[Arendt 2015] examines the fundamental divisions of the nervous system by looking at ancestral cell divisions in some of the earliest animals, specifically a multicellular amoeboid bottom-feeder that glides on a mucus foot like a slug. The archaoslug moves like an amoeba instead of a true slug because it’s body isn’t symmetrical bilateral: there’s no front or side. The Adrent study is interesting for the essays because it fundamentally splits chemosensory control (hypothalamic and olfactory) split from mechanosensory / optosensory sense and muscle brain at the cell type and developmental level.

In this proto-slug, cells have specialized into three major classes:

- External skin with mechanosensory and optosensory cells

- Internal digestive gut

- Mucociliary sole with chemosensory and locomotion cells

The mucociliary sole moves with cilia gliding over mucus. Chemical sensors that detect food choose when to stop. A similar locomotive strategy is described in [Smith 2015] and [Senatore 2017] for the existing algae-grazing, disc-shaped animal Trichoplax, which lacks any nerves at all and only has six cells in total [Smith 2014].

Locomotion and food searching for the archaoslug is simple: stop when the chemosensors detects food (algae), and move in a random brownian direction when no food is available. A simple chemical sensor and a peptide-based broadcast system would suffice, as in Trichoplax. Because the bacterial mats may have dominated the Precambrian environment, the brownian motion pausing for food could work.

The ventral skin specialized into mechanosensory cells, optosensory cells, and contractile cells which developed into the first neurons and muscles. The animal can avoid obstacles and threats using nerve nets that broadcast and repeat signals, like the repeating nerve nets in cnidaria (jellyfish, sea anemone, and corals) [Seipel 2005]. Note, though, the control circuits for between locomotion (mucociliary sole) and muscles (skin/body contractions) are distinct, and don’t even coordinate. A sea anemone or a slug will contract when touched, but the sea anemone has no locomotion and the slug’s contraction isn’t its primary locomotion. Similarly, an archeoslug with primitive muscles might only use the muscles to avoid obstacles, contracting when it runs into something, but its primary motion remains the ciliary, non-muscular sole. Meaning, the locomotive drive (arrest, approach, avoid) is controlled independently from navigation (spatial obstacle avoidance.)

This division into three types influences all later cell development, because the initial decisions shape the later evolved cell types. Genetic signaling to choose between the three might have created a path dependent split between three types.

Discussion

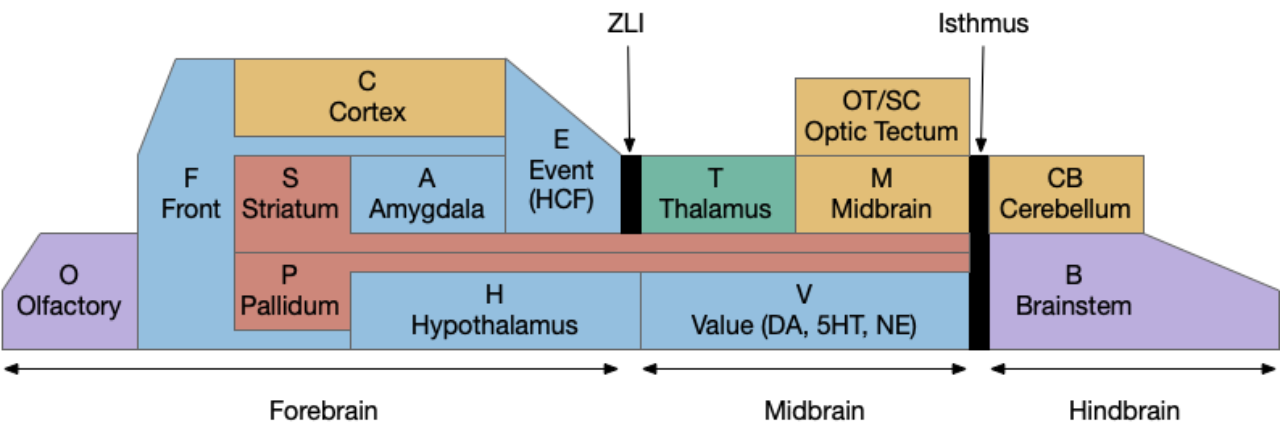

This split between chemosensory sole and mechano- and opto-sensory skin and muscle obviously mirrors the vertebrate split between the limbic system (olfactory and hypothalamic) and optic tectum system, but with a different spin. The limbic system is generally described as a motivational and emotional center. The root word for both motivation and emotion is the Latin movere, to move, which has less baggage than either word. The mucociliary sole area does move and control movement, but it’s hardly an emotional center. But the mucociliary sole area isn’t unique in its control of motion, because the unrelated skin/muscle area controls navigation.

Treating the mind as independent, conflicting centers resembles Dawkins’ descriptions of genes in The Selfish Gene, where each gene works independently and in competition with others, and coordination only occurs for mutual benefit. The general idea of competing mental centers is also in Minsky’s Society of mind, and the idea is older than either. So, the value of the archaeoslug isn’t the general idea of a divided mind, but the specific division that occurred in evolution.

References

Arendt D, Benito-Gutierrez E, Brunet T, Marlow H. Gastric pouches and the mucociliary sole: setting the stage for nervous system evolution. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015 Dec 19;370(1684):20150286. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0286. PMID: 26554050; PMCID: PMC4650134.

Dawkins, Richard. The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press, 2006.

Minsky, Marvin. Society of mind. Simon and Schuster, 1988.

Senatore A, Reese TS, Smith CL. Neuropeptidergic integration of behavior in Trichoplax adhaerens, an animal without synapses. J Exp Biol. 2017 Sep 15;220(Pt 18):3381-3390. doi: 10.1242/jeb.162396. PMID: 28931721; PMCID: PMC5612019

Smith CL, Pivovarova N, Reese TS. Coordinated Feeding Behavior in Trichoplax, an Animal without Synapses. PLoS One. 2015 Sep 2;10(9):e0136098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136098. PMID: 26333190; PMCID: PMC4558020.

Smith CL, Varoqueaux F, Kittelmann M, Azzam RN, Cooper B, Winters CA, Eitel M, Fasshauer D, Reese TS. Novel cell types, neurosecretory cells, and body plan of the early-diverging metazoan Trichoplax adhaerens. Curr Biol. 2014 Jul 21;24(14):1565-1572. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.05.046. Epub 2014 Jun 19. PMID: 24954051; PMCID: PMC4128346.