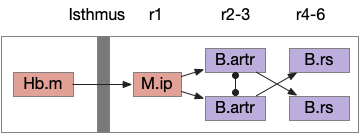

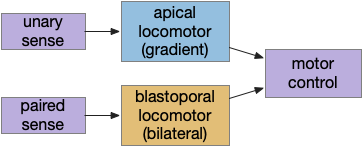

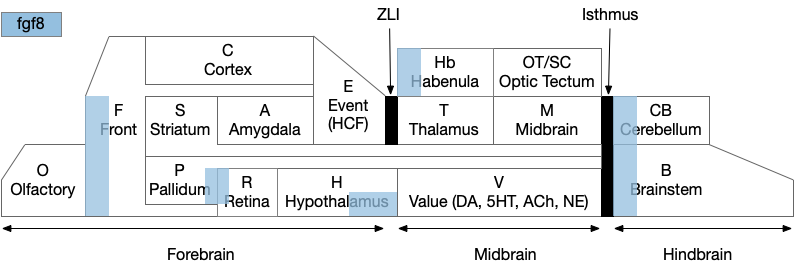

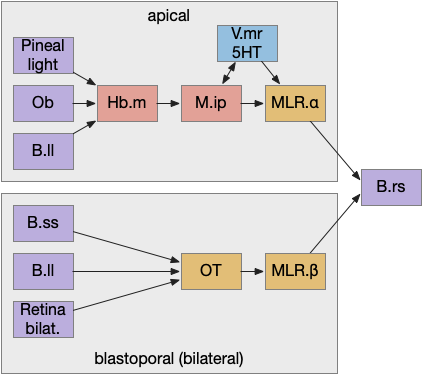

Essay 24, which investigated temporal gradient navigation, raised the question of head direction and navigation. The essay 24 model followed a zebrafish phototaxis experiment by [Chen and Engert 2014] which created a virtual light spot surrounded by darkness. The phototaxis behavior used Hb.m (medial habenula) and B.ip (interpeduncular nucleus) path using 5HT (serotonin) from V.mr (median raphe) as an average integrator [Cheng et al 2016] to generate the gradient without using head direction. Since B.ip receives head direction input [Petrucco et al 2023], essay 25 explores using head direction with the phototaxis gradient.

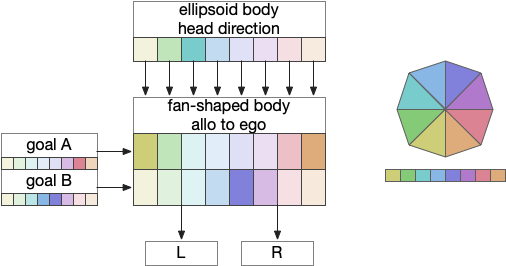

In the fruit fly drosophila, head direction and goal direction combine in the fan-shaped body to produce motor commands toward the goal [Matheson et al 2022]. Since the vertebrate B.ip connectivity with head direction resembles the fan-shaped body, this essay will use it as a model.

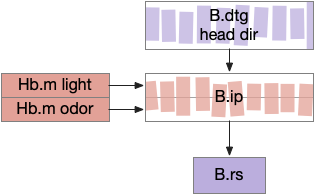

B.ip connectivity

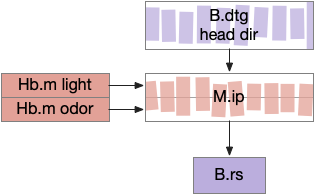

Head direction from B.dtg (dorsal tegmental nucleus of Gudden) and the photo-gradient input from Hb.m would combine in tabular rows and columns in B.ip, if it resembles the fan-shaped body.

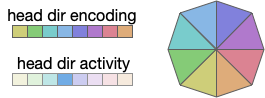

Head direction encoding

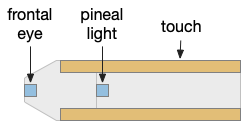

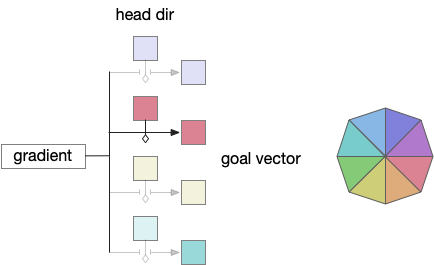

Head direction is necessarily encoded by neurons. Each neuron in the head direction population has a specific direction, and fires when the animal is heading toward the neuron’s preferred direction.

In general, the heading is encoded is an ensemble of neurons, where several neurons around the actual direction fire at different rates (or possibly delayed phases). In the diagram above, the central direction (blue) has a higher activity while neighboring neurons have smaller values [Petrucco et al 2023].

Drosophila uses a coding for its head direction, where the amplitude of the actual direction neuron is close to one and the neurons at orthogonal directions are zero [Westeinde et al 2022]. This sinusoidal encoding enables neuron-friendly transformations and combinations [Touretzky et al 1993] with advantages over neural rate-encoding or phase encoding, particularly in response speed.

Fan-shaped body: allocentric to egocentric

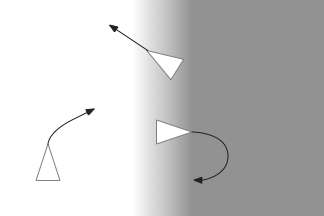

Fruit fly navigation uses its fly-shaped body to combine an allocentric goal direction with the head direction to create motor commands to turn left or right. Egocentric is self-focused and allocentric is other-focused. Allocentric coordinates are animal-independent like North or toward a distant landmark, which egocentric coordinates are relative to the animal, like forward, right or left.

The fan-shaped body has a tabular shape where each column is a head direction and each row is a goal input [Hulse et al 2021]. The fan-shaped body combines the goal vector and the head direction to create motor commands [Westeinde et al 2022].

By shifting the head direction and combining the sinusoidal encodings of the goal vector, the motor output is a turn toward left or right. In drosophila, there’s a third motor command for a U-turn when the goal is behind the fly. Each motor command is carried by a specific neuron: PFL2.L (left), PFL2.R (right), and PFL3 (U-turn).

In drosophila, there are 18 distinct head direction columns and up to 9 goal rows. The fan-shaped body is also used for motivation calculations like sleep, despite sleep not fitting into the strict tabular model shown above. To create the strict organization, the fan-shaped body has 400 distinct neuron types [Hulse et al 2021].

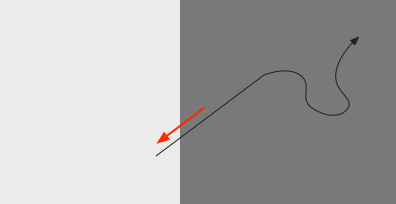

Constructing goal vectors

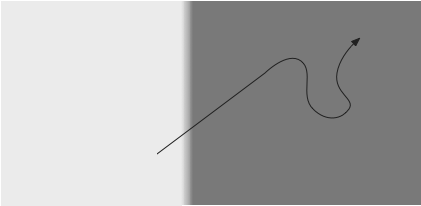

In the phototaxis situation as in essay 24 or [Chen and Engert 2014] the goal vector is constructed from the gradient as the animal enters darkness from light and the head direction at that moment.

As the diagram above suggests, the stored vector isn’t the true direction from light to dark, but only the sample along the animal’s path. The gradient value is then stored in the goal direction cells.

Storing the goal vector requires gating based on head direction. In zebrafish, serotonin accumulators can be gated by actions and used as a short term memory (5s – 20s) [Kawashima et al 2016]. For the essay, head dir gates serotonin accumulation as a replacement for the action gating.

Since V.mr (median raphe) neurons produce consistent tonic oscillations, they are ideal for reading the accumulated value. No additional circuitry for the read is necessary.

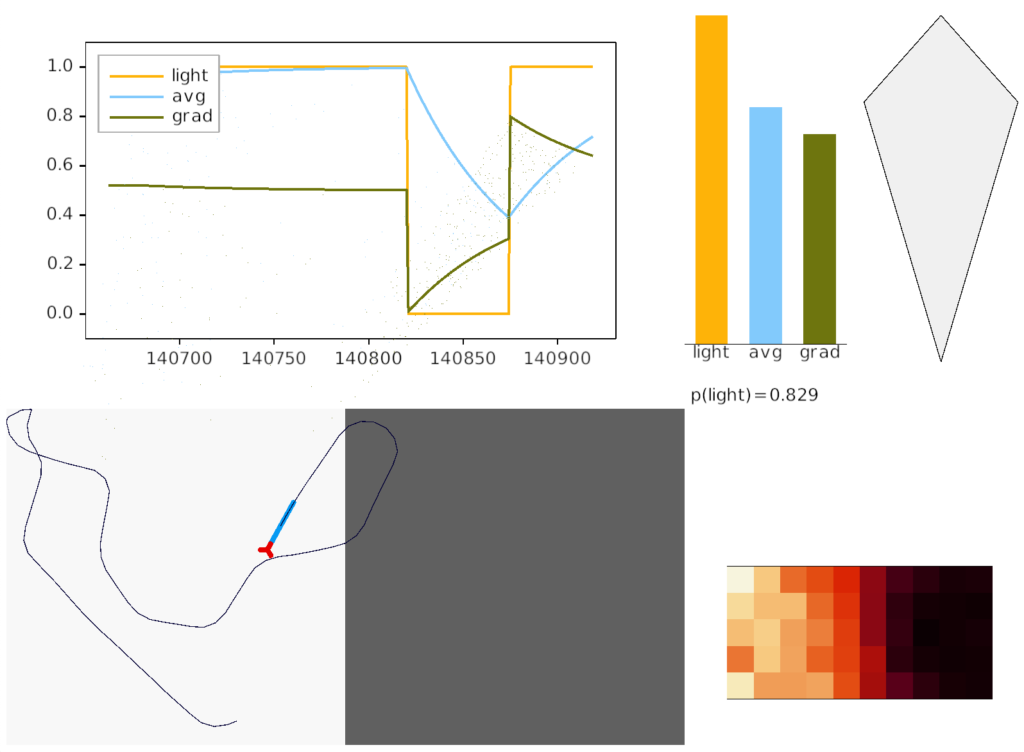

Essay simulation

Because the essay model is a functional level, not a circuit level, it can use a directional vector encoding: a pair of floating-point numbers for direction and gradient for strength.

The simulation also calculated two averages: a short-term average for the goal vector gradient and a long-term average for phototaxis gradient motivation. The goal vector average needs to be shorter to avoid bleed-over from a previous direction.

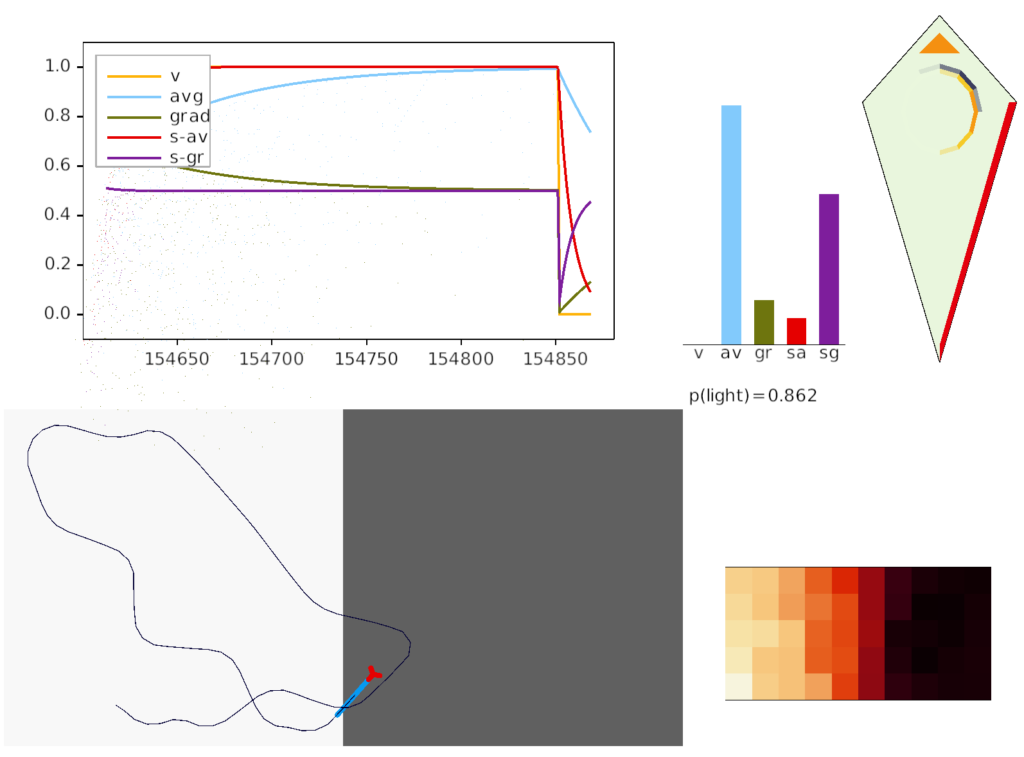

The above screenshot shows the animal’s state when it crosses into darkness. The long-timescale motivational gradient (“gr/grad”) is negative, driving the animal to avoid darkness. The short directional gradient (“sa”) is near zero, avoiding update of the stored goal vector. (Note: gradients are 0.5-centered for graphing consistency.)

The homunculus diamond in the upper right shows the current head direction (black semicircle pointing north-east) and the avoidance goal vector (orange semi-circle pointing east). Since the animal is heading toward the avoidance direction, it has a U-turn motor command (orange triangle at top). In addition, since the goal vector and head direction are near a right angle, right turns are inhibited (red at lower right). Because locomotion remains exploratory and stochastic, inhibits reduce turn probability but don’t force turns.

Discussion

This essay’s model is more speculative even compared to other essays, because I haven’t found any papers reporting in B.ip head direction behavior other than the base existence of head direction afferents [Petrucco et al 2023]. In particular, the drosophila fan-shaped body is not homologous to B.ip because the pre-vertebrate animal amphioxus lacks either structure. Nevertheless, it’s interesting that a goal gradient vector circuit is at least possible and relatively simple.

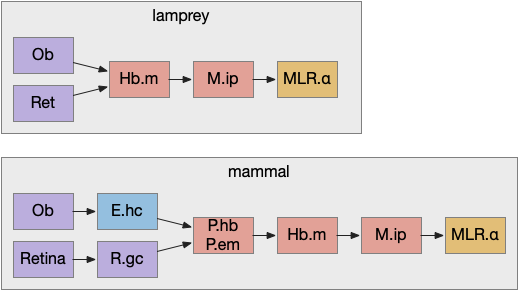

Specifically, the goal vector provides an evolutionary step toward hippocampal (E.hc) object vector cells and grid cells, because those are relatively small enhancements over the goal vector. Without a Bi.ip goal vector system as an intermediary step, hippocampal navigation is too big of an evolutionary step with too many concurrent requirements to be likely.

Note that the hippocampal system is strongly connected with the Hb, B.ip, V.mr, B.dtg system from this essay. E.hc (hippocampus), P.ms (medial septum), Hb (habenula), B.ip (interpeuncular nucleus), V.mr (median raphe), B.dtg (head direction) form a strong connected system together with H.sum (supramammilary/ retromammilary nucleus).

References

Chen X, Engert F. Navigational strategies underlying phototaxis in larval zebrafish. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014 Mar 25;8:39.

Cheng RK, Krishnan S, Jesuthasan S. Activation and inhibition of tph2 serotonergic neurons operate in tandem to influence larval zebrafish preference for light over darkness. Sci Rep. 2016 Feb 12;6:20788.

Hulse, B. K., Haberkern, H., Franconville, R., Turner-Evans, D., Takemura, S. Y., Wolff, T., … & Jayaraman, V. (2021). A connectome of the Drosophila central complex reveals network motifs suitable for flexible navigation and context-dependent action selection. Elife, 10.

Kawashima T, Zwart MF, Yang CT, Mensh BD, Ahrens MB. The Serotonergic System Tracks the Outcomes of Actions to Mediate Short-Term Motor Learning. Cell. 2016 Nov 3;167(4):933-946.e20.

Matheson, A. M., Lanz, A. J., Medina, A. M., Licata, A. M., Currier, T. A., Syed, M. H., & Nagel, K. I. (2022). A neural circuit for wind-guided olfactory navigation. Nature Communications, 13(1), 4613.

Petrucco L, Lavian H, Wu YK, Svara F, Štih V, Portugues R. Neural dynamics and architecture of the heading direction circuit in zebrafish. Nat Neurosci. 2023 May;26(5):765-773.

Touretzky, D. S., Redish, A. D., & Wan, H. S. (1993). Neural representation of space using sinusoidal arrays. Neural Computation, 5(6), 869-884.

Westeinde Elena A., Emily Kellogg, Paul M. Dawson, Jenny Lu, Lydia Hamburg, Benjamin Midler, Shaul Druckmann, Rachel I. Wilson (2022). Transforming a head direction signal into a goal-oriented steering command. bioRxiv 2022.11.10.516039;