroscience and biological psychiatry. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018 Dec;95:123-135.

Dunn TW, Gebhardt C, Naumann EA, Riegler C, Ahrens MB, Engert F, Del Bene F. Neural Circuits Underlying Visually Evoked Escapes in Larval Zebrafish. Neuron. 2016 Feb 3;89(3):613-28.

Folgueira M, Riva-Mendoza S, Ferreño-Galmán N, Castro A, Bianco IH, Anadón R, Yáñez J. Anatomy and Connectivity of the Torus Longitudinalis of the Adult Zebrafish. Front Neural Circuits. 2020 Mar 13;14:8.

Fratzl A, Koltchev AM, Vissers N, Tan YL, Marques-Smith A, Stempel AV, Branco T, Hofer SB. Flexible inhibitory control of visually evoked defensive behavior by the ventral lateral geniculate nucleus. Neuron. 2021 Dec 1;109(23):3810-3822.e9.

Heap LAL, Vanwalleghem G, Thompson AW, Favre-Bulle IA, Scott EK. Luminance Changes Drive Directional Startle through a Thalamic Pathway. Neuron. 2018 Jul 25;99(2):293-301.e4.

Holland, L. Z. (2016). Tunicates. Current Biology, 26(4), R146-R152.

Huang L, Yuan T, Tan M, Xi Y, Hu Y, Tao Q, Zhao Z, Zheng J, Han Y, Xu F, Luo M, Sollars PJ, Pu M, Pickard GE, So KF, Ren C. A retinoraphe projection regulates serotonergic activity and looming-evoked defensive behaviour. Nat Commun. 2017 Mar 31;8:14908.

Lee KH, Tran A, Turan Z, Meister M. The sifting of visual information in the superior colliculus. Elife. 2020 Apr 14;9:e50678.

Liu X, Huang H, Snutch TP, Cao P, Wang L, Wang F. The Superior Colliculus: Cell Types, Connectivity, and Behavior. Neurosci Bull. 2022 Dec;38(12):1519-1540.

Mallatt, Jon, Vertebrate origins are informed by larval lampreys (ammocoetes): a response to Miyashita et al., 2021, Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, Volume 197, Issue 2, February 2023, Pages 287–321.

Marques, João C., et al. Structure of the zebrafish locomotor repertoire revealed with unsupervised behavioral clustering. Current Biology 28.2 (2018): 181-195.

Montgomery, John C., David Bodznick, and Kara E. Yopak. The cerebellum and cerebellum-like structures of cartilaginous fishes. Brain Behavior and Evolution 80.2 (2012): 152-165.

Nakagawa H, Hongjian K. Collision-sensitive neurons in the optic tectum of the bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana. J Neurophysiol. 2010 Nov;104(5):2487-99.

Portugues R, Engert F. The neural basis of visual behaviors in the larval zebrafish. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009 Dec;19(6):644-7.

Ryan K, Lu Z, Meinertzhagen IA. The CNS connectome of a tadpole larva of Ciona intestinalis (L.) highlights sidedness in the brain of a chordate sibling. Elife. 2016 Dec 6;5:e16962.

Severi KE, Portugues R, Marques JC, O’Malley DM, Orger MB, Engert F. Neural control and modulation of swimming speed in the larval zebrafish. Neuron. 2014 Aug 6;83(3):692-707.

Suzuki, D. G., Murakami, Y., Escriva, H., & Wada, H. (2015). A comparative examination of neural circuit and brain patterning between the lamprey and amphioxus reveals the evolutionary origin of the vertebrate visual center. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 523(2), 251-261.

Temizer I, Donovan JC, Baier H, Semmelhack JL. A Visual Pathway for Looming-Evoked Escape in Larval Zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2015 Jul 20;25(14):1823-34.

Zhao J, Xi S, Li Y, Guo A, Wu Z. A fly inspired solution to looming detection for collision avoidance. iScience. 2023 Mar 5;26(4):106337.