Essay 27 returns to feeding, which essay 23 had an earlier sketch of. While the animal in earlier essays could eat while moving, like snails and worms, this essay will add the requirement of stopping before eating, which requires extra control mechanisms to manage the state transition.

A filter feeder like amphioxus, a non-vertebrate chordate that may hint at pre-vertebrate feeding, might move to find a better feeding zone, but then settles down as a static filter feeder. Tunicates, which are more closely related to vertebrates settle down permanently as adults and dissolve their brain as no longer needed. Because I want to keep the essay simple, I’m imaging something more like licking, which is more studied in rodents, as opposed to a more alien filter feeding. The main problem for the essay to introduce locomotion and eating as distinct actions.

As a contrast to further explore the idea of states and state transitions, the essays also explores the transition between roaming and dwelling: global wide-ranging search vs area restricted search. Roaming and dwelling are more amorphous motivational states as opposed to the strict motor division between moving and eating.

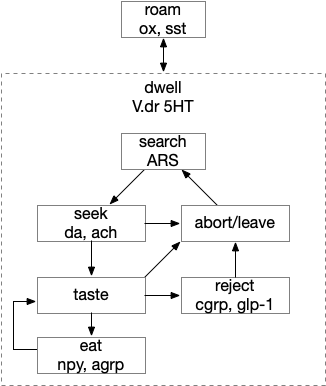

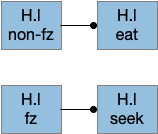

Feeding states

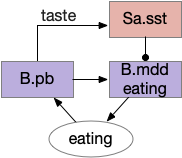

Below is a more detailed diagram of the foraging and feeding states, revolving around the core foraging task. The animal passively roams until is finds an odor cue for a food target, which starts a seek to the target. If it finds food, the animal sops and eats.

In this model, the roam state and dwell state can be separate from seeking a target, depending on the animal’s environmental niche. A seek can start in a roam state or a dwell state, and seek cues may or may not initiate dwell state. For example, dwell state might only start when the animal eats nutritious food, indicating that food is nearby.

The diagram includes important failure states. If seeking fails, the animal gives up and leaves the area, and must ignore the last cue to avoid perseveration. If the taste is bitter or toxic, the animal rejects the food. For now, I’m postponing longer failure states like the food lacking nutritional value or causing food poisoning.

To avoid perseveration, seeking the failed cue forever, the avoid state moves the animal away from the failed cue and ignores seek cues. A more sophisticated brain could remember the failed cue for a short time, but the current essays lack short term memory.

Eating here means specifically licking or filter feeding. I’m being precise here because the simulation requires it, and more vague neuroscience terms like “reward” are often unclear about exactly what it’s relation to actual eating are.

The connection between the dwell state and serotonin is from [Flavell et al 2013], [Ji et al 2021] which founds serotonin marking the dwell state in the flatworm C. elegans, and [Marques et al 2020] finding serotonin for a zebrafish dwell (“exploit”) state.

Roaming and dwelling

Food search phases have multiple strategies, broadly divided into roaming and dwelling. Roaming is a broader, more general search without a specific area or target. Dwelling or ARS (area restricted search) is slower, with tighter turning, where the current area is believed to be more likely to have food. [Horstick et al 2017] describes dwell as four properties: reduction in travel distance, increased change in orientation, increased path complexity, and a directional bias.

For this essay, dwelling is a motivational drive not a motor command, meaning it can overlap with other motivations and doesn’t provide a strict action state requirement. For example, dwell isn’t required to seek a target, which can occur in the roaming state, for example in C. elegans [Ji et al 2021].

In the C. elegans the dwell state is associated with serotonin and the roam state with PDF (pigment dispensing factor) [Flavell et al 2013]. In zebrafish the dwell state is associated with V.dr (dorsal raphe) serotonin [Marques et al 2020], the roam state is associated with SST (somatostatin peptide) [Horstick et al 2017]. While arousal isn’t quite the same as well, [Lovett-Barron et al 2017] found SST as a low-arousal marker, while CART, ACh (acetylcholine), NE (norepinephrine), serotonin, dopamine and NPY (neuropeptide Y) as signs of high arousal.

Triggers for the dwell state depend on the animal’s species [Dorfman et al 2020]. In C. elegans, which feeds on bacteria, nutritional feedback extends the dwell state [Ben Arous et al 2009]. In some animals a food cue triggers dwell, while in others only eating nutritious food triggers dwell. In zebrafish lack of a food cue causes H.c (caudal hypothalamus) activation decay [Wee et al 2019].

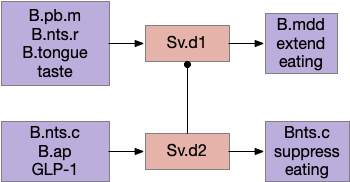

Reflexive eating

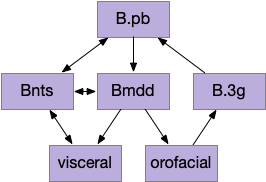

This essay models reflexive eating as a hindbrain system controlled by B.pb (parabrachial nucleus) with downstream motor and sensory in B.nts (nuclei tractus solitarius), M.mdd (reticular medulla), and B.3g (trigeminal – orofacial sensorimotor). The simulation isn’t as detailed, treating the hindbrain eating as a single low-level module.

This innate circuit can with without input from higher areas [Watts et al 2022]. For example if rodents lack any dopamine, they won’t move or eat and will starve even if food is near them. However, if food or water is placed at their lips, which activates the innate circuit, the rodents will eat [Rossi et al 2016].

The B.pb area also processes sweet, bitter or salt, and can reject food without requiring higher areas. The higher areas modulate B.pb behavior, such as suppressing B.pb’s innate rejection of sour when drinking lemonade.

Because the B.pb innate eating and the MLR (midbrain locomotor region) are independent, some system much coordinate switching between moving and eating.

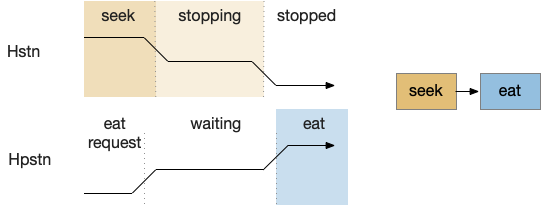

The illusion of state machine atomicity

The feeding state diagram suggests a simple atomic transition from seeking food to eating the food, but this transition needs management from some neural circuits. For example, when braking during driving, drivers need to pay attention to the stopping distance. Braking stops a car, but the state transition isn’t a simple atomic transition. For this essay’s eating task, some neural circuit must keep track of the animal’s stopping after seeking and only allow eating when locomotion has stopped.

H.stn (subthalamic nucleus) is involved with stopping, waiting, and switching tasks [Isoda and Hikosaka 2008]. Since H.stn also receives motor efference copies via T.pf (thalamus parafascicular nucleus) and Ppt (peduncular pontine nucleus), H.stn is in a good position to manage the stopping transition and can prevent eating until the locomotion has ended. The diagrams shows H.pstn (parasubthalamic nucleus) as a parallel area for gaiting eating, following [Barbier et al 2021].

H.stn and H.pstn state transition circuit

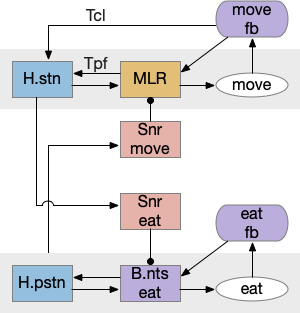

H.stn and H.pstn are well-placed to fulfill the transitions between seeking and eating. To flesh this idea out, here’s a simplified model of the seal to eat state transition circuit.

The main action paths are horizontal: moving is from H.stn to MLR to B.rs (reticulospinal motor neurons) and eating is from H.pstn to B.nts to orofacial licking motor neurons. The rest of the circuit manages the transition between the two states.

Control over the transition comes from S.nr (substantia nigra pars reticulata), which inhibits eating when the animal is moving, and inhibits moving while the animal is eating. To know when the animal has stopped moving, H.stn receives motor efferent copies from T.cl and T.pf (centrolateral and parafascicular thalamus, aka intralaminar). As a note, T.cl contains cerebellum output, so H.stn may receive fine-grained motor timing feedback. H.pstn receives parallel eating efferent copies from B.pb and B.nts to know when the animal has stopped eating.

This circuit has the same structure as a lateral inhibition decision circuit, but the function is about handling timing and transition, not deciding between competing options.

Note: [Shah et al 2022] suggest H.pstn is more specific to suppressing feeding for aversive situations like food poisoning or a predator threat, but not the motor control as described here.

A note on this model: the actual neural circuit isn’t as clean, parallel and logical, because evolution isn’t an intelligent designer. Furthermore, this brain region is part of the neuropeptide core, where neuropeptide broadcast-like signaling can be more important than point-to-point circuit diagrams. Specifically, the disinhibition of B.pb eating is more likely peptides from the hypothalamus, not S.nr tonic inhibition.

H.l food zone

Studies on H.l (lateral hypothalamus) show two interesting results relevant here [Jennings et al 2015]:

- Two distinct GABA neuron populations gate eating and seeking.

- Two distinct neuron populations are active in a food zone or outside a food zone.

The food zone neurons partially explain how H.l decides between seeking and eating. How does this animal knows when it’s reached the food? In C. elegans there are dopamine chemosensory neurons that sense when the animal passes over food bacteria, and signals the animal to slow [Sawin et al 2000]. Dopamine chemosensory neurons also signal for the animal to turn more when leaving food (dwell-like state) [Hills et al 2004]. For this essay, using B.pb and B.nts to sense nearby food seems like a reasonable simplification because the simulation animal is aquatic and aquatic taste is a chemosensory system, similar to a close-range olfaction.

The essay uses a signal when the animal is in a food zone or not in a food zone. The food zone signal inhibits eating or seeking actions when the animal is in a non-appropriate place. The essay uses a signal from B.pb as mentioned above.

In mammals H.l receives input from more sophisticated location systems than a bare chemosensory signal, such as E.sub.d (dorsal subiculum of hippocampus), S.ls (lateral septum, which processes hippocampal output), A.bl (basolateral amygdala, highly connected to hippocampus), S.msh (medial shell striatum receiving large hippocampus input) as well as the bare B.pb as for the simulation. All these areas incorporate more complicated environmental context. When the essays start investigating environmental context, I’ll need to revisit the H.l food zone with more sophisticated input.

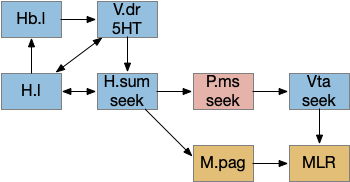

H.sum as driving seek

Fleshing out the drivers of the seek circuit, consider H.sum (supramammillary nucleus, aka retromammillary) and its role in exploring (roaming and seeking). [Ferrell et al 2021] study a subset of H.sum neurons that express tac1 peptide (tachykinin, aka substance-P or neurokinin). These H.sum neurons correlate highly with movement velocity, a second before the action. Since they precede action, they’re upstream in the locomotive path.

H.sum is also involved in wakefulness [Liang et al 2023], [Plaisier et al 2020], motivation [Kesner et al 2021], and specifically food motivation [Le May et al 2019], and is modulated by hunger peptides like GLP-1 [Vogel et al 2016], [López-Ferreras et al 2018].

H.sum also participates in threat avoidance [Escobedo et al 2023], but that circuit is through Poa (preoptic area) and is outside this essay, although it would be interesting if any of the downstream circuitry is shared. H.sum is also well know for its role in hippocampal theta oscillations, novelty [Chen et al 2020], temporal and spatial memory [Cui et al 2013], and social memory, although those are outside the scope of this essay.

The diagram below shows a possible explore-related path of mammalian H.sum via the tac1 neurons.

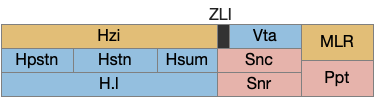

It may be important that H.sum and Vta (ventral tegmental area) are both neighbors and H.sum includes dopamine neurons and those dopamine neurons are sometimes considered an extension of the Vta [Yetnikoff et al 2014].

The following diagram gives an extremely rough idea of the adjacency of these areas. In a smaller primitive pre-vertebrate, these might not only be neighbors but mingled earlier functionality. The diagram includes H.zi (zona incerta) because it’s a neighbor, and also because H.zi is a food-seeking area [Ye et al 2023], but I’m postponing consideration of H.zi to a future essay.

In addition, the rostral part of Vta nearest H.sum is part of p3 in the prosomeric embryonic model, which is a source of hypothalamic cells [Kim et al 2022]. For pre-vertebrates in this essay, then, there might not be a distinct between H.sum and Vta / posterior tuberculum, particularly since the essays are currently focusing on downstream connections, not upstream dopamine to a future striatum. Zebrafish downstream dopamine circuits directly modulate locomotor movement [Ryczko et al 2020], [Reinig et al 2017]. I think it’s reasonable to simplify this circuit for now and consider H.sum as directly projecting to MLR.

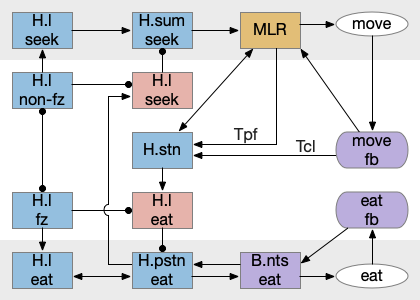

State transition circuit for seek to eat

Putting these ideas together yields something like the diagram below. Like the earlier simplified diagram, horizontal paths drive core seeking and eating behavior, and other circuits manage the state transition. Seeking uses the top path from H.l to H.sum to MLR to B.rs, which produces the final locomotion. Eating uses the bottom path from H.l to H.pstn to B.nts, which controls reflexive eating.

The left contains motivational drivers. The food zone and non food zone systems restrict seeking and eating, only allowing seeking and eating in appropriate locations.

In the center H.stn and its parallel H.stn enforce a smooth transition between seeking and eating, using motor efferent copies to pause transition until active motor stops. The smooth transition creates the illusion of an atomic state transition.

As a diagram note, I’ve used red for the H.l inhibitory neurons that gate seek and eat because they’re playing the same role as Snr neurons. Technically they should be blue, if following normal essay conventions.

Modulation of eating

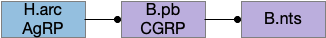

The eating and feeding modulation systems are complicated and overlapping, which is too detailed for this essay, but two part are interesting. First, B.pb tonically inhibits eating with the CGRP peptide to B.nts. To enable eating, H.arc (hypothalamus arcuate) disinhibits B.nts eating by sending AgRP (a hunger peptide) to B.pb [Campos et al 2016].

Although the essays have used the disinhibition pattern before, the pattern has generally ben GABA disinhibition, while this feeding disinhibition uses peptide signaling. As mentioned above, there are many feeding-related peptides that inhibit, excite, and modulate the feeding system without using connection based synapses.

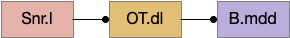

As a parallel, a drinking modulation path goes through the basal ganglia Snr and OT (optic tectum) [Rossi et al 2016]. This path though the basal ganglia and OT coordinates anticipatory licking, while the earlier B.nts path is reflexive eating.

Another drinking path involves S.a (central/striatal amygdala), midbrain, and hindbrain circuits [Zheng et al 2022]. M.dp (deep mesencephalic nucleus) extends licking but doesn’t initiate it. So M.dp might extend eating after tasting. Similarly B.plc extends eating [Gong et al 2020]. S.a sst (somatostatin peptide) neurons promote eating and drinking [Kim et al 2017].

Another path for tasting and eating runs through S.v (ventral striatum). [Sandoval-Rodríguez et al 2023] founds S.v directly controlling feeding using hindbrain taste input to extend eating, and using hindbrain GLP-1 (anti-eating peptide) to inhibit eating. Unlike most striatum circuits, these striatum neurons project directly to the hindbrain motor areas.

Because this essay is already complicated enough, this simulation isn’t covering all of these details. For simplicity, the simulation will use a simple continuation circuit inspired by the central amygdala and postpone other control circuits for later exploration.

The important point for now is that eating modulation uses multiple paths, some controlled through synaptic circuits and others through broadcast motivational peptides. The system is not one or the other, but a messy combination. To model this messiness, the simulation needs to handle both systems.

References

Barbier M, Risold PY. Understanding the Significance of the Hypothalamic Nature of the Subthalamic Nucleus. eNeuro. 2021 Oct 4.

Ben Arous J, Laffont S, Chatenay D. Molecular and sensory basis of a food related two-state behavior in C. elegans. PLoS One. 2009 Oct 23;4(10):e7584.

Campos CA, Bowen AJ, Schwartz MW, Palmiter RD. Parabrachial CGRP Neurons Control Meal Termination. Cell Metab. 2016 May 10;23(5):811-20.

Chen S, He L, Huang AJY, Boehringer R, Robert V, Wintzer ME, Polygalov D, Weitemier AZ, Tao Y, Gu M, Middleton SJ, Namiki K, Hama H, Therreau L, Chevaleyre V, Hioki H, Miyawaki A, Piskorowski RA, McHugh TJ. A hypothalamic novelty signal modulates hippocampal memory. Nature. 2020

Cui Z, Gerfen CR, Young WS 3rd. Hypothalamic and other connections with dorsal CA2 area of the mouse hippocampus. J Comp Neurol. 2013 Jun 1;521(8):1844-66.

Dorfman A, Hills TT, Scharf I. A guide to area-restricted search: a foundational foraging behaviour. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2022 Dec;97(6):2076-2089.

Escobedo Abraham, Holloway Salli-Ann, Votoupal Megan, Cone Aaron L, Skelton Hannah E, Legaria Alex A., Ndiokho Imeh, Floyd Tasheia, Kravitz Alexxai V., Bruchas Michael R., Norris Aaron J. (2023) Glutamatergic Supramammillary Nucleus Neurons Respond to Threatening Stressors and Promote Active Coping eLife 12:RP90972

Farrell JS, Lovett-Barron M, Klein PM, Sparks FT, Gschwind T, Ortiz AL, Ahanonu B, Bradbury S, Terada S, Oijala M, Hwaun E, Dudok B, Szabo G, Schnitzer MJ, Deisseroth K, Losonczy A, Soltesz I. Supramammillary regulation of locomotion and hippocampal activity. Science. 2021 Dec 17;374(6574):1492-1496.

Flavell SW, Pokala N, Macosko EZ, Albrecht DR, Larsch J, and Bargmann CI (2013). Serotonin and the neuropeptide PDF initiate and extend opposing behavioral states in C. elegans. Cell 154, 1023–1035.

Gong R, Xu S, Hermundstad A, Yu Y, Sternson SM. Hindbrain Double-Negative Feedback Mediates Palatability-Guided Food and Water Consumption. Cell. 2020 Sep 17;182(6):1589-1605.e22.

Hills T, Brockie PJ, Maricq AV (2004) Dopamine and glutamate control area-restricted search behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci 24: 1217–1225

Horstick EJ, Bayleyen Y, Sinclair JL, Burgess HA. Search strategy is regulated by somatostatin signaling and deep brain photoreceptors in zebrafish. BMC Biol. 2017 Jan 26;15(1):4.

Isoda M, Hikosaka O. Role for subthalamic nucleus neurons in switching from automatic to controlled eye movement. J Neurosci. 2008 Jul 9;28(28):7209-18.

Jennings JH, Ung RL, Resendez SL, Stamatakis AM, Taylor JG, Huang J, Veleta K, Kantak PA, Aita M, Shilling-Scrivo K, Ramakrishnan C, Deisseroth K, Otte S, Stuber GD. Visualizing hypothalamic network dynamics for appetitive and consummatory behaviors. Cell. 2015 Jan 29;160(3):516-27.

Ji N, Madan GK, Fabre GI, Dayan A, Baker CM, Kramer TS, Nwabudike I, and Flavell SW (2021). A neural circuit for flexible control of persistent behavioral states. eLife 10. 10.7554/eLife.62889.

Kesner AJ, Shin R, Calva CB, Don RF, Junn S, Potter CT, Ramsey LA, Abou-Elnaga AF, Cover CG, Wang DV, Lu H, Yang Y, Ikemoto S. Supramammillary neurons projecting to the septum regulate dopamine and motivation for environmental interaction in mice. Nat Commun. 2021 May 14;12(1):2811.

Kim J, Zhang X, Muralidhar S, LeBlanc SA, Tonegawa S. Basolateral to Central Amygdala Neural Circuits for Appetitive Behaviors. Neuron. 2017 Mar 22;93(6):1464-1479.e5.

Kim DW, Place E, Chinnaiya K, Manning E, Sun C, Dai W, Groves I, Ohyama K, Burbridge S, Placzek M, Blackshaw S. Single-cell analysis of early chick hypothalamic development reveals that hypothalamic cells are induced from prethalamic-like progenitors. Cell Rep. 2022 Jan 18;38(3):110251.

Le May MV, Hume C, Sabatier N, Schéle E, Bake T, Bergström U, Menzies J, Dickson SL. Activation of the rat hypothalamic supramammillary nucleus by food anticipation, food restriction or ghrelin administration. J Neuroendocrinol. 2019 Jul;31(7):e12676.

Liang M, Jian T, Tao J, Wang X, Wang R, Jin W, Chen Q, Yao J, Zhao Z, Yang X, Xiao J, Yang Z, Liao X, Chen X, Wang L, Qin H. Hypothalamic supramammillary neurons that project to the medial septum modulate wakefulness in mice. Commun Biol. 2023 Dec 12;6(1):1255.

López-Ferreras L, Eerola K, Mishra D, Shevchouk OT, Richard JE, Nilsson FH, Hayes MR, Skibicka KP. GLP-1 modulates the supramammillary nucleus-lateral hypothalamic neurocircuit to control ingestive and motivated behavior in a sex divergent manner. Mol Metab. 2019 Feb;20:178-193.

Lovett-Barron M, Andalman AS, Allen WE, Vesuna S, Kauvar I, Burns VM, Deisseroth K. Ancestral Circuits for the Coordinated Modulation of Brain State. Cell. 2017 Nov 30;171(6):1411-1423.e17.

Marques JC, Li M, Schaak D, Robson DN, Li JM. Internal state dynamics shape brainwide activity and foraging behaviour. Nature. 2020 Jan;577(7789):239-243.

Plaisier F, Hume C, Menzies J. Neural connectivity between the hypothalamic supramammillary nucleus and appetite- and motivation-related regions of the rat brain. J Neuroendocrinol. 2020 Feb;32(2):e12829.

Reinig S, Driever W, Arrenberg AB. The Descending Diencephalic Dopamine System Is Tuned to Sensory Stimuli. Curr Biol. 2017 Feb 6;27(3):318-333.

Rossi MA, Basiri ML, Liu Y, Hashikawa Y, Hashikawa K, Fenno LE, Kim YS, Ramakrishnan C, Deisseroth K, Stuber GD. Transcriptional and functional divergence in lateral hypothalamic glutamate neurons projecting to the lateral habenula and ventral tegmental area. Neuron. 2021 Dec 1;109(23):3823-3837.e6.

Ryczko D, Grätsch S, Alpert MH, Cone JJ, Kasemir J, Ruthe A, Beauséjour PA, Auclair F, Roitman MF, Alford S, Dubuc R. Descending Dopaminergic Inputs to Reticulospinal Neurons Promote Locomotor Movements. J Neurosci. 2020 Oct 28;40(44):8478-8490.

Sandoval-Rodríguez R, Parra-Reyes JA, Han W, Rueda-Orozco PE, Perez IO, de Araujo IE, Tellez LA. D1 and D2 neurons in the nucleus accumbens enable positive and negative control over sugar intake in mice. Cell Rep. 2023 Mar 28;42(3):112190.

Sawin ER, Ranganathan R, Horvitz HR (2000) C. elegans locomotory rate is modulated by the environment through a dopaminergic pathway and by experience through a serotonergic pathway. Neuron 26: 619–631

Shah T, Dunning JL, Contet C. At the heart of the interoception network: Influence of the parasubthalamic nucleus on autonomic functions and motivated behaviors. Neuropharmacology. 2022 Feb 15;204:108906.

Vogel H, Wolf S, Rabasa C, Rodriguez-Pacheco F, Babaei CS, Stöber F, Goldschmidt J, DiMarchi RD, Finan B, Tschöp MH, Dickson SL, Schürmann A, Skibicka KP. GLP-1 and estrogen conjugate acts in the supramammillary nucleus to reduce food-reward and body weight. Neuropharmacology. 2016 Nov;110(Pt A):396-406.

Watts AG, Kanoski SE, Sanchez-Watts G, Langhans W. The physiological control of eating: signals, neurons, and networks. Physiol Rev. 2022 Apr 1;102(2):689-813.

Wee CL, Song EY, Johnson RE, Ailani D, Randlett O, Kim JY, Nikitchenko M, Bahl A, Yang CT, Ahrens MB, Kawakami K, Engert F, Kunes S. A bidirectional network for appetite control in larval zebrafish. Elife. 2019 Oct 18;8:e43775.

Ye Q, Nunez J, Zhang X. Zona incerta dopamine neurons encode motivational vigor in food seeking. Sci Adv. 2023 Nov 15;9(46):eadi5326.

Yetnikoff L, Lavezzi HN, Reichard RA, Zahm DS. An update on the connections of the ventral mesencephalic dopaminergic complex. Neuroscience. 2014 Dec 12;282:23-48.

Zheng D, Fu JY, Tang MY, Yu XD, Zhu Y, Shen CJ, Li CY, Xie SZ, Lin S, Luo M, Li XM. A Deep Mesencephalic Nucleus Circuit Regulates Licking Behavior. Neurosci Bull. 2022 Jun;38(6):565-575.