I like the model of motivation where the hypothalamus and midbrain structures like the ventral tegmental area (Vta), periaqueductal gray (M.pag), and parabrachial nucleus (B.pb) form the motivational core, primarily run by neuropeptides signaling, based on old chemical communication. [Damasio and Carvalho 2013] consider this area as an organized map for feelings, like the optic tectum (OT) has a retina-centric map for visual interest.

To avoid getting stuck in philosophical woo, I’m avoiding the question of whether this area is a primary source of feelings, but I like the idea of a semi-organized map at the base of motivation. The parabrachial nucleus (B.pb) is a good place to start, because its neurons encode warnings like pain, visceral summaries, and primitive feeding, including basic taste.

Parabrachial nucleus

B.pb provides a coarse summary of taste, pain, temperature, and visceral feelings like malaise without the details. It can report that something tastes good because it’s sweet or tastes bad because it’s bitter, but can’t experience chocolate. It’s more of an action-focused alarm [Campos et al. 2018] than a sensory experience.

For example, if B.pb detects bitter taste or malaise, it sends a general notice to other areas in the peptide core to stop eating and investigate further. If B.pb tastes sweet, it encourages eating. In addition to senses like taste and warning, B.pb has action control of its own, including reflexive escape actions, breathing and heart rate to the medulla (B.mdd) and B.nts. So, it can serve as a lower-level action hub.

B.pb and neuropeptides

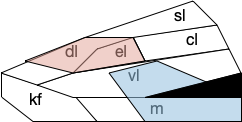

B.pb poses an immediately difficulty for the simulation animal because it’s organized chemically by neuropeptides instead of a simple topological and connectivity map. The following diagram is a broad topographic map of B.pb [Chiang et al. 2019] that illustrates the issue.

As shown above, the colored areas do not respect the named boundaries. The blue area represents taste neuron areas and the red area represents general alarm (pain, heat, cold, malaise, etc.) But even those colored areas are an oversimplification because neuron functions are mixed together salt-and-pepper style. [Pauli et al. 2022] found 21 subclusters of B.pb neuron peptide receptors and transmission, each of which may have distinct projection patterns.

This neuropeptide focus isn’t restricted to B.pb. The lateral hypothalamus (H.l), another major node in the feeding circuit, is also organized by neuropeptides, including important ones like orexin (exploring), and MCH, which it sends across the entire brain. Although [Diaz et al. 2023] has broken H.l into 9 areas, these may not be sufficient because of the neuropeptide focus. [Mickelsen et al. 2019] found 15 clusters of glutamate neurons and 15 clusters of GABA neurons. [Guillaumin and Burdakov 2017] and [Burdakov and Karnani 2020] find H.l functional communication through neuropeptides that are invisible to traditional synaptic communication.

Neuropeptide core

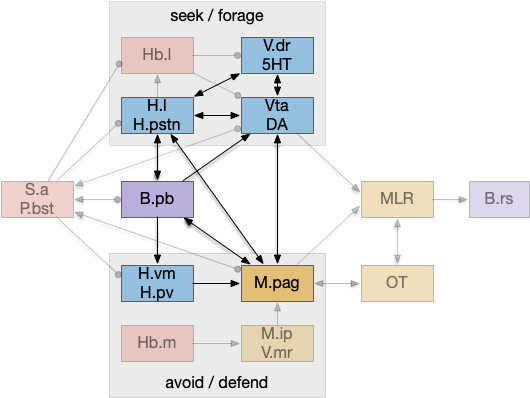

An “isodendritical core” [Ramón-Moliner and Nauta 1966] in the hypothalamus and midbrain is an old idea with a more modern description in [Agnati et al. 2010], which is a good starting point for the essay simulation. The core includes reticular areas of the hypothalamus, B.pb, M.pag, and the Vta (aka posterior tuberculum in zebrafish). “Neuropeptide core” matches my imagination of this area better than the old name. A diagram of the core is below, with the caveat that neuropeptide broadcasting is more important for communication than the diagram’s arrows.

As shown above, the neuropeptide core is highly interconnected. B.pb includes taste and visceral sensation like nausea together with visceral control. H.l includes blood sensors like glucose level, insulin, and fat and protein levels. M.pag includes many innate behaviors including freezing, flight and grooming. Vta controls actions, including seeking and searching.

As the diagram illustrates, the neural connectivity of the inner core is not particularly useful because they’re all entirely interconnected. For simplicity of the essay simulation, I’m using a model where the core neuropeptides are shared in a common neuropeptide soup, or canal, where the neuropeptide identity is more important than the neuron’s specific physical location. For example, treating B.pb as one or two areas instead of the seven areas above.

Cerebrospinal fluid as neuropeptide canal

The periventricular areas like H.pv and M.pag are named for their location around the ventricles, which contains cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). These areas contain neurons that directly sense neurotransmitters and neuropeptides in the CSF itself. The CSF can be a canal for transmitting neuropeptides [Bjorefeldt et al. 2018].

Earlier photo-vertebrate animals may have used a similar canal more extensively. Because of the smaller brain size, diffusion in the canal may have been sufficient for communication without point to point synapses. [Vigh et al. 2004] point out that amphioxus larva, a pre-vertebrate chordate, has much of its com munition in a single neuropile (intertwined dendrites and axons) that’s open to sea water until its neural tube closes as an adult.

Neuropeptides and timing

Neuropeptides act on a much slower timescale than faster neurotransmitters like glutamate and GABA. Glutamate and GABA synapse are a few microseconds and clear rapidly. Neuropeptides can persist tens of seconds to tens of minutes. For an animal’s motivation, like fleeing a predator, the longer timescale is more appropriate, because the animal shouldn’t stop fleeing if it loses sight of the predator for ten milliseconds or even a second or two. Similarly, foraging for food is a longer task measured in many minutes or hours, not milliseconds. The longer chemical timing of the peptides is more suited to motivational timing than the fast reactive transmitters.

Peptide circuits

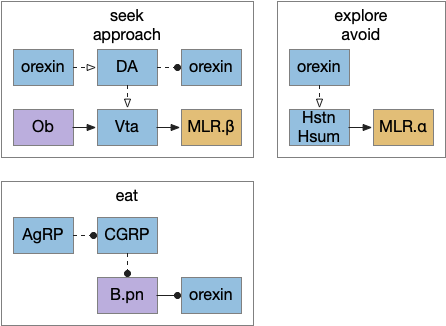

I’ve sketched out some possible neuropeptide circuits for feeding are portrayed in the diagram below, organized by behavior.

The first diagram shows dopamine as a primary seeking neurotransmitter [Alcaro et al. 2007]. When the animal finds target by odor in the simulation, dopamine tells the Vta to connect the olfactory bulb (Ob) to the motor locomotive region (MLR), aiming the animal to the food scent.

The second shows orexin as a general food exploration signal. In contrast with the target-focused seeking, exploration is a random search.

The third is part of the eating circuit, where CGRP (an alarm neuropeptide) tonically inhibits eating, until AgRP (a hunger neuropeptide) disinhibits it [Essner et al. 2017].

References

Agnati, L. F., Guidolin, D., Guescini, M., Genedani, S., & Fuxe, K. (2010). Understanding wiring and volume transmission. Brain research reviews, 64(1), 137-159.

Alcaro A, Brennan A, Conversi D. The SEEKING Drive and Its Fixation: A Neuro-Psycho-Evolutionary Approach to the Pathology of Addiction. Front Hum Neurosci. 2021 Aug 12;15:635932.

Bjorefeldt A, Illes S, Zetterberg H, Hanse E. Neuromodulation via the Cerebrospinal Fluid: Insights from Recent in Vitro Studies. Front Neural Circuits. 2018 Feb 5;12:5.

Burdakov D, Karnani MM. Ultra-sparse Connectivity within the Lateral Hypothalamus. Curr Biol. 2020 Oct 19;30(20):4063-4070.e2.

Campos CA, Bowen AJ, Roman CW, Palmiter RD. Encoding of danger by parabrachial CGRP neurons. Nature. 2018 Mar 29;555(7698):617-622.

Chiang, M. C., Bowen, A., Schier, L. A., Tupone, D., Uddin, O., & Heinricher, M. M. (2019). Parabrachial Complex: A Hub for Pain and Aversion. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 39(42), 8225-8230.

Damasio A, Carvalho GB. The nature of feelings: evolutionary and neurobiological origins. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013 Feb;14(2):143-52.

Diaz, C., de la Torre, M.M., Rubenstein, J.L.R. et al. Dorsoventral Arrangement of Lateral Hypothalamus Populations in the Mouse Hypothalamus: a Prosomeric Genoarchitectonic Analysis. Mol Neurobiol 60, 687–731 (2023).

Essner RA, Smith AG, Jamnik AA, Ryba AR, Trutner ZD, Carter ME. AgRP Neurons Can Increase Food Intake during Conditions of Appetite Suppression and Inhibit Anorexigenic Parabrachial Neurons. J Neurosci. 2017 Sep 6;37(36):8678-8687.

Guillaumin MCC, Burdakov D. Neuropeptides as Primary Mediators of Brain Circuit Connectivity. Front Neurosci. 2021 Mar 11;15:644313.

Mickelsen LE, Bolisetty M, Chimileski BR, Fujita A, Beltrami EJ, Costanzo JT, Naparstek JR, Robson P, Jackson AC. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of the lateral hypothalamic area reveals molecularly distinct populations of inhibitory and excitatory neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2019 Apr;22(4):642-656.

Pauli JL, Chen JY, Basiri ML, Park S, Carter ME, Sanz E, McKnight GS, Stuber GD, Palmiter RD. Molecular and anatomical characterization of parabrachial neurons and their axonal projections. Elife. 2022 Nov 1;11:e81868.

Pessoa L, Medina L, Desfilis E. Refocusing neuroscience: moving away from mental categories and towards complex behaviours. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2022 Feb 14;377(1844):20200534.

Ramón-Moliner E, Nauta WJ. The isodendritic core of the brain stem. J Comp Neurol. 1966 Mar;126(3):311-35.

Vígh B, Manzano e Silva MJ, Frank CL, Vincze C, Czirok SJ, Szabó A, Lukáts A, Szél A. The system of cerebrospinal fluid-contacting neurons. Its supposed role in the nonsynaptic signal transmission of the brain. Histol Histopathol. 2004 Apr;19(2):607-28.